Rizwan Mithawala breaks down a cutting-edge forest protection mechanism being implemented in central Indian tiger forests.

Webs made by spiders trap unwary insects, bringing an end to their life. Such predation is essential for the functioning of the food web and sustenance of natural ecosystems. But we humans now pose an existential threat to such well-functioning, self-repairing ecosystems.

Many fragile Indian forests sustain, and are sustained, by one of the most charismatic of all mammals on earth, the tiger. How wonderful it would be to provide such forests a protective web, one as strong as spider silk!

At the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT)’s field station in Madhya Pradesh, one such protective web is being cast on the deciduous forests of central India. The web here is of GPS tracks recorded by forest guards, the foot soldiers of conservation, on their daily patrols.

Photo: Anish Andheria

With 50 confirmed deaths in 2016, tiger poaching in India was the highest in 15 years, according to data compiled by the non-profit Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI). The statistics paint a gloomy picture for India’s national animal – 1,147 tigers killed by poachers in the 24-year period of 1994-2017; an average of 47 tigers each year. And that is only the deaths that were reported.

The surge in the international demand for wild animals and their parts has brought more species under threat than ever before – the number rose from 400 in 2014 to 465 in 2016. The same period saw a 52 per cent increase in poaching and other wildlife crimes, according to a report titled State of India’s Environment 2017: In Figures published by the Centre for Science and Environment.

To fight ever-evolving threats of such magnitude, it is imperative that protection mechanisms be robust and pervade all areas that harbour wildlife. On-ground protection of forests and wildlife has two core components – patrolling and intelligence gathering. In the implementation of these two, the Forest Departments have to adapt to, and be one step ahead of, the rapidly-changing modus operandi of wildlife criminals. Technological advances have now made it possible to carry out patrolling and intelligence gathering with a degree of precision and effectiveness that was difficult to achieve a few years ago.

The launch of Project Tiger in 1973, which led to the formation of India’s first nine tiger reserves, also paved the way for construction of patrolling/anti-poaching camps to facilitate year-round vigilance. Patrolling was considered integral to protection and conservation of wildlife; and the responsibility of securing these reserves lay on the shoulders of forest guards, foresters and watchers. Down the years, problems such as discrepancies in the average area to be covered by each patrolling camp, and lack of manpower, training and equipment have plagued these protection mechanisms.

For decades, patrolling was undertaken as a routine exercise, without much attention to analysis of the data collected. At every patrolling camp, guards would enter detailed information about their daily patrols in lengthy, fifty-two column registers; but those huge data sets were never analysed to draw insights for improved protection. The registers would be sent to senior officers, but the guards never received any feedback. The information was seldom compared across periods or between ranges. Not surprisingly, a 2006 report from the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India attributed several tiger poaching cases to “lack of intelligence networking and monitoring failure at the field level.”

In 2010, the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) along with the Wildlife Institute of India, launched MSTrIPES. Short for Monitoring System for Tigers – Intensive Protection and Ecological Status, this vital tool is a patrol-based wildlife monitoring GIS database, designed to assist wildlife protection, monitoring, and management of Protected Areas. Under MSTrIPES protocols, forest guards are expected to patrol their beats and record their tracks using a GPS, in addition to recording observations in site-specific data sheets.

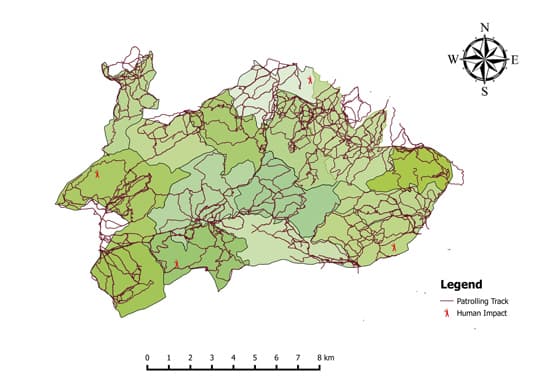

GPS-based patrolling helps in mapping patrol routes and maintaining a spatial database of patrol tracks. When these tracks are analysed through geographic information systems (GIS), a wealth of information on spatial coverage and intensity of patrols emerges. Patrol maps, along with observations recorded by guards, help the management analyse trends and patterns to improve future protection efforts.

