The Eurasian Otter in Peninsular India

“The otter (Lutra vulgaris), of which genus I have never been able to distinguish more than one species in the Central Provinces… is found locally in all the main rivers and larger jungle streams. In appearance they exactly resemble the European otter, but are somewhat less heavily coated. A large male weighs 22 lb. Two to five animals are often seen together, but occasionally regular schools are met with. I once counted 22 otters in one pool. When fishing they co-operate and forming a semicircle drive the fish on to a shoal. Their food is not by any means confined to fish, and when the pools shrink in the hot weather I have known them to inhabit an earth on the hill-side and take to jungle hunting like other carnivores. They are by no means helpless on land, and a tame otter possessed by Col. Chapman, I.M.S., used to accompany the ‘bobbery’ pack after jackal. The only cry I have ever heard them utter is a shrill yap.”

A view of the rugged terrain of the Satpuras, with jagged peaks and deep valleys defining this landscape. Photo: Aditya Joshi/WCT

This is how A.A. Dunbar Brander, arguably the most well-known naturalist-officer of the Imperial Forest Service (IFS) to have served the Central Provinces described otters in the forests of this region in his book Wild Animals in Central India (1923). Much water has flown down the jungli rivers of central India since. The forests of Central Provinces that Brander once trod across are now famed wild havens of Madhya Pradesh, the ‘Tiger State’ of India, and eastern Maharashtra.

Eurasian otters are highly nocturnal in their ways and inhabit mountain streams and deep perennial pools. Photo: WCT

The barasingha’s bugling calls still envelop the Banjar valley of Kanha, the rugged hills of Satpura still reverberate under the hooves of hundreds of gaur, the whistles of large packs of dholes continue to echo through forests along the Pench river, and the stately sambar lords over the jungles of Balaghat. A few remaining wild buffaloes still thunder across the Indravati in Gadchiroli and Bastar, while Balu, the sloth bear, gambols pretty much through every forest in this region. The rosetted prince of the forest, the leopard, still moves surreptitiously from the arid forests of Gwalior to the teak forests of Chandrapur, and the king, the tiger, reigns supreme from the ancient forts of Bandhavgarh to the citadels in Melghat. But what about otters? How did they fare in central India in the decades that passed since Brander wrote about them? Well, the answer to this question was disappointing for the longest time, but somewhat expected – we simply did not know!

SATPURA’s WILDS Winters are bitterly cold in the Satpura Tiger Reserve, and it seemed like any other freezing December. The year was 2015. A 12-member Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) team was working with the forest department to undertake a comprehensive camera trap survey of the tiger reserve. Even though Satpura was no stranger to cameratrapping, this year’s exercise would be special. For the first time in the tiger reserve’s history, the entire reserve would be camera trapped. The rugged terrain of Satpuras had made it extremely difficult to survey and explore large parts of the reserve, both for forest department staff and wildlife biologists. This was the first time when even the remotest, unsurveyed portions of the tiger reserve would be brought under the camera’s eye.

