My fascination for the most unlikely associations in nature continues. Upon digging deeper into the reasons and causes behind various natural phenomena, highly interesting linkages between unexpected entities emerge, reasserting the deep interconnectedness within nature’s design. In the previous and the first chapter of ‘Weird Connections’, we touched upon four little-known interconnections in nature which unbeknownst to most, govern some important aspects of life on Earth such as climate regulation, inter-continental exchange of minerals and nutrients, tilting of the Earth’s axis accentuated due to melting ice and excessive extraction of groundwater, and spread of diseases linked to species extinction!

Let’s explore some more fascinating, yet weird connections in nature!

Of Warming Indian Ocean & Desert Locusts

Early 2020 saw East African countries stave off particularly severe bouts of locust infestations. So severe were the locust outbreaks that the food security and livelihoods of millions of people in Africa and Asia were affected. Hundreds of millions of desert locusts, in swarms as big as New York City, descended on farmlands in countries such as Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia destroying tonnes of crops in matter of hours and days. Though, desert locust plague isn’t a new phenomenon in this part of the world, the deadly outbreak was different for many reasons. The locust plague of 2020 has been attributed to man-made climate change and its genesis has been traced back to two rare and powerful cyclonic events that occurred in 2018 in the Indian Ocean that caused the weather in the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa to become much wetter than normal. In May 2018, a tropical storm Cyclone Mekunu hit the Arabian Peninsula triggering heavy rainfall in an otherwise arid and dry desert, leading to the formation of ephemeral desert lakes in the region. Then in October 2018, another powerful storm Cyclone Luban made landfall in the Arabian Peninsula. The exceptional cyclone season created prolonged favourable conditions for locust breeding. Waves of desert locusts migrated from Yemen to East Africa riding on the winds perpetuated by yet another tropical storm called Cyclone Pawan that formed in December 2019. It is estimated that the Horn of Africa received up to 400 percent more rain than usual between October and December 2019. The wet conditions sustained long enough to allow for about three generations of desert locusts to breed and disperse. The locust swarms having originated in the Arabian Peninsula soon reached South Asia by mid 2020, forcing countries like Pakistan and India to declare emergencies.

Rub’ al-Khali desert in the Arabian Peninsula. To the left is the photograph taken on May 13, 2018, showing normal dry conditions. To the right is the photograph taken on May 29, 2018, depicting the ‘desert lakes’, formed due to intense rainfall triggered by the tropical cyclone Mekunu, which facilitated locust breeding. Photo credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey

A mating pair of ‘gregarious’ desert locust individuals. Photo credit: Adam Matan/Public Domain

So what caused these tropical storms in the first place? It was an oceanic phenomenon called the Indian Ocean Dipole, an ocean temperature gradient that has grown stronger over the last few years due to rising sea surface temperatures that can be attributed to a grievously warming climate. The desert locusts, like other locust species, which are essentially a type of short-horned grasshoppers, undergo a dramatic transformation under the right conditions such as a cooler, greener, wetter environment, and feed and breed profusely. They go from a solitary state to a ‘gregarious’ state in which they turn social and can come together in their billions. And coming together en masse, somehow causes their brains to undergo biological changes, including spike in serotonin levels and increase in brain size! This further triggers stark behavioural and physical changes in the ‘gregarious’ locust individuals. They now take on a bright yellow hue advertising their toxicity to predators, and their legs grow discernibly shorter. Desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria), in particular, is known to cause most economic damage and locust plagues demand major human interventions to bring them under control.

Shortened Life Span of Fig Wasps Can Topple Tropical Forest Ecosystems!

The ubiquitous and life-giving fig trees, all 850 Ficus species of them, depend on a single family (Agaonidae) of tiny pollinators, the fig wasps, to pollinate them. In turn, the life cycle of the fig wasp dramatically begins and ends with a fig. These obligate mutualists have woven an evolutionary saga so fascinating and exerted a biological force so powerful, that they have shaped the tropical forest ecosystems into the biodiverse and rich treasure troves of species that we know them to be.

A female Agaonid wasp, recently emerged from the receptacle (fruiting body) of Ficus sycomorus tree. Photo credit: Alandmanson / Public Domain

Several frugivores such as the Rufous-necked Hornbill largely depend on the figs for food. Photo credit: Shashank Dalvi

Sadly, yet interestingly, human-induced global warming seems to be running a fatal interference in this delicate, ancient relationship between the fig trees and fig wasps. In the last few years, biologists have uncovered a disturbing trend in which the only fig tree pollinators, the fig wasps, are proving to be especially vulnerable to rising temperatures. Several species of fig wasps, it is found, are showing lesser and lesser thermal tolerance to the fast-escalating temperatures across their range in the equatorial tropics. The warming temperatures are playing havoc with their cellular machinery at the molecular level. Result? Shortened life-spans! For these already very short-lived insects, every hour counts. So, their life duration getting cut short even by a few hours, could prove to be devastating not only for the fig wasps, but also their hosts, the fig trees, tipping the scales against their mutualistic connection. The female fig wasps will now have lesser time on their hands to locate receptive figs to nest in and pollinate the fig trees. Several species of fig wasps, it is known, travel long distances, sometimes tens of kilometers in their quest to find host trees. But, shortened life spans will cut short this quest and render their life cycles broken and incomplete. Fig wasp populations will crash, and perhaps have started to already. There, eventually, won’t be enough of them to offer their pollination services, which will lead to decline in fig tree populations.

