“Every contact leaves a trace” says the ‘Locard’s Exchange Principle’, a simple and powerful premise on which forensic science rests. Any scene of crime, even wildlife crime, is replete with different forms of evidence waiting for a trained, forensic eye to scientifically interpret them, be it animal DNA, poacher’s fingerprints, or digital trails of illegal wildlife trade deals struck online. Forensic analysis helps further the investigation and build a water-tight case that can withstand scrutiny in the court of law and bring the perpetrators to justice.

An Indian pangolin photographed in central India. Pangolins are among the most imperiled species in the world. They are heavily poached for their scales and meat for the brutal wildlife trade. Photo: Aditya Joshi

Unfortunately, wildlife investigations often fall short due to weak understanding of evidence, poor handling of evidence, lack of infrastructure, training, support and funding. To tackle something as big and savage as the wildlife crime nexus, law enforcers need all the help they can get in gathering and analysing evidence that bolsters investigations in favour of the hapless victims – the wildlife – illegally captured, bred, tortured or killed for misplaced beliefs or frivolous global demands of the rich, the powerful, and the ignorant.

Today, illegal wildlife trade is the fourth largest and most profitable organised crime industry in the world, with only drugs, humans and arms trafficking ranked higher on this deadly list. Wildlife crime has ballooned into a multi-billion-dollar industry whose wily tentacles have penetrated and decimated not only wildlife, causing species extinctions on a mass scale, but also has devastated economies, lives, and livelihoods. In 2016, the annual value of illegal wildlife trade was estimated at up to $23 billion by the United Nations. A large amount of this blood-stained money is estimated to be funnelled into funding the terrorism activities of global terror groups and militias.

In India, low conviction rates and poor quantum of judicial punishment meted out to even the deadliest wildlife offenders makes committing a wildlife crime a low-risk-for-high-reward transaction. Law enforcement agencies are caught in a perpetual arms race of sorts with the ever-evolving modus operandi of wildlife crime. But enforcement agencies must adapt or remain a step or two behind the enemy.

Forensic science is fast arming the world of wildlife law enforcement with stronger investigative powers, deeming more and more evidence irrefutable in the court of law. Wildlife Forensics Head at the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), C. Samyukta, tells Conservation and Science Writer Purva Variyar, about how forensic tools can give us a fighting chance against wildlife crime; why India’s conviction rate in wildlife cases is so dismal; how she is using her forensics expertise to train and equip the country’s forest staff with improved knowledge of wildlife laws, crime investigation and forensic analysis through specialised programmes; and she also goes on to demystify the ‘CSI effect’.

Samyukta (Sam), at the onset, could you in simple words tell us what forensic science at its core really is? Because there are various romanticised interpretations of this field in the minds of non-experts like me, thanks to the ‘CSI effect’!

Forensic Science is, at its very core, an amalgamation of sciences used for solving a crime. In all kinds of crime, it is used to establish the links between the criminal, the crime scene, and the crime. Forensic scientists are trained to take a piece of evidence from the crime scene and put it through a battery of tests to derive information that will help advance an investigation. In other words, forensic science acts as a fact-finding tool for crime scene investigators.

Like with any other science, reliable results require time and patience. However, thanks to the glamorised version of forensics that TV shows have presented over the years (commonly referred to as the CSI effect), people have come to think of forensics as some magic wand that will give investigators all the answers they need to nab a criminal and that too in the time frame of a single episode! This could not be further from the truth. Forensic science has in equal parts both powers and limitations in terms of what kind of information it can glean from evidence, and the process can take weeks or even months.

Why is the business of wildlife crime so highly lucrative? What is driving this burgeoning trade?