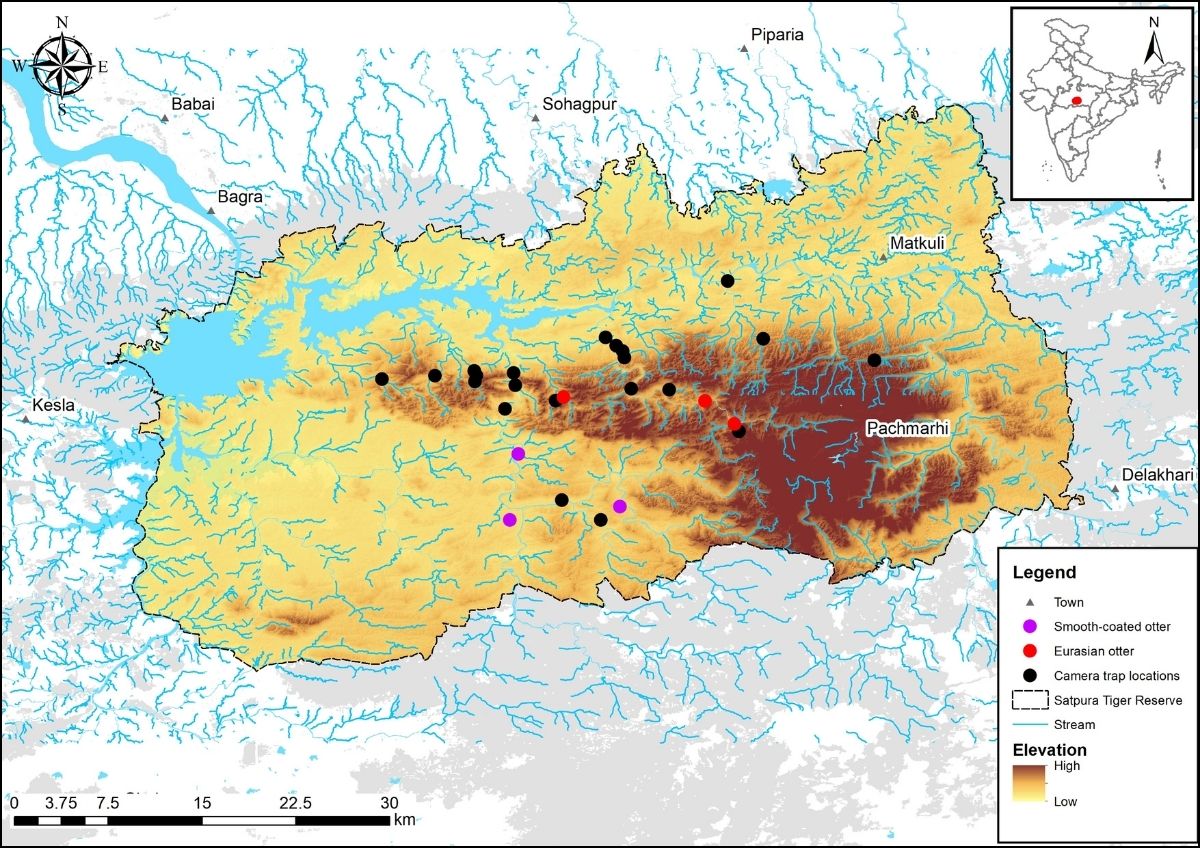

SETTING THE STAGE The entire reserve, comprising its three constituent units – Satpura National Park, Bori Wildlife Sanctuary, and Pachmarhi Wildlife Sanctuary – was divided into two-square-kilometre grids to place camera traps. That was the easy part. The real challenge was to figure out the routes to reach each of these grids.

Aditya Joshi, who now heads the Conservation Research vertical at WCT, led the team of researchers involved in this process. An old Satpura hand, the tiger reserve had been his field site during his Master’s days in 2009. Once the routes had been figured, it was time for field action. Small joint teams of forest staff and WCT researchers began the arduous task of deploying camera traps.

How did otters fare in central India since naturalist-officer of the Imperial Forest Service A.A. Dunbar Brander wrote about them in 1923? Well, the answer for the longest time to this question was disappointing, but somewhat expected – we simply did not know!

“I was assigned a precipitous hilly block in the Kamti range with jagged peaks that lay in the core of the tiger reserve, a block of forest that had never been systematically camera-trapped before,” recalls Joshi.

“It was a punishing uphill trek through some of the most difficult terrain I have ever walked through. Eventually, after nearly 13 km. of huffing and puffing, our team reached this stunning rocky forest stream near the mountain summit. It is difficult to put in words how grand, perhaps even intimidating, this stream bed was – dense forests cloaking either bank and gigantic boulders, almost straight out of a Jurassic movie, strewn haphazardly with clear water gurgling through them. Here, there were small sand bars skirting around these boulders. While inspecting these slivers of sand for animal signs, I noted something remarkable – otter tracks! I was dumbfounded because while I knew of the presence of smoothcoated otters in the Denwa river that snakes through the lower elevations of the reserve, it was odd to find otter signs at such an elevation in a precipitous mountainous stream! Even though the prime purpose of the survey was to assess tiger and leopard populations, out of curiosity, we placed a few additional camera traps here and then moved ahead on our uphill trek,” he shared.

Captain James Forsyth was the first European to systemically survey the flora and fauna of the Satpura ranges in particular, and central India in general. He wrote eloquently about them in his book ‘Highlands of Central India’ published in 1871. Photo: Highlands Of Central India by Captain James Forsyth, 1871

In 2015, for the first time in the Satpura Tiger Reserve’s history, the entire length and breadth of the reserve was camera-trapped. The rugged terrain of the Satpuras made it extremely difficult to survey and explore large parts of the tiger reserve.

