Untapping Environmental DNA’s Unbridled Potential in Conservation

A cup of water or handful of soil carries within it enticing evidence of life, past and present, in a larger ecosystem. This isn’t some far-fetched or a romanticised claim. It is a relatively new, established biological method of studying biodiversity using the genetic traces that organisms leave behind in the form of DNA in hairs, skin, faeces, saliva, and decaying matter. Such DNA of different species found in the environmental samples like water, soil, snow, and even air is called Environmental DNA or eDNA. The famous Locard’s Exchange Principle observed in forensics – ‘every contact leaves a trace’ – applies well to this growing branch of molecular ecology too, that is picking up fast as an invaluable conservation tool in recent times.

Image by Furiosa-L from Pixabay

Why Environmental DNA?

The planet is home to approximately 9 million species, most of which are still unknown to or undescribed by science. Monitoring this vast and diverse plethora of biodiversity across land and water, and understanding their distribution and populations is extremely difficult, but is just as necessary to aid in meaningful conservation efforts. Especially, in this present day and age of rapid biodiversity loss, traditional methods of biodiversity monitoring are falling short.

Traditional scientific methods such as camera trapping and physical surveys that involve massive, invasive, and expensive undertakings to physically capture, count and/or record individual organisms have their limitations. There is a lot that goes unseen and unnoticed. It is near impossible to monitor and record species’ presence and abundance in its entirety. But, as the use and understanding of eDNA increases, it is becoming more and more clear that eDNA can prove to be a highly accurate biomonitoring tool, that simultaneously allows a bird’s eye view of the species and ecology of an environment as well as closer look at individual species, macro and micro. All this without even having to come across a specimen. The traces that organisms leave behind, even in microscopic amounts, in the form of DNA behold precious information, revealing a more complete picture of an area. And DNA, mercifully, is everywhere. Combined with traditional surveys, eDNA tools can potentially result in more innovative, productive, and efficient ways to study the ecology and species in an environment.

A graphic overview of the species identification process using DNA fragments of organisms through a process known as DNA barcoding. Credit: LarissaFruehe/Wikimedia Commons

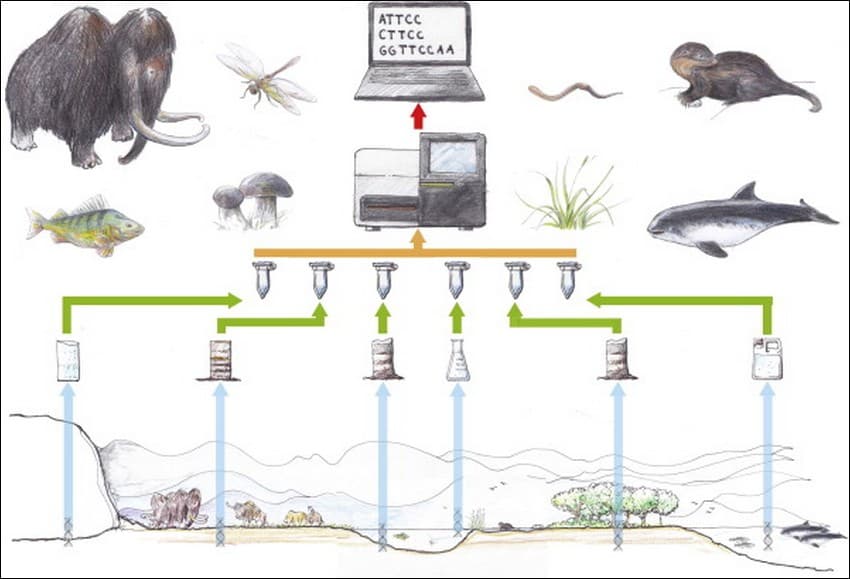

So how does it work? Any given sample of soil, air and water will invariably hold within it genetic material in the form of DNA of several organisms, numbering in their hundreds, together comprising the Environmental DNA. These genetic signatures within just a handful of sample can ravish us with a great amount of information on the species living there in that particular ecosystem, and not just of the species presently inhabiting the place, but also has the potential to shed light on the extinct species and the ancient environments in which they lived. The process essentially involves gathering samples of soil or water. These eDNA-carrying samples collected from the field are taken to a laboratory where the DNA is extracted from these samples using genetic methods. After that the extracted DNA is put through the process called DNA amplification using a scientific laboratory technique called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Simply put, several million copies of the DNA sequences are made through replication which allows the scientists to study the DNA molecules more closely. The DNA is then sequenced, which means the order of the building blocks of the DNA called nucleotides specific to each species is determined, that allows researchers to identify the species by matching the DNA sequences or “barcodes” with DNA sequences present in reference databases. This method of species identification is called DNA barcoding. eDNA can be used to detect and identify individual species, even the rare, inaccessible and elusive ones and can also be used to assess the biodiversity in a given region at large.

