The amazing complexity of multicellular organisms arises from pure simplicity – a single cell. Organisms boast of their idiosyncratic morphologies which follow seemingly distinct paths but be it a human arm or a chicken leg, it all grows from a single cell, takes the same route.

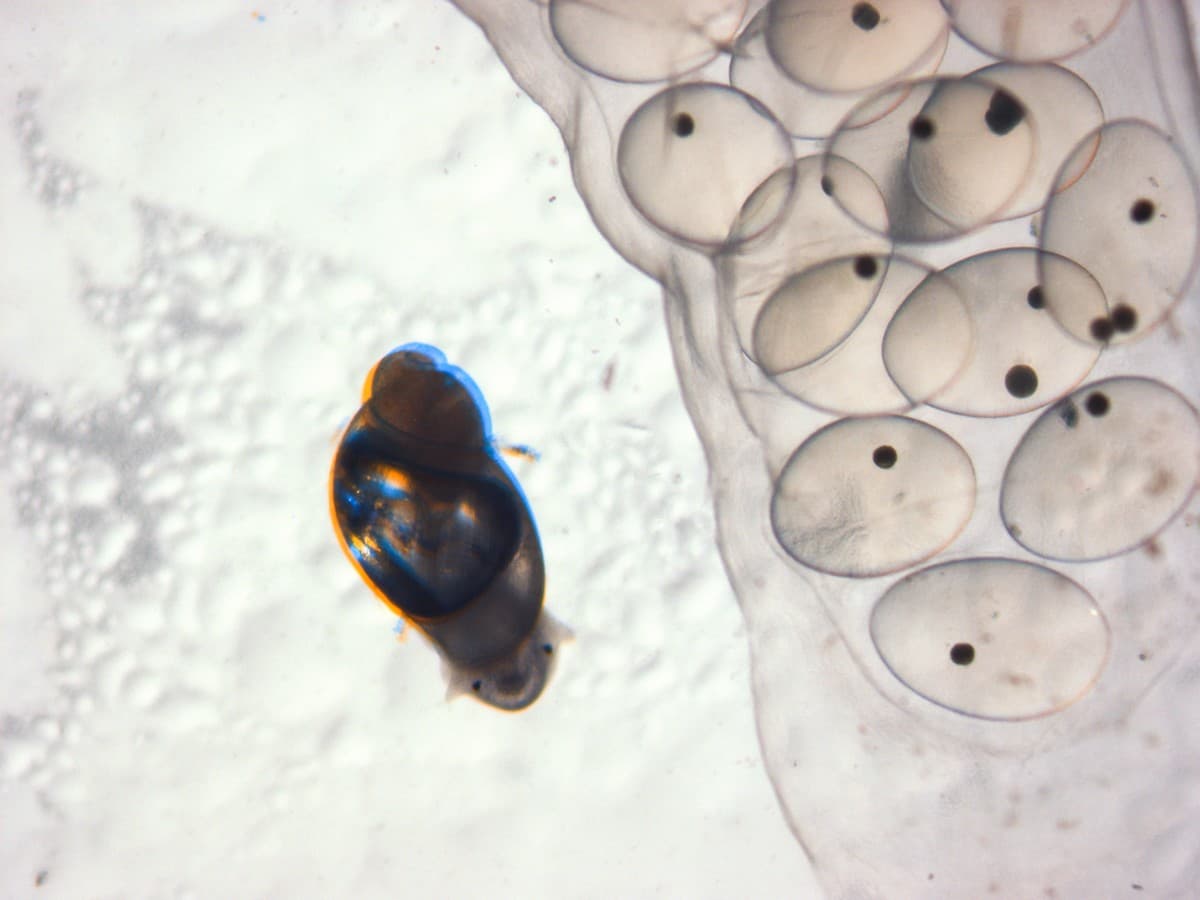

An adult pond snail (Lymnaea stagnalis). Photo credit: Purva Variyar

‘…Perhaps I ought to explain,’ added the badger, lowering his papers nervously and looking at Wart over the top of them, ‘that all embryos look very much the same. They are what you are before you are born – and, whether you are going to be a tadpole or a peacock or a cameleopard or a man, when you are an embryo you just look like a peculiarly repulsive and helpless human being…The embryos stood in front of God, with their feeble hands clasped politely over their stomachs and their heavy heads hanging down respectfully, and God addressed them. He said: “Now, you embryos, here you are, all looking exactly the same, and We are going to give you the choice of what you want to be. When you grow up you will get bigger anyway, but We are pleased to grant you another gift as well. You may alter any parts of yourselves into anything which you think will be useful to you in later life.’ T.H. White, The Once and Future King

Have you ever wondered how an organism comes to be, practically out of nothing, merely a single cell? I have always wondered about what happens from the time an egg is fertilised to the point where it turns into an autonomous organism. I have tried to capture the beauty in the development of an embryo of Lymnaea stagnalis, a freshwater snail, through the below series of photomicrographs. Presenting a photo story about this miraculous process of life. Read on.