A month later, the traps were collected and brought back to the base camp. The team sifted through thousands of images from scores of traps. Incredible images of tigers, leopards, dholes, various ungulates, and elusive nocturnal species appeared across the researchers’ screens. Then, the memory card from the cameras installed across that stream in Kamti range was plugged into the laptop. What the team saw on the screen on that cold January night of 2016 caused their tired eyes to pop in amazement – otters! But not the usual smooth-coated ones. These looked different, and they were! Were they looking at the first ever photographic images of Eurasian otters from Indian territory?

OTTERLY CONFUSING India is home to three otter species – the smooth-coated, the Asian small-clawed, and the Eurasian Lutra lutra. While all are lumped together as the ‘water-cat’ in various Indian languages, there are differences between the three. As S.H. Prater put it, whereas the smooth-coated is “essentially a plains otter”, the Eurasian is “essentially an otter of cold hill and mountain streams and lakes”. It is difficult to tell the two apart from tracks or even casual sightings for the visual differences are rather subtle.

Measuring anywhere between one to 1.4 m., Eurasian otters are slightly smaller than their larger smooth-coated cousins, and can weigh between six and 11 kg. Also known as the European otter, the Eurasian has a broader head compared to the smooth-coated, along with a broad pronounced muzzle, and longer snout that terminates in a zig-zag pattern around the nose. It sports a rather scruffy bedraggled coat, and a cylindrical, gradually tapering tail. Moreover, Eurasian otters are mostly solitary-living, or live in small family groups, while the smooth-coated otters are more gregarious. Which accounts for Dunbar- Brander finding it so difficult to “distinguish more than one species in the Central Provinces” even though he observed that the otters “exactly resemble the European otter”.

Tracing the natural history of the three otter species in India is equally befuddling, primarily owing to endless confusion over their nomenclature among British Indian taxonomists and naturalists. “The specific nomenclature of the…otters…of British India, has been in a state of almost hopeless confusion, hardly any two authors agreeing on the points at issue,” wrote British zoologist R.I. Pocock in his book The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma – Mammalia (1941), before going on to explain his “attempt to unravel the tangle” in which he assigned another set of new names for all the species, adding that “hardly any of the names adopted for the British Indian species are the same as those employed by Jerdon, Anderson and Blanford and the authors who followed them”.

Nonetheless, a study of past literature offers some clues on the historic distribution of Eurasian otters. Among the many names assigned to them, one of the most ‘common’ was ‘common otter’. In fact, the current prevalent name, i.e. Eurasian otter has gained currency only in recent decades. Pocock wrote that “the so-called ‘Common’ Otter (Lutra)…are found only in the Himalayas and to the north of the Ganges and in Southern India…[and]…Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. They are absent over the whole of Central India…Thus, their distribution is discontinuous.” Prater reiterated the same and wrote that “in India, the common otter is found only in Kashmir, the Himalayas, and Assam, and nowhere in the Peninsula except in south India”.

Many remote hill streams of the Satpura Tiger Reserve are marked by gigantic boulders strewn haphazardly with clear water gurgling through them. A team member navigating through them provides a scale to gauge the size of these boulders. Photo: Aditya Joshi/WCT

HIDDEN RECORDS However, I have come across three confirmed written records of the existence of the Eurasian otters in central India, two of which were missed by both Pocock and Prater, while one came in later. In the early 20th Century, Central Provinces produced a remarkable set of district gazetteers, edited by a group of capable Indian Civil Service (ICS) officers. As editors, most of these ICS officers roped in experts from various departments to send in detailed notes on the resources of the concerned district pertaining to their areas of expertise. For forests and wildlife, serving forest officers were engaged. As a result, two of these gazetteers provide irrefutable evidence of the presence of Eurasian otters in Central India.

For the preparation of the District Gazetteer of Jubbulpore (Jabalpur), published in 1909, A.E. Nelson was informed by A.L. Chatterji, the Extra-Assistant Conservator (EAC) of Forests that there were two species of otters found in the streams of his forest – “2 species represent the genus Lutra: – the common otter (Lutra vulgaris) and the smooth Indian otter (Lutra Ellioti)[sic]”.

