Where a vehicle doesn’t reach, Girish Punjabi walks with the forest staff installing camera traps and recording signs and tracks of tigers, leopards, dhole, and sloth bears. He and his team covered nearly 850 km. on foot in 2019-20 alone, meticulously surveying a very important stretch of forest in the northern Western Ghats, a landscape he has been working in for the past 10 years.

Girish Punjabi installs camera traps along with the forest staff in Tillari Conservation Reserve. Credit: Rizwan Mithawala/WCT

Punjabi, Conservation Biologist with the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), has been gathering and analysing data to understand how the four large carnivores – tiger, leopard, dhole (Asiatic wild dog), and sloth bear – are faring along a critical wildlife corridor in the northern Western Ghats called the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor. Critical because for Sahyadri Tiger Reserve (STR) in Maharashtra the only remaining link to the nearest tiger source population is through this corridor that connects STR to a cluster of Protected Areas in Karnataka and Goa, namely Kali Tiger Reserve and the adjoining Bhimgad and Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuaries. In other words, the only way for tigers from Kali Tiger Reserve and the surrounding forests to disperse and colonise STR is by making their way up through this narrow corridor. There have been no known records of tigresses from STR in the recent past. So for tigers to be able to naturally colonise this tiger reserve and surrounding forests, the corridor needs to be protected and reinforced. Without the stretch of the forests that make up the Sahyadri-Konkan corridor, which is narrower than one kilometre in places, movement of long-ranging species and connectivity will be irreversibly hampered. The corridor is already under a lot of pressure from human activities leading to severe fragmentation. Hunting, intensive farming, expanding human settlements and linear infrastructure, and industries have led to the decimation of the corridor and large mammal populations in the region.

In 2019-20, as part of WCT’s long-term study in the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor, Punjabi and his team surveyed over 8,000 sq. km. by dividing the area into 44 grid cells (188 sq. km. in size each), walking 4 to 40 km. in every cell of this grid, detecting large carnivore signs, and analysing mountains of data to obtain an accurate understanding of what was really going on with the four large carnivores in the landscape.

Essentially, they strived to understand a) how the large carnivores are persisting within this corridor; b) whether the corridor continues to provide the necessary habitat for the carnivore populations; and finally c) how ecological and anthropogenic factors have influenced the use of the corridor area by the four large carnivores.

“The goal was to gain a thorough scientific understanding of the distribution of large carnivores in the landscape, by understanding the ecological, administrative, and anthropogenic factors influencing the species’ occupancy here,” explains Punjabi.

Photographs of tigers captured on camera traps in the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

So how are the four large carnivores faring in the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor? What did WCT’s study reveal?

In short, the study found that no viable population of tigers exists within the study sites owing to high levels of human disturbances. Only strict protection and restoration of the forests in the corridor linking good tiger habitats in Maharashtra and Karnataka can help to achieve a gradual improvement in the tiger population. Human disturbance and loss of prey were negatively impacting dhole populations. Leopards, owing to their brilliant adaptability, were persisting in PAs as well as human-dominated spaces where they prey on small-sized livestock and domestic dogs/cats. But the presence of wild prey and Protected Areas was important, and in all probability helping to keep human-leopard conflict from escalating further.