There are systemic issues behind this. Policy makers don’t treat wildlife crime with the importance it deserves and consequently, don’t design strict policy or allocate sufficient budgets for combatting it. Enforcement agencies are often not trained and/or setup specifically for wildlife crime investigations, making it a secondary or tertiary priority for them. Wildlife crime cases that do end up in the courts are often so weakly constructed that judges, who are already dealing with heavy caseloads, have little way out other than to dismiss these matters prematurely or to deliver weak sentences. This leads people to callously believe that wildlife crime is not as serious as it is made out to be. Collectively, these actions create a vicious cycle that allows criminals to perpetrate heinous acts against wildlife, knowing fully well that if they do get caught, the worst they will receive is a rap on the knuckles. As a result, not only is wildlife crime booming, but with each passing day the number of species being victimised is increasing.

Tiger parts such as paws and teeth being illegally sold at a black market in Myanmar. Body parts of tigers and such other endangered and rare wildlife are in huge demand, especially in certain Asian countries, largely for unscientific use in traditional Chinese medicine. Photo: Dan Bennett/Public Domain

Speaking specifically of illegal wildlife trade, it has grown to be a ~20-billion-dollar industry thanks to several factors which cut across borders, both domestic and international. For instance, the demand for wildlife is one of the key drivers and comes in myriad forms. It could be from a pet enthusiast who wants to add an exotic or local species to his collection. It could be from a businessman who wants to increase his wealth by adding a star tortoise to his feng shui protection measures. It could be from a religious person who wants to ensure that his deities have nothing but the best peacock feather fans and ornaments. It could be from an industry that wants to produce medicine or construction material using unregulated wildlife by-products. It could be from a community that feeds on wildlife as the primary source of protein or due to dietary habits – a scenario that is now believed to be the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic. It could just even be from a person who wants to own a piece of the wild for cultural reasons or simply to look ‘fashionable’. Thus, when the demand is high and conviction rate low, the illegal trade of wildlife explodes.

Sam, do tell us about the power of immaculate evidence in the court of law and how forensics helps to consolidate it.

Just like a doctor will prescribe medicine based on the nature and severity of symptoms presented by a patient, the Criminal Justice System is designed to prescribe sentences on the basis of the quality of evidences presented and the strength of facts established by investigating officers. A judge cannot depend upon hearsay and is bound by law to use irrefutable and reliable evidence presented in the court to come to judicial conclusions. Thus, evidence is paramount to the delivery of justice.

As a thumb rule, in India, a suspect is deemed to be innocent until proven guilty; and with rare exceptions, the investigating officers have to establish the suspect’s guilt. No matter how compelling the testimony of the investigating officers may be, unless it is corroborated by sound evidence, the judge cannot take it into consideration. Here is where forensic science comes into play. The reports provided by forensic scientists help to not just prove evidence to be reliable and show them to corroborate the facts of a case, they also establish facts beyond reasonable doubt – another tenet by which a judge is bound. However, if the evidence itself is questioned and thought to be compromised (a tactic employed frequently by defence lawyers), then the value of the evidence could be nullified or lost.

C. Samyukta interacts with the forest staff in Manas Tiger Reserve as part of the Wildlife Crime Investigation and Wildlife Forensics training programme collaboratively organised by WCT and Aaranyak in January 2021. Photo: Jimmy Borah/Aaranyak.

Conviction rate in wildlife cases is dismally low in India. Less than 5%. Where is the law enforcement and judiciary falling short?

As I said earlier, both law enforcement and the judiciary are suffering at the hands of an ailing system. While it is everyone’s best intention to ensure that wildlife criminals are put behind bars, the hands of these key players are tied in one way or another. The commitment and efforts of an enforcement officer to investigate wildlife cases determines the quantum of punishment a judge will award the criminal. Thus, enforcement officers need to become more aggressive in their work against wildlife crime and ensure strict implementation of wildlife law. Judges need to be sensitised on a war footing and given the tools they need to issue strict punishment for wildlife criminals. While there is still apathy among a few players from both sides, they can collectively make a significant impact on conviction rates when they look at wildlife crime with the gravity it truly deserves. When this begins to happen, policy makers will have little choice but to create far better policy measures and allocate sufficient budgets to tackle wildlife crime. Surely, conviction rate is then bound to drastically increase and the law will start acting as a deterrent for traders and poachers.

