“Bambb! Bambb! Bambb!” The alliterative sound blares from a trumpet-shaped loudspeaker tied to a bicycle, and fills the evening air around the 400 household Lohara village in the Chandrapur district of Maharashtra. As twilight falls, men assemble at the office of the sarpanch, where the idea of the bambb, an energy-efficient water heater, is presented by Rushikesh Chavan, who leads the Conservation Behaviour team at the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT). Together with the Conservation Research, Livelihoods and Education teams at WCT, efforts are being made to reduce forest degradation and mitigate human-wildlife conflict, in the Bramhapuri Forest Division in Chandrapur. Interventions consider the social, psychological and economic factors that drive the extraction of forest resources and the use of firewood. The water heater is being promoted as an alternative to the traditional firewood-fuelled chulha that is used in every household here to heat water.

Firewood collection is a threat not just to wildlife habitats, but also to the water and ecological security of people. Photo: Ishan Sharma

If the water heater replaces firewood by 70-80 per cent, people may not find it necessary to go to the forest. And even if they do, it would amount to just 20 per cent of the firewood that they extract now,” says Rushikesh Chavan, head of Conservation Behaviour at WCT.

The bambb consumes just one third of the firewood consumed by the chulha to heat the same quantity of water, and can even be fuelled by the woody stems of the toor dal crop that is widely cultivated across the region, eliminating the need to collect firewood. WCT is promoting the use of this water heater by offering it to about a thousand households at one-fourth of the cost, in an effort to understand if it can reduce firewood collection, thereby slowing down the degradation of the forests that surround these villages. If the model proves successful, it can be suggested as an intervention to policy makers. “If the water heater replaces firewood by 70-80 per cent, people may not find it necessary to go to the forest. And even if they do, it would amount to just 20 per cent of the firewood that they extract now,” says Chavan. “Fewer visits to the forest will also mean less negative interaction between humans and wildlife.”

ABOVE LEFT The bambb consumes just one-third of the firewood consumed by the chulha to heat the same quantity of water, and can even be fuelled by the woody stems of the toor dal crop. Photo: Prathamesh Shirsat. ABOVE RIGHT Firewood burning adversely affects the health of women and children. An alternative like the bambb, if adopted, can reduce health risks. Photo: Tamanna Ahmed.

Over the last four years, systematic monitoring of wildlife through camera traps (see page 46 for the ethical questions behind use of camera traps) has revealed a wealth of information about this multi-use landscape. A leopard carrying a monkey by the neck, a tiger with a pangolin in its jaws, a hyena dragging a young domestic goat – these are just some of the images captured by camera traps that also record collection of mahua flowers; collection of firewood by headloads, cycles and motorcycles; and other human activities that indicate the pace of degradation, and the possibility of human-carnivore conflict.

Why is Bramhapuri so important?

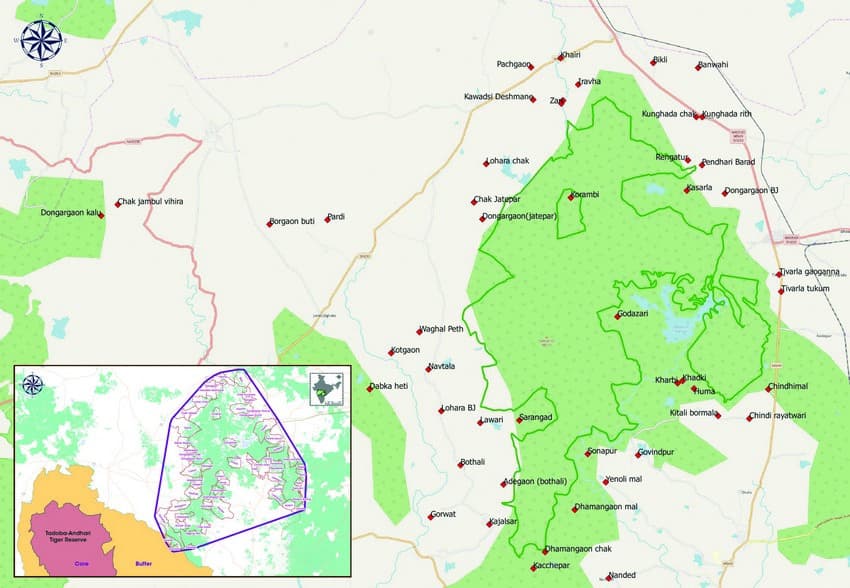

But why concentrate conservation efforts in this area? Contiguous with Maharashtra’s finest tiger bearing Protected Area (PA), the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve, the Bramhapuri Forest Division consists of around 1,100 sq. km. of forest, interspersed with as many as 608 villages. It supports a sizeable population of around 40 resident adult tigers that live cheek by jowl with humans in densities comparable to those of the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve. Tiger movement between Bramhapuri and Tadoba is so frequent that conservation biologists treat both populations as one.