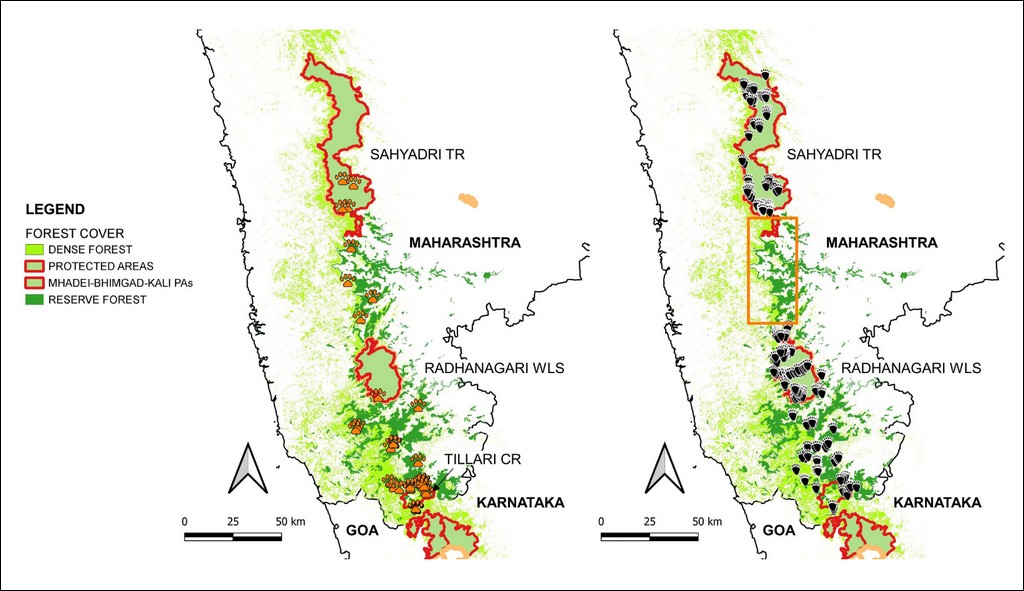

Of the big four, sloth bear, the study finds, has suffered the worst impacts of historical fragmentation and hunting. “WCT’s findings indicate that sloth bears in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve are virtually isolated from the population further south in the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary and beyond (See the map below). The lack of gene flow between Protected Areas can be a serious problem for the long-term survival of the species in the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve, and can reduce genetic variation. It is likely that the existing narrow corridor is insufficient for sloth bear dispersal and concrete steps will be necessary in the future for sloth bear conservation,” explains Punjabi.

Upon looking closely at these two comparative maps of detection signs of tiger (left) and sloth bear (right) along the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor, one can notice that there are no bear signs between Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary. This shows that the sloth bear population in Sahyadri is isolated from the population down south, indicating the species’ sensitivity to habitat fragmentation and hunting. Credit: WCT