Molluscs have been instrumental in developing our understanding of the fundamental processes of embryology and developmental biology, and Lymnaea stagnalis, among other freshwater snails, has contributed immensely.

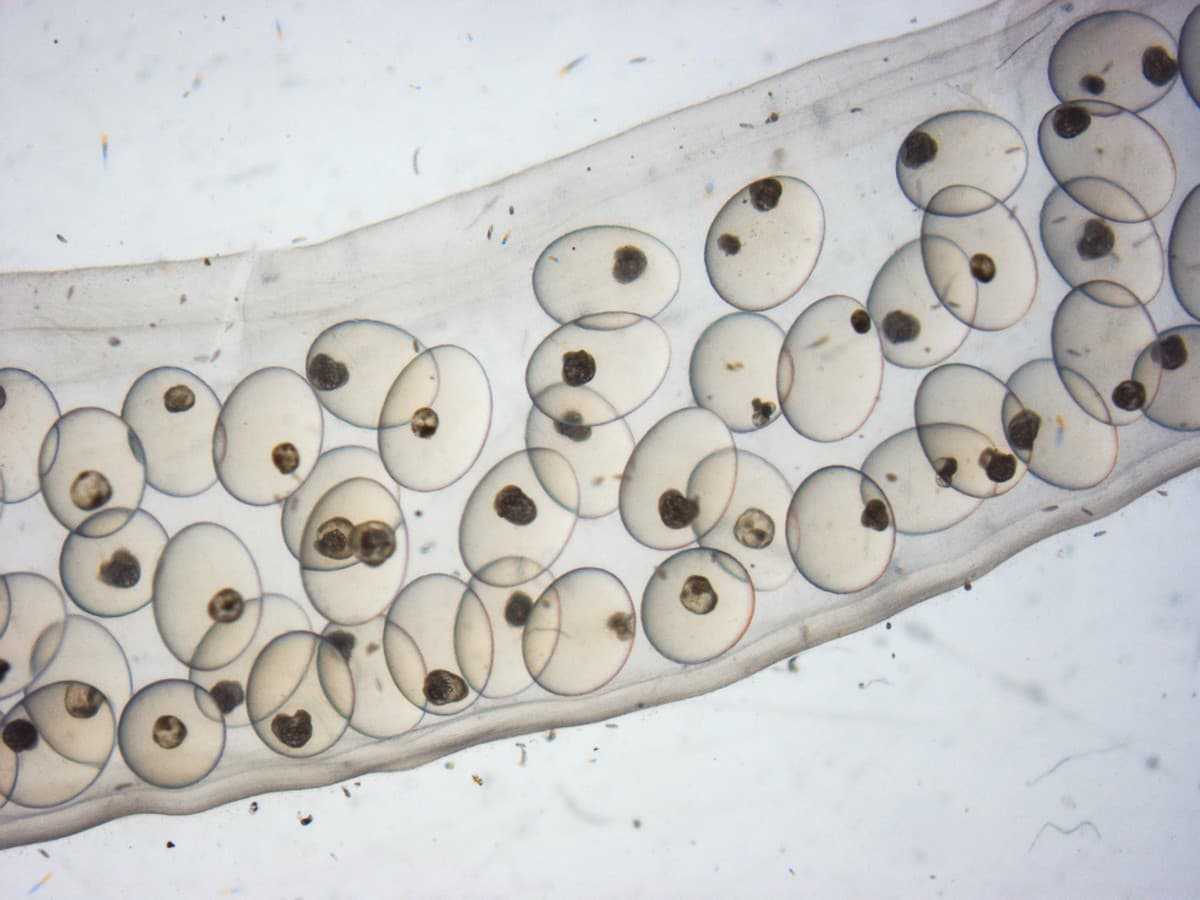

A female of the Lymnaea stagnalis snail lays eggs in large masses clumped together in a transparent egg sac that is about 1-4 cm. long. A sac carries a clutch of about 50-120 eggs. Each transparent, oval-shaped egg capsule measures about 1 mm. in diameter in which the embryonic journey of a single fertilized egg cell begins at about 100 µm (micrometersi) in diameter. (As seen under a stereo microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

This is a glorious sight of several freshwater pond snails in various embryonic stages. Every single one of those beautifully transparent egg capsules allows for the observation of a developing embryo, while also acting as a diffusion barrier that prevents the passage of large molecules. In other words, an egg capsule does a swell job of keeping the embryo within nourished and safe. (As seen under a stereo microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