Here is the thing about fig trees. They are considered to be ecologically, and even culturally, the most important group of plants in the world. Without them an ecological collapse of the colossal kind will ensue. The likes of the Indian banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis), sacred fig tree (Ficus religiosa), cluster fig tree (Ficus glomerata), Sycamore fig tree (Ficus sycomorus) among others, sustain thousands of species of birds, mammals, reptiles, and insects, and have been sustaining them and their ancestors, including ours, for millions of years. Several frugivores such as the hornbills and several species of bats, largely depend on the figs for food. Many forest ecosystems revolve around fig trees as a critical food source.

Unlocking the answers to the Earth and Moon’s gravitational interplay through coral fossils!

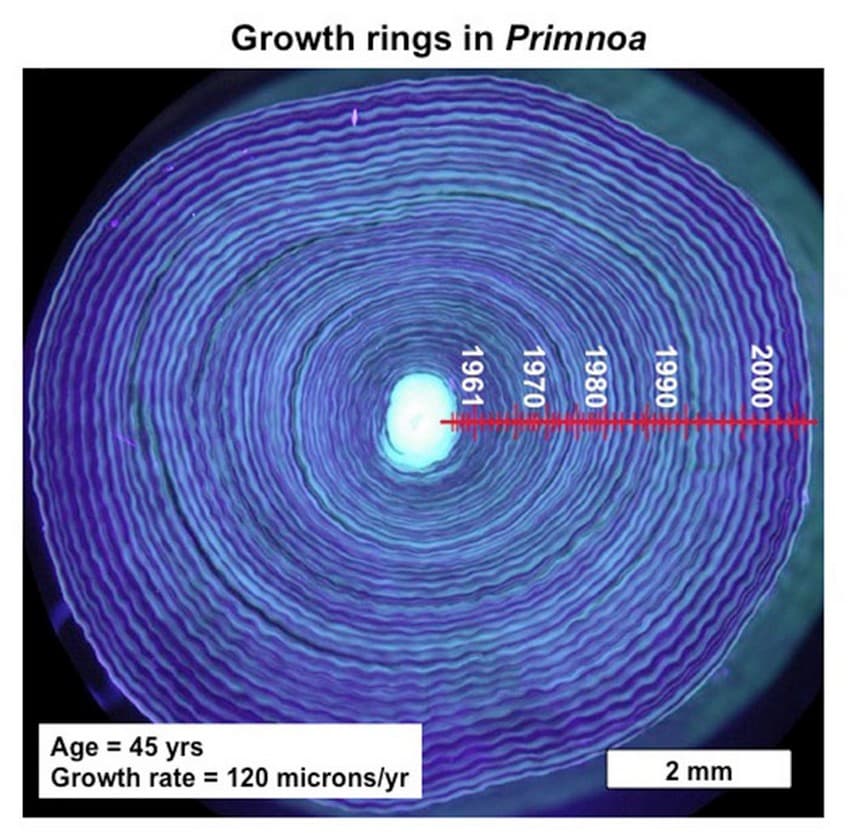

Did you know that the moon was once much closer to the Earth than it is now, and that this allowed it to exert a stronger gravitational pull on the Earth making it spin faster, thus resulting in shorter days? Curiously, the hard evidence that proves this lies in the coral fossils! Corals and sponges have been around in the oceans since about 400 million years ago. Each coral in a coral colony, adds a thin layer of calcium carbonate every day as it grows, without fail. This forms a visible ring marking each day of the year, and each year of its growth is sealed within a distinct band. A cross section of a present day coral will reveal clear bands depicting the number of years, and each band comprising 365 growth rings, which tells us the age of the coral, much like tree rings do.

Ultraviolet light illuminates the growth rings in a cross section of a 44-year-old deep-sea coral (Primnoa resedaeformis). Image credit: Owen Sherwood/NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research/ https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/13midatlantic/logs/may11/may11.html

Astrophysicists, upon observing cross sections of some of the coral fossils from 380 million years ago, counted 410 growth rings within every distinct band. Upon doing the math, it can be concluded that each day was 21 hours long back then. Extrapolating this information with other scientific observations and calculations, we know now that going further back, nearly 3.5 billion years, on a relatively young Earth, the days were just about 6 hours long! This was because the recently formed moon was only about 64,000 km. away from the Earth. Today, the moon sits about 350,600 km. from the Earth. The sun’s gravitational pull, even today, continues to pull the moon further away from our planet, at the rate of nearly 3.6 cm. per year!

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

- Man’s best friend, wildlife’s NEW foe!

- Quadripartite Association

- Manipulative Frankensteins

- Asia’s Dhole Populations At Risk Of Extinction