When the memory card from the cameras installed across that stream in Kamti range was plugged into the laptop, the research team’s tired eyes popped out in amazement. Were they looking at the first ever photographic images of Eurasian otters from Indian territory?

Distribution map of Eurasian and smooth-coated otters in the Satpura Tiger Reserve. Photo: WCT

A view of a hill stream in the higher reaches of the Satpura hills flanked by rocky escarpments with occasional slivers of sand bars.A typical Eurasian otter habitat. Photo: Aditya Joshi/WCT

Similarly, another ICS officer named E.A. De Brett was tasked with preparing the gazetteer for all the princely states of Chhattisgarh. For the princely state of Bastar, his source of information was E.A. Rooke, the Forest Officer of Bastar. Rooke was a name familiar to me, George Schaller’s seminal work The Deer and the Tiger (1967) refers to an unpublished manuscript written by Rooke titled Wild Animals and Birds of Bastar (1908), which was kept in the archives of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), and had been accessed by Schaller. Rooke too informed Brett about the presence of two species of otters in Bastar’s forests , and thus the Gazetteer of Chhattisgarh Feudatory, published in 1906, reads, “Want of space prevents a detailed description of the smaller denizens of the forests. Two sorts of otter (Lutra vulgaris and Lutra Macrodus) [sic] are found.” Lutra macrodus is an obsolete taxonomic name of the smooth-coated otter.

There are other possible records of presence of Eurasian otters (nomenclatured as common or common Indian otter) from Seoni, Chhindwara, Betul, Balaghat, Mandla, Melghat, etc., but since those references don’t explicitly state the presence of two different species, there exists a possibility of them mislabelling smoothcoated otters as Eurasian on account of the “hopeless confusion” over nomenclature that Pocock spoke about.

Finally, the last report of a Eurasian otter from central India comes from a 1978 note sent to the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society by Maruti Chitampalli, the legendary Marathi naturalist-writer and forest officer. Chitampalli was serving as the Sub-Divisional Forest Officer at the Nawegaon National Park (now part of the Nawegaon-Nagzira Tiger Reserve) in Maharashtra’s Gondia (previously part of Bhandara) district. His note titled ‘On the occurrence of the common otter in Maharashtra (Itiadoh Lake- Bhandara District) with some notes on its habits’ described that while he had seen otters in “Nawegaon Bandh, Gandhari and Palandur….and Itiadoh lake”, it was a specimen produced to him by a fisherman from the area that then enabled confirmation of the species as the common Indian otter Lutra lutra by the BNHS. Chitampalli noted that “the Common Indian Otter has not been recorded by Prater (1971 Book of Indian Animals), as occurring in these parts, or for that matter anywhere except in Kashmir and southern India. The smooth-coated Indian Otter (Lutra perspicillata) too has been recorded only once in 1826 within the limits of Maharashtra (1974, Maharashtra State Gazetteer p. 354)”.

Chitampalli too had missed the Eurasian otter records from Jabalpur and Bastar Gazetteers.

India is home to three otter species – the smooth-coated otter, the Asian small-clawed otter, and the Eurasian otter Lutra lutra. Tracing their natural history is befuddling, owing to confusion over their nomenclature among British Indian taxonomists and naturalists.

Ensconced within the larger Satpura hill system, that runs through the wild heart of central India and forms the watershed between the mighty Narmada and Tapti river systems, the Satpura Tiger Reserve is spread over 2,133.307 sq. km. in the Narmadapuram (previously Hoshangabad) district of Madhya Pradesh. The site of India’s first reserved forest (Bori) notified in 1865, a large part of the tiger reserve comprises highlands defined by punishing terrain consisting of a jagged peaks, deep valleys and gorges, escarpments, ravines, waterfalls, streams, and rivulets. Clothed in thick sal and teak forest stretches, with the Pachmarhi plateau being the dividing line for these two species, it is interspersed with some of peninsular India’s best and densest bamboo forests. This rugged terrain of the Satpura, birthing the highest peak in central India, has been its defining feature since eons – blessing it with some of India’s most awe-inspiring vistas that have afforded safe harbour by forming a natural barrier from human incursions for its myriad denizens down the centuries.