Map showing VSTF villages around the Ghodazari Wildlife Sanctuary in Bramhapuri. The Bramhapuri Forest Division is contiguous with the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve.

After over four years of monitoring wildlife and assessing tiger populations using camera traps in the Greater Tadoba Landscape, comparing satellite imagery from 1970 to the present day to understand land use and land cover change and degradation of forests, mapping the locations of forest fires, and assessing human pressure on forests, WCT’s multi-disciplinary researchers concluded that Bramhapuri was one of the most important forest blocks outside the PA network in India, that would require a multi-pronged approach to make the upliftment of human life and conservation of forests mutually beneficial.

In January 2017, when the Maharashtra government launched its Village Social Transformation Foundation (VSTF) with the aim of developing 1,000 model villages across Maharashtra through a public-private partnership, WCT, as one of the lead partners for the project, suggested a cluster of 49 villages in Bramhapuri, which border the newly declared Ghodazari Wildlife Sanctuary. Under the VSTF model, a Chief Minister’s Rural Development Fellow (RDF) is appointed at each Gram Panchayat. The Fellows live in the villages, understand the needs of the people, prepare village development plans, and ensure the implementation, completion and convergence of various public welfare schemes of the government, to ensure holistic development of the area. Water conservation and storage, sanitation, the nutrition and health needs of women and children, and helping villagers build homes, are just some of the focus areas. WCT assists the RDFs wherever possible, and in addition, studies the interaction between people and wildlife, and suggests corrective measures so as to reduce negative interactions between the two.

Conflict Mitigation

Field biologists install a GSM-enabled camera trap on a forest trail that leads to a village. Photo: Rutuja Dhamale

“No one had the courage to enter the rice fields,” says Sooraj, a resident of the Khadki village, which is among the 49 VSTF villages in Bramhapuri. He is referring to October 2018, when a leopard had wreaked chaos in the otherwise slow-paced lives of the Tadoba villagers. It stayed in and around the village for a month, picking up pet dogs, chickens and goats. GSM-enabled camera traps strategically deployed along the periphery of the village by WCT’s field biologists helped monitor every move of the leopard in real time, and alerts helped avert conflict. GSM-enabled cameras work 24/7 on locations where villages abut forests, as part of WCT’s carnivore alert system in Bramhapuri. “We download the images on a dedicated android phone, and inform the Forest Department if the animal photo-captured is a carnivore and is seen moving towards the village or agricultural field. The Forest Department then sends an alert to the respective village, and takes the appropriate action to avert any human-wildlife interaction,” says Vikrant Wankhade, who leads the carnivore alert programme.

In each of the locations where the ‘foxlights’ have been deployed so far, farmers have reported that raids by herbivores have reduced to a considerable extent. Photo: Prathamesh Shirsat.

Another aspect of conflict mitigation is the installation of solar powered ‘foxlights’ on the periphery of agricultural fields to deter herbivores, including wild pigs, sambar, chital, nilgai and gaur, that raid crops, inflicting immense losses on an already marginalised community dependent on rain-fed agriculture. These lights have nine LED bulbs of different colours that blink randomly to deter herbivores. Where the lights have been deployed, farmers reported that herbivore raids have reduced considerably.

After hanging a glass bottle and an iron nail at the boundary of his paddy field, and a wind chime that he hopes will deter wild herbivores, a farmer stares at the tracks of wild pigs in his lush green paddy. Understanding such anguish is vital to working on conservation issues. “Happy people are a prerequisite for long-term conservation gains,” emphasises WCT President Dr. Anish Andheria. “Working closely with the government at multiple levels, we seek to improve the quality of their lives by sharing efficient farming methods and alternative livelihoods that do not leave them at the mercy of erratic weather, and help them become more climate resilient. Having established that we are genuinely putting their most vital needs first, we would be better placed to talk to them about how tigers, healthy forests, and healthy river systems are linked to agricultural productivity and overall ecological security.”

Students participate in an interactive environment class in a Zilla Parishad school in Chandrapur. Photo: Rizwan Mithawala

In a classroom inside a Zilla Parishad upper primary school in one of the VSTF villages, students, in teams of five, draw their ideal village. The activity is part of WCT’s environment education programme, which is at a nascent stage. The village is close to the forest; yet the forest does not appear in most of the drawings. But there are little silver linings; they are quick to name their favourite animals – sasa, harin, wagh (hare, deer, tiger)! In the coming months, they will learn about the food chain, and all the organisms that play their part in it. They will also learn about the causes of human-animal interactions, and the safest responses in such situations. Once they learn, they will spread the learning. It’s a long road ahead for the educators, but it’s worth all the sweat under Chandrapur’s relentless sun.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the Author: Rizwan Mithawala is a Conservation Writer with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Related Links

- Camera Trap – Means of ‘Counting’ progress

- A Thousand Voices from the Field

- Wildlife Population Estimation

- Otters In Tiger Country

- Poaching and trade of jackals rampant: Study