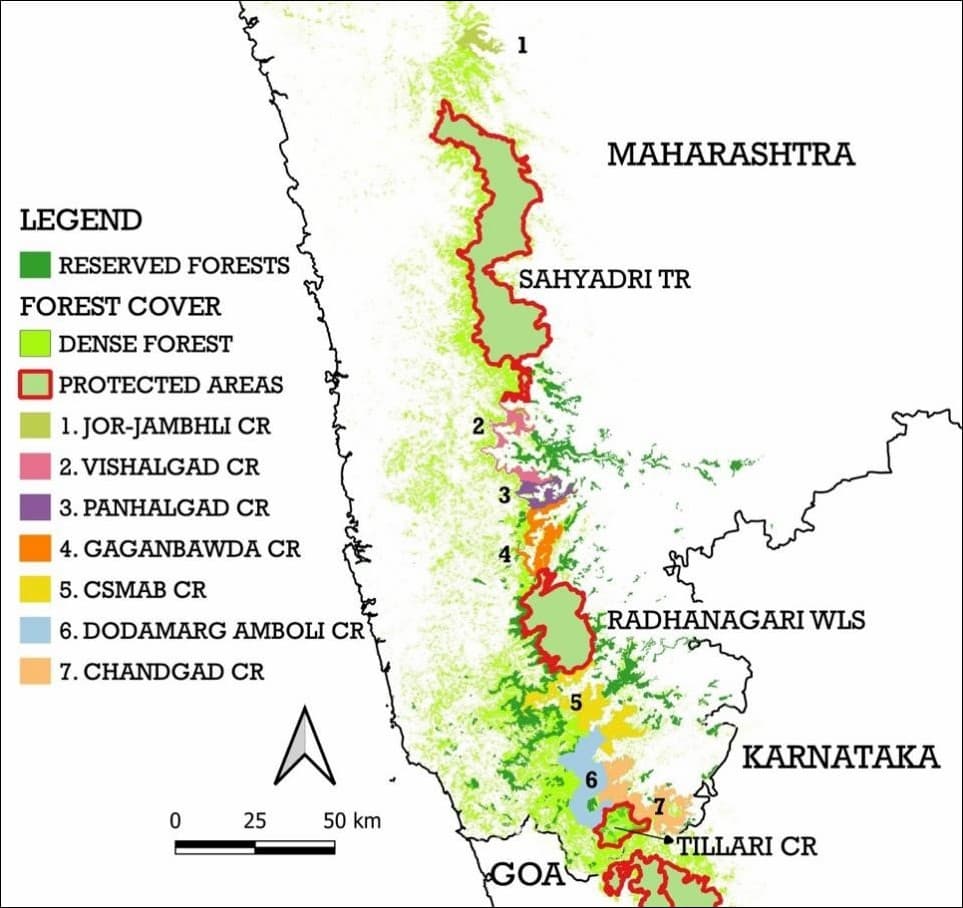

WCT’s study helped highlight the need for stronger protection of the large carnivore populations and declaring more tracts of forests as Protected Areas in order to secure the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor. Finally, in a series of landmark decisions by the Maharashtra Government, between 2020 and 2021, a number of new Conservation Reserves (CRs) were approved in the Sahyadri corridor, effectively offering formal protection to nearly 900 sq. km. of this vital habitat. There are very few other wildlife corridors in the country which are formally protected this way in their near-entirety.

The recently notified Conservation Reserves (CRs) along with the already existing Protected Areas have brought the near-complete linear stretch of the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor under varying degree of legal protection. (CRs 4 & 5, Gaganbawda and CSMAB in the map are as yet not notified) Credit: WCT

Consolidating Protection of the Corridor

“In June 2020, the State Government of Maharashtra notified an area of 29.53 sq. km as the Tillari Conservation Reserve. This region is a vital pinch-point in the corridor for movement of tigers and other large mammals between three states – Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka. Efforts to declare Tillari as a Protected Areas started in 2014 and was realised after six years when it was notified as a CR. Following in the footsteps of Tillari, multiple new CRs have been notified, protecting an additional 874 sq. km. of vital tiger habitat in the Sahyadri corridor,” explains Punjabi.

Since the declaration of the Conservation Reserves, WCT has been working in close collaboration with Maharashtra Forest Department to develop an effective Management Plan for better protection. “It essentially lays a blueprint for conservation measures to improve wildlife habitat and populations, at the same time, prescribes how local people can benefit from these Protected Areas through sustainable agriculture, ecotourism, and social welfare schemes.” WCT has also conducted extensive training for over 300 frontline forest staff under this project over the last two years, with nearly 30 training workshops organised collectively on wildlife law enforcement, crime scene investigation, trauma management, and wildlife monitoring.

WCT, in collaboration with the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and Territorial Circles is also systematically camera-trapping in seven CRs to assess the minimum population of large carnivores there. This is the first time ever that the CRs in the corridor area of the Sahyadri landscape are being thoroughly camera trapped.

“During our previous extensive study of the corridor in 2019-20, the team systematically surveyed this landscape on foot and opportunistically placed camera traps in a few areas, but a thorough camera-trap survey was necessary to get a complete picture,” says Punjabi.