Photo Courtesy: Wildlife Conservation Trust

IMPLEMENTING A SOPHISTICATED PROTECTION SYSTEM

In the years that followed the launch of MSTrIPES, very few tiger reserves were able to implement the system. To enable wider acceptance of this cutting-edge protection mechanism, WCT has been working with six tiger reserves and one wildlife sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. The Law Enforcement and Monitoring (LEM) division of WCT works in collaboration with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), the NTCA, and state Forest Departments to make patrolling more systematic and tactical.

Patrolling data, if analysed and interpreted correctly over long periods, can reveal tremendous insights to Field Directors who have a tough time protecting parks that have porous boundaries and high human densities in the buffer zones. Conflict, fuelwood collection and other pressures on India’s parks are only going to increase in future. The need is to implement MSTrIPES in all tiger reserves as it will help identify shortcomings in patrolling efforts in real time. Corrective actions can then be taken before it’s too late.

The LEM division currently facilitates the implementation of MSTrIPES in the Pench and Satpura Tiger Reserves in Madhya Pradesh; and the Pench, Bor, Navegaon-Nagzira and Melghat Tiger Reserves and the Umred-Pauni-Karhandla Wildlife Sanctuary in Maharashtra. Additionally, implementation in other PAs is facilitated when requested. The LEM division analyses around 8,000 km. of foot patrols and resulting observations per week; and has analysed over 12 lakh km. of patrol efforts so far.

The process involves forest guards submitting their GPS devices and site-specific data sheets at an MSTrIPES field office. The weekly patrols recorded by each guard are overlaid on a map of their respective beats (several beats make up a range; and several ranges make up the tiger reserve). As the tracks are laid over beat and range maps, a ‘web’ of patrols over the tiger reserve emerges.

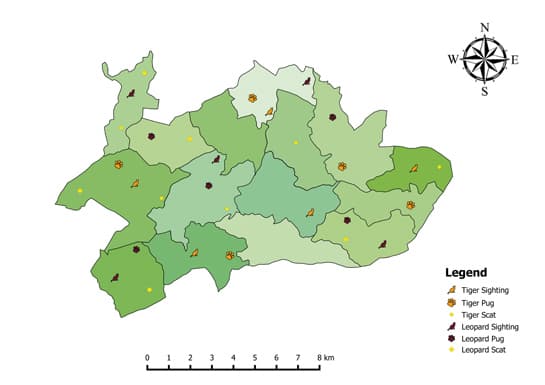

Also plotted on the map are observations submitted by guards. These include human activity (all human activities, other than tourism on permitted forest routes, are considered illegal in tiger reserve cores); animal sightings; animal signs such as calls, pugmarks, scats and scrape marks; animal mortalities and injuries. Such detailed maps are submitted to the respective Range Forest Officers weekly, and bi-weekly to the Field Director.

Photo Courtesy: Wildlife Conservation Trust

HOW MSTrIPES IS SECURING INDIA’S TIGER RESERVES

A patrol-intensity map makes a range-wise comparison and such an analysis not only reveals which ranges have surpassed their targets or are lagging behind, but with the help of precise mapping, also throws light on the reasons for poor or no patrolling in certain areas. The reasons could be as varied as presence of villages in the buffer zones, submergence during the monsoon, exceptionally steep terrain or impenetrable lantana thickets.

Except when faced by such impediments, guards are expected to cover the maximum area of their beat. A map-based analysis helps evaluate this aspect of patrolling. The coverage map may reveal that although guards have met the patrolling target in terms of kilometres, they are patrolling the same route every day. Thick GPS tracks on one route and the absence of tracks in other directions show that patrols are not spread across the entire beat area. Although sensitive areas identified in a beat may require frequent visits by a guard, leaving out other areas can have serious implications on the protection of the beat.