RESOUNDING CONFIRMATION “I still get goosebumps thinking about that day,” reminisces Aditya Joshi about those first images of otters from that jungle stream in Kamti range. “I was quite sure that we were seeing the first-ever photographic records of Eurasian otters from India, but we still decided to reach out to experts for confirmation,” he said.

Will Duckworth and Nisarg Prakash, the experts in the IUCN Otter Specialist Group, and Nachiket Kelkar confirmed the identification. Soon, the spectacular discovery was all over the news – the first photographic record of Eurasian otters from India had been obtained from the Satpura Tiger Reserve.

This discovery of the Eurasian otter in central India was a watershed moment in other ways too. It provided fresh impetus to the research on the status of Eurasian otters in India, and soon, photographic evidence began pouring in from other parts of peninsular India. Divya Mudappa et. al. provided the first photographic as well as molecular evidence of their occurrence in the Western Ghats, when an otter crushed by a car on the Valparai plateau (Anamalai hills, Tamil Nadu) on March 16, 2016 was positively identified as a Eurasian otter.

Earlier, old records from the early 20th Century had suggested the presence of Eurasian otters in Coorg, Nilgiris and the Palni hills, but again confusion over nomenclature made it difficult to claim so with certainty. In fact, as far back as 1874, noted British zoologist and ornithologist T.C. Jerdon, in his book The Mammals of India, had suggested that the otter of the Himalaya, which he called the “hill otter”, was the same as the otter in Ceylon, which in turn was the same as the “small otter of the Neelgherries, referred to by some writers in the ‘Bengal Sporting Review’ &c.; by some called the black otter, by others the red one.” However, cotemporary experts, such as biologist Nisarg Prakash of the IUCN Otter Specialist Group, suggest that Jerdon’s reference to the otters of the Nilgiris could also be the smallclawed rather than Eurasian.

Nonetheless, we have known for a while now that the only otter species in Sri Lanka is the Eurasian otter. Thus, Divya et. al. provided photographic evidence to what Jerdon had suggested 150 years ago vis-à-vis the ‘otter of the Himalaya’ and the otter in Ceylon.

Researchers at WCT continued scouting for Eurasian otters in other central Indian forests and soon came across them in the forests of Balaghat in eastern Madhya Pradesh, and thereafter most recently from thePench Tiger Reserve, Maharashtra, which was also a first record of the species for the state. Other researchers confirmed their presence from dead specimens and photographic records across Peninsular India – from Kanha to Coorg (Karnataka), from Bandhavgarh to Bhadra (Karnataka), and from Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary (Kerala) to Chilika (Odisha).

Photographic images of Eurasian otters were finally obtained from Chhattisgarh – from up north in the little-known district of Korba, home to the Hasdeo forests. Incredibly, this photographic evidence from Chhattisgarh was not from camera-traps or dead specimens, rather two Eurasian otters had been rescued and housed in zoos at Bilaspur and Raipur but misidentified as smooth-coated otters all along. Beyond the peninsular, photographic evidence of Eurasian otters was subsequently also recorded from Ladakh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh. As I finish penning this essay, news has come in that the Eurasian otter has been discovered (rescued from an open well, 15 km. south of Ujani Reservoir) in Pune district as well.

With this, the mystery of how Eurasian otters came from the Himalaya to Sri Lanka – what Pocock described as the problem of their “discontinuous” distribution – has finally been solved. They were always there, waiting to be discovered. And for WCT’s field biologists, it all began with a trek in 2015 to that magical stream that murmurs through the mighty Satpura, where otters still swim, scamper and frolic without a care in the world, unaware of what they did to unravel the fascinating story of their kind!

This discovery of the Eurasian otter in central India was a watershed moment in other ways too. It provided fresh impetus to the research on the status of Eurasian otters in India, and soon photographic evidence started pouring in from other parts of peninsular India.

This article was originally published in the December 2024 issue of Sanctuary Asia.

About the Author: Raza Kazmi is a conservationist, wildlife historian, storyteller, and researcher. He is a Conservation Communicator at WCT and writes in both English and Hindi languages. His writings appear in national newspapers, online media houses, magazines and journals, and various edited anthologies. A recipient of the New India Foundation Fellowship for 2021, he is currently writing a book tentatively titled ‘To Whom Does the Forest Belong?: The Fate of Green in the Land of Red’.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.