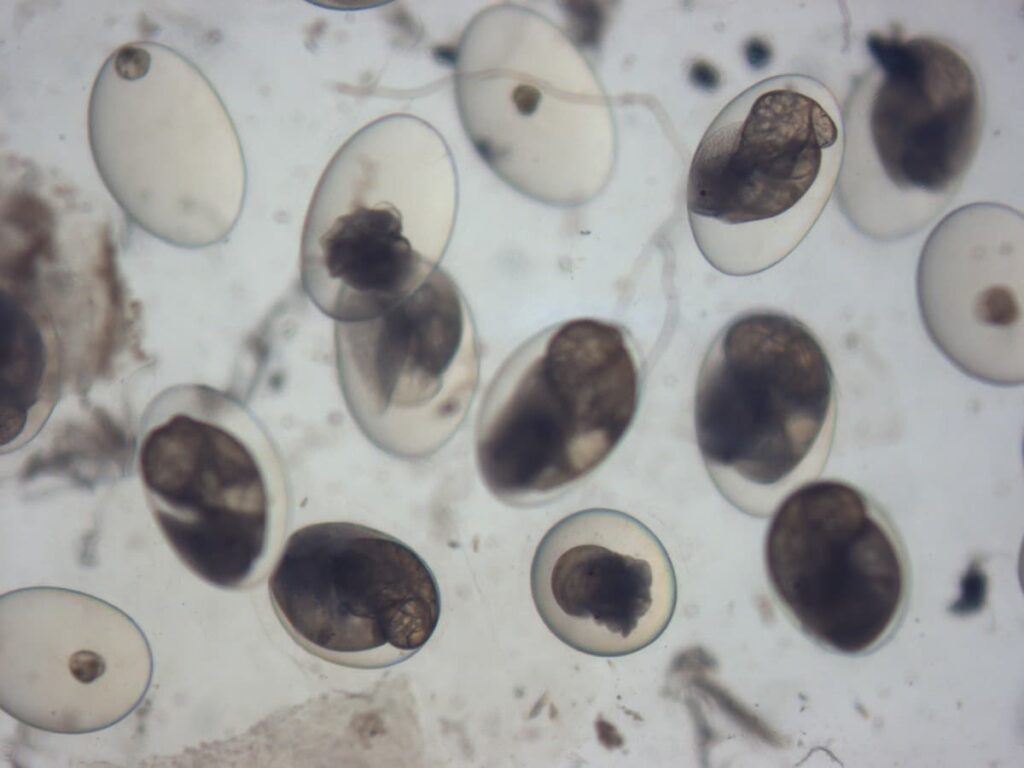

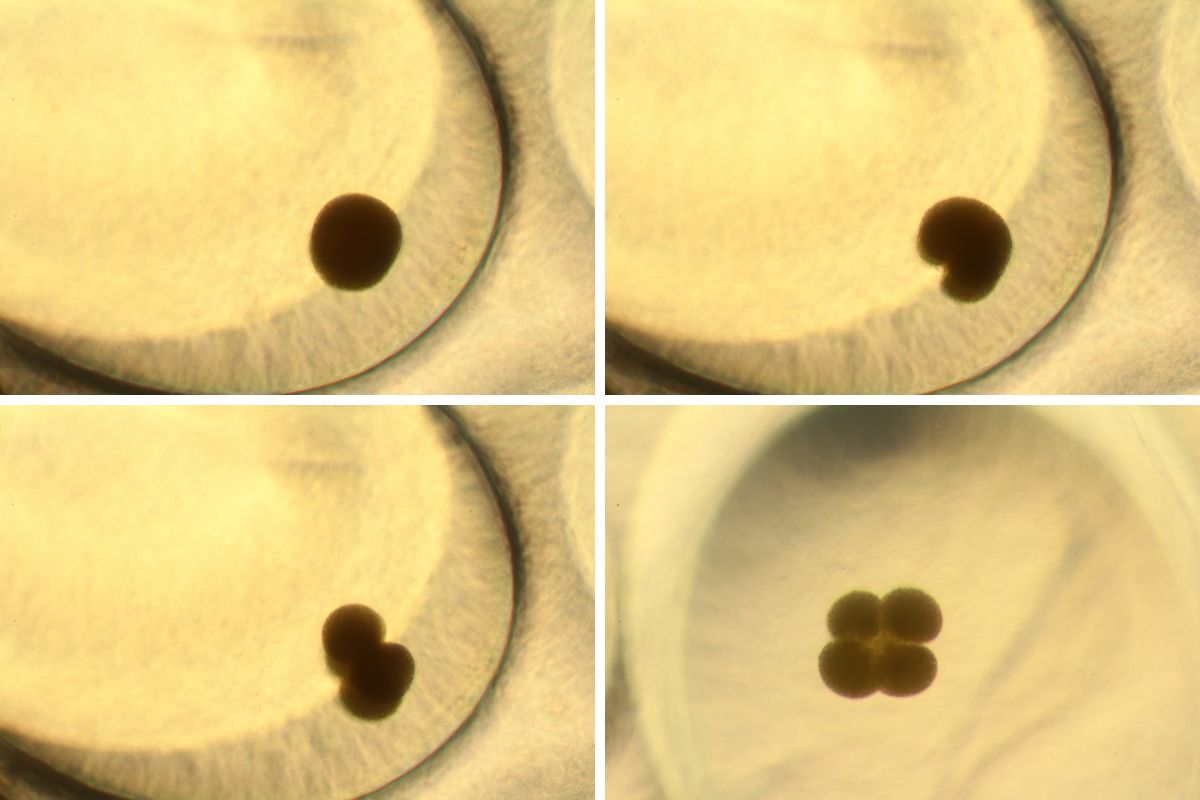