To what extent is forensic science applied to wildlife crimes in India? Which and how many forensic laboratories are equipped to assist in wildlife investigation in India at the moment? Is development of more such specialised facilities and infrastructure in the pipeline?

There are a handful of laboratories in India that focus solely on wildlife forensics. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun, the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Hyderabad, Advanced Institute for Wildlife Conservation (AIWC), Chennai, as well as laboratories set up by the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) and the Botanical Survey of India (BSI) are among them.

Since the investigation of wildlife crime is pivoted on the accurate identification of the species targeted by the criminal, these labs are predominantly focused on DNA evidence or morphological evidence. Sometimes, such an identification may not be possible due to the paucity of ‘standards’ that enable forensic scientists to compare their results and conclude identification. Also, human evidences from wildlife crime scenes (such as poison, bullets, firearms, footprints, vehicles, traps, cyber evidence, etc.) are required to reconstruct the crime scene and link the criminal/s to the scene. However, forensic labs that work on human crimes are over-loaded with case work and often cannot deliver timely reports. Consequently, forensic science is underutilised in wildlife crime investigation in India.

Of late, government agencies have taken serious cognisance of the fact that effective wildlife crime investigation requires analysis of both wildlife and human evidences, and that the lack of either one can seriously damage the strength of a case. The Centre and some states have begun the process of building multi-disciplinary wildlife forensic labs; but their current pace of development is causing them to fall behind in the race with the growing crime rate.

Could you tell us about WCT’s crime investigation and forensics training programme for the forest staff across the country?

In cognisance of all the systemic problems that hamper wildlife crime investigation and the rate of conviction of wildlife criminals in India, WCT has been working from the ground up to improve the capacity of forest staff to investigate and combat wildlife crime. Since forest staff, particularly forest guards, are the first responders to a wildlife crime scene, the actions they take at the crime scene determines the future of the case. In the past, we have seen that the lack of appropriate training has led forest staff to repeat erroneous crime scene processes passed down to them by their predecessors. To counter this, we have developed training programmes that improve their understanding of evidence, give them skills for accurately handling evidence, and improve their capacity to utilise evidence and forensic reports to establish better cases for presentation in the court of law. We have also provided all our trainees with forensic kits that contain all the items they need to prevent tampering of crime scenes and to collect evidences in a scientifically-sound manner. Since the inception of these programmes, we have seen that guards are no longer intimidated by evidence.

Thus far, we have implemented these programmes in several tiger reserves across the Central Indian Landscape as well as in other key tiger habitats. In the offing, we have planned programmes to improve wildlife crime investigation by senior officers of the State Forest Departments and other agencies. We hope that with increased implementation of these programmes both within and outside Protected Areas, forest officers will be able to maximise the potential of evidence and build strong cases using improved investigative skills.

Forest staff investigating a mock crime scene as part of a wildlife crime investigation and forensics training programme conducted by WCT in Manas Tiger Reserve. Photo: C. Samyukta/WCT

Sam, you have always stressed upon the urgent need for heightened understanding of wildlife law and crime among lawyers and judges. Could you elaborate and also share how WCT is working to effect this?

Alongside policy makers and enforcement officers, lawyers and judges are key stakeholders in the efforts to combat wildlife crime at all levels. WCT has been actively working with both these players of the judicial system through several programmes. We have been conducting regular sensitisation workshops for judges, especially of sessions courts, in collaboration with State-level judicial academies. We have provided bursaries to ensure that good lawyers are available to Forest Departments. We have also created a moot court competition to increase awareness of wildlife conservation and its challenges among law students, and to draw law students to wildlife law practice. These efforts have started to show results, with more judges showing seriousness towards wildlife cases and more young law students showing interest in wildlife matters. We hope that in the coming years these efforts will also ensure that wildlife law is taught as a mainstream subject in Indian law schools, that sound legal talent will be routinely available to enforcement agencies, and ultimately, that landmark judgements will be delivered on wildlife matters.