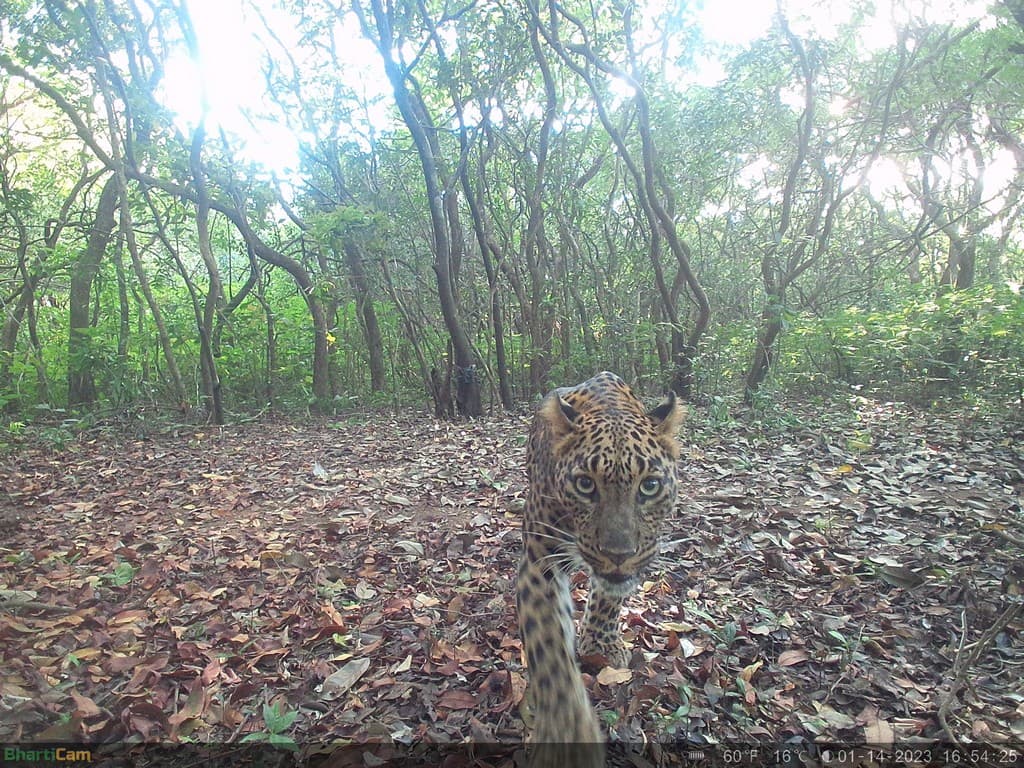

An Indian leopard captured on camera trap in a CR this year. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

“To get a good measure of the population size of at least two large carnivores – tiger and leopard – we are assessing the minimum population size and their density to inform future management actions within the CRs. We also wanted to understand which are the areas where large carnivores breed. This is important so as to direct improved management attention to certain areas, such as improved patrolling, camera trap monitoring, and avoiding forest diversion,” he further adds.

Punjabi and his team have since obtained interesting results from the camera trap surveys in the CRs. Overall, the camera traps have so far revealed 27 species of wild mammals including small-clawed otter and gaur. “We got a Malabar giant squirrel for the first time on camera-trap! Though they’re fairly easy to spot in many parts, they rarely descend to the ground,” says Punjabi excitedly.

Here are some interesting natural history moments captured on WCT’s camera traps –

A cool sequence of videos of a sloth bear with cubs on her back approaching a tigress (whose shining eyes are clearly visible!) and quickly turning around (top), and the tigress emerging a few minutes later.

A Brown palm civet, plausibly a leucistic individual. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

A gaur calf bolting (top) and moments later an adult leopard appears at the scene (precisely 7 seconds apart) (bottom). Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department.

A picturesque image of gaur with the Sahyadri mountain range in the background. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

A brown fish owl preys on a bullfrog. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

The camera traps were installed systematically in large grids, each cell four square kilometres in size, totalling up to 102 camera trap locations. This required Punjabi and his team to walk nearly 328 km. for deployment of cameras since many forest areas are inaccessible by vehicles. Many key findings have emerged from this camera trap survey of the recently notified CRs.

While gaur was the most photographed species indicating how widespread this large herbivore is in the landscape, the least photographed species included the four-horned antelope and golden jackal, both of which are uncommon in the landscape.

WCT has uncovered the presence of eight adult tigers, two tiger cubs, and 46 leopards in the CRs through this camera-trap survey. The survey resulted in the first-ever calculation of scientifically robust density estimates of the leopard and tiger in the Conservation Reserves of the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor. All this information is vital to assess how changes in forest management practices affect these large carnivores over the years.

Other interesting small carnivores and threatened species that were recorded in the CRs include the Asian small-clawed otter, rusty-spotted cat, leopard cat, stripe-necked mongoose, the endemic brown palm civet, and Indian pangolin.

Leopard cat. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

Asian small-clawed otter. Credit: WCT/Maharashtra Forest Department

“The aim of our work is simple. We want to improve management of CR areas in the corridor such that it retains its functionality over the long-term. This is vital in the case of the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve as there is only a single linear corridor connecting this reserve to Kali Tiger Reserve in Karnataka. Any further break in connectivity will severely affect its functionality,” concludes Punjabi.

Note: WCT’s conservation research project in the Northern Western Ghats focused on the protection of the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor is being undertaken in collaboration with the Maharashtra Forest Department with support from Vinati Organics Ltd.

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

Related Links

- Securing the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor

- International Tiger Day 2021

- The Curious Case of India’s Wildlife Corridors

- Camera Trapping Outside Protected Areas

- The Art of Camera Trapping for Conservation