Another intensity map not just ensures protection of wildlife but can also help prevent conflict. Direct and indirect tiger sightings are plotted on the map and compared across months to understand the presence and movement of tigers. If a tiger moves towards a village, appropriate measures can be taken to manage the interface between the tiger and humans.

To prevent poaching and other illegal activities, it is important that guards patrol their beats at random times. Set time-patterns can easily be exploited by criminals. To prevent that, the start and end times of patrols are analysed. This helps the senior forest officials take corrective measures to ensure that patrolling time is as unpredictable as possible.

“Before the implementation of MSTrIPES, there was insufficient monitoring of the guards’ patrolling efforts; we were unable to evaluate their performance as there was no reliable mechanism,” says M. Srinivasa Reddy, Field Director of the Melghat Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra. ”MSTrIPES has helped a great deal in the monitoring, reviewing and planning of patrols… now we get detailed information about which areas are well covered by patrols and which areas require more patrolling. Looking at insights from patrol-time analysis, we also instruct our guards to change their patrol timings regularly.”

Subhoranjan Sen, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (APCCF), Madhya Pradesh Forest Department adds, “We are now able to monitor patrol efforts more intensively and effectively; this includes not just the area patrolled but also the time of the day and the amount of time spent patrolling.”

MSTrIPES also helps guards to improve the effectiveness of their own patrols. There is also another benefit from the proof of their presence in a particular area. If an offence takes place in an area of a guard’s beat while he or she is patrolling elsewhere, there is proof that they have not violated their duties.

However, as wildlife crime figures show, all is not well when it comes to protection inside tiger reserves. Even after the implementation of MSTrIPES, human activities are often overlooked during patrols. Another problem is the low motivation levels of guards. “Over the past couple of decades, several NGOs and government agencies have been working on building capacities of frontline forest staff by imparting training, funds, equipment and insurance. It is now time to turn the attention on the mid-level forest staff to enable them to be better leaders and team-managers,” says Prasenjeet Navgire, head of WCT’s LEM division.

Without a shadow of doubt, technology has added strength to wildlife protection. But we undoubtedly still need stronger planning and implementation on the ground.

To ensure the stability of tiger populations, it is essential that the web of patrols over India’s tiger forests is never weakened. Patrolling must adapt to the changing needs, based on the intelligence gathering. Nearly 30 per cent of India’s tigers live outside the Protected Area network and it is critical that these areas be protected as well.

Map Courtesy: Wildlife Conservation Trust

WCT’s MSTrIPES Training to Frontline Forest Staff

In addition to analysing patrolling data and providing insights to the Field Directors, the LEM division also trains frontline forest staff in patrolling in accordance with MSTrIPES protocols. Guards are trained in the use of patrolling tools such as the GPS, site specific data-sheets, and the MSTrIPES software. During mock patrols, guards are trained to record tracks and waypoints – the latter being the coordinates of a stopping point where an observation is recorded – on the GPS. With the help of photographs of scenarios, objects indicating human presence, and animal signs that are likely to be encountered during patrols, they are trained to make detailed observations and record them on data-sheets. Patrol maps, graphs and other forms of analyses, in addition to their weekly patrol targets in kilometres, are explained to guards, the understanding of which helps them patrol efficiently. The cameras were programmed to take photographs every two minutes after the animals triggered the camera-trap. The number of fruit remaining in the photos across this time-delay sequence (four photographs in eight minutes) were compared to identify fruit eaters from casual visitors.

Map Courtesy: Wildlife Conservation Trust

First published in: Sanctuary Asia, Vol. XXXVIII No. 8, August 2018.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the Author: Rizwan Mithawala is a Conservation Writer with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Related Links

- One Health

- Conservation Strategy

- Reinforcing Forest Protection

- 22 amazing tiger facts – LetsTalkTigers

- Illegal Wildlife Trade: The Need to Look Within

- Quadripartite Association