The newfound appreciation for the immense potential of eDNA has begun to see an explosion in its varied applications worldwide.

In Liberia, environmental DNA is empowering conservationists and communities to protect and preserve their precious freshwater ecosystems by helping gather the much-needed information on under-studied and data deficient species which is in turn helping to prioritise species that are at risk of extinction. So far nearly 170 species including critically endangered ones have been identified using eDNA.

World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is applying the non-invasive technique for a range of conservation projects including identifying individual polar bears using eDNA left behind in the tracks made in snow to study their subpopulations, or even assessing tiger prey populations in Bhutan.

Researchers in India, too, are testing eDNA based tools to detect a freshwater invasive fish species called suckermouth sailfin catfish (Pterygoplichthys spp.) and check its spread across India. Native to South America, the suckermouth sailfin catfish, a popular ornamental aquarium pet in India, is ravaging the ecosystems in freshwater bodies across the country. This hardy fish, with very few predators and capacity to thrive even in low oxygen conditions is displacing native species and has even established self-sustaining breeding populations in multiple locations. Researchers have turned to eDNA as a feasible, cost-effective, non-invasive, simpler option to detect the fish’s presence, and learn about its abundance and density.

The overall workflow for environmental DNA (eDNA) studies with examples of organisms that have been identified from environmental samples. Environments and their respective samplings from left to right: (i) glaciers; (ii) permafrost/tundra; (iii) aquatic sediments; (iv) lakes and streams; (v) terrestrial habitats; (vi) oceans. The first three are ancient environments while the latter three are modern. Credit: Drawing by Lars Holm; Source: Philip Francis Thomsen, Eske Willerslev, Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity, Biological Conservation, Volume 183, 2015, Pages 4-18, ISSN 0006-3207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320714004443)

The specific characteristics of eDNA, especially with regards to its shelf-life and decay behaviour prove particularly useful as it gives us a highly specific snapshot of the environment at a particular point in time. For example, eDNA found in an aquatic environment are relatively short-lived (a matter of few hours) as compared to those found in ice or soil. So, the DNA in a water sample will most likely be recently deposited by organisms.

Generally, eDNA follows a pattern of exponential decay over time. The fish above leaves its eDNA behind as it moves through the aquatic environment. The eDNA stays behind in the environment, and slowly dissipates over time. Credit: Yeswikipediaimarobot / Wikimedia Commons

Challenges facing eDNA

But, like most newly developing scientific methods and technology, environmental DNA’s methods too are undergoing phases of trial and error, refining, and waiting for existing resources and knowledge to catch-up, before they are completely understood and standard protocols are set up.

The meteoric rise of eDNA use in research and conservation in the recent times has also brought with it several limitations and challenges to the forefront. One of the biggest challenges in the way of completely capitalising on the usefulness of eDNA is the lack of comprehensive reference databases of DNA to identify species. Though strides in filling this knowledge gap are being made promisingly fast. DNA databases such as National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) that make DNA sequences publicly available, and the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) which is an “online collaborative hub for the scientific community and a public resource for citizens at large”, etc., are quite exhaustive. But there is still some way to go.

Apart from that, other limitations that underscore the use of eDNA include contamination of samples and errors in DNA sequencing, and the serious lack of state-of-the-art laboratories in many tropical countries.

“If we want [eDNA] to become mainstream and used on a large scale, we need to build capacity around the world, so that people can collect samples in the right way, analyze the samples in their countries, and use the results for their own conservation and monitoring purposes,” scientist Arnaud Lyet tells Mongabay.

A handful of soil or water is truly a microcosm of a much larger ecosystem. A grand little universe of eDNA carrying vast genetic information waiting to be decoded. Waiting to be fathomed.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

- From Under Our Feet

- Effects of Road Network on Gaur

- Averting Extinction – One Blood Sample at a Time

- Connectivity Conservation

- Why Pitting Ecology vs Economy is Dangerously Naive

- They’re Asked To Look After India’s Forests and Wildlife. Who Looks After Them?