There is more to forensics than DNA profiling and analysing fingerprints. Can you briefly touch upon the diversity of applications of this fascinating field?

Forensics is an umbrella science as several scientific disciplines are included and used under it. Sometimes even within a single case, several sciences and even non-sciences like art, accounting, and architecture can be used. Unfortunately, only DNA profiling and fingerprint analysis have come to be seen as forensics in people’s minds.

In crimes such as murder, theft, arson, etc., investigators rely largely on physical evidences from the crime scene, such as cigarette butts, clothing, firearms, poisons and even the dead body to piece together evidence about the suspect and the victim. In addition to forensic DNA analysis, this would require the use of disciplines like forensic botany, forensic odontology (dentistry), ballistics, forensic toxicology, and forensic medicine. With the increasing incidence of crimes, more recently developed forensic applications like cyber forensics, forensic accounting, etc. are now coming into play. There is tremendous scope for application of all kinds of forensics – both old school and new age, in wildlife crime investigation.

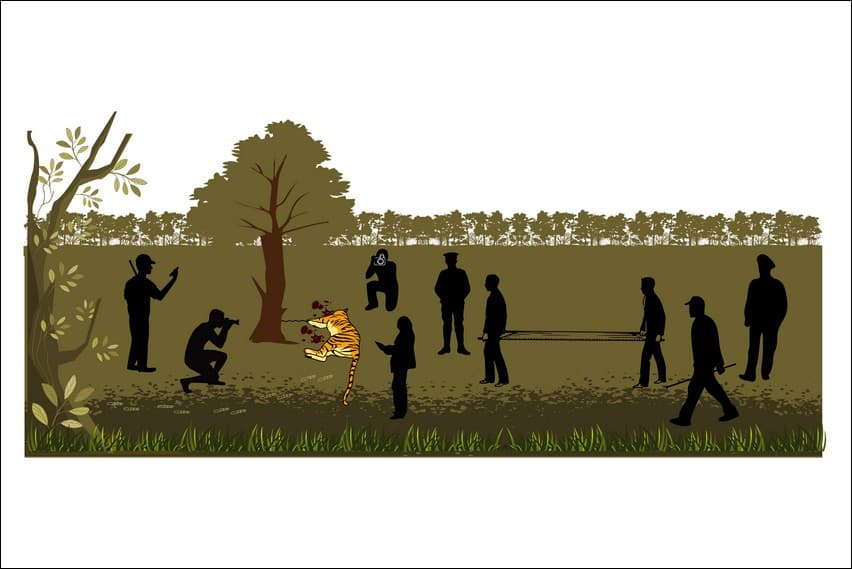

Take for instance a single case of a tiger hunt. From the crime scene, forest officers may recover evidences such as traps, bullet casings, discarded bottles, etc. They would send these to a forensic lab where scientists will use forensic DNA analysis to figure out which species of animal was hunted using the traps. They will use fingerprint analysis on the bottles to create a fingerprint profile of the suspects. They will use forensic ballistics to study the casings and figure out which weapon was fired at the crime scene. In the meantime, the officers will continue further investigation and may eventually catch the suspects. They may recover several evidences from them like tiger body parts, cell phones, weapons, identification documents, etc. Once again, the officers will send the items to a forensic lab where scientists will use DNA and morphology to confirm the authenticity of the tiger body parts. They will also use fingerprint analysis, DNA analysis, and forensic ballistics to link these suspects to the items recovered from the crime scene. They will use cyber and digital forensics to draw information from the electronic devices. They may even use forensic document analysis to authenticate the identity cards being carried by the suspects. With all of this information in hand, the officers can create a strong case against the hunters. Or, they could go a step further and use forensic accounting and cyber forensic tools to investigate the exchange of any information and money between them and suspected traders or buyers. In this way, forensic tools can be applied at all stages of the wildlife crime supply chain to identify several players in the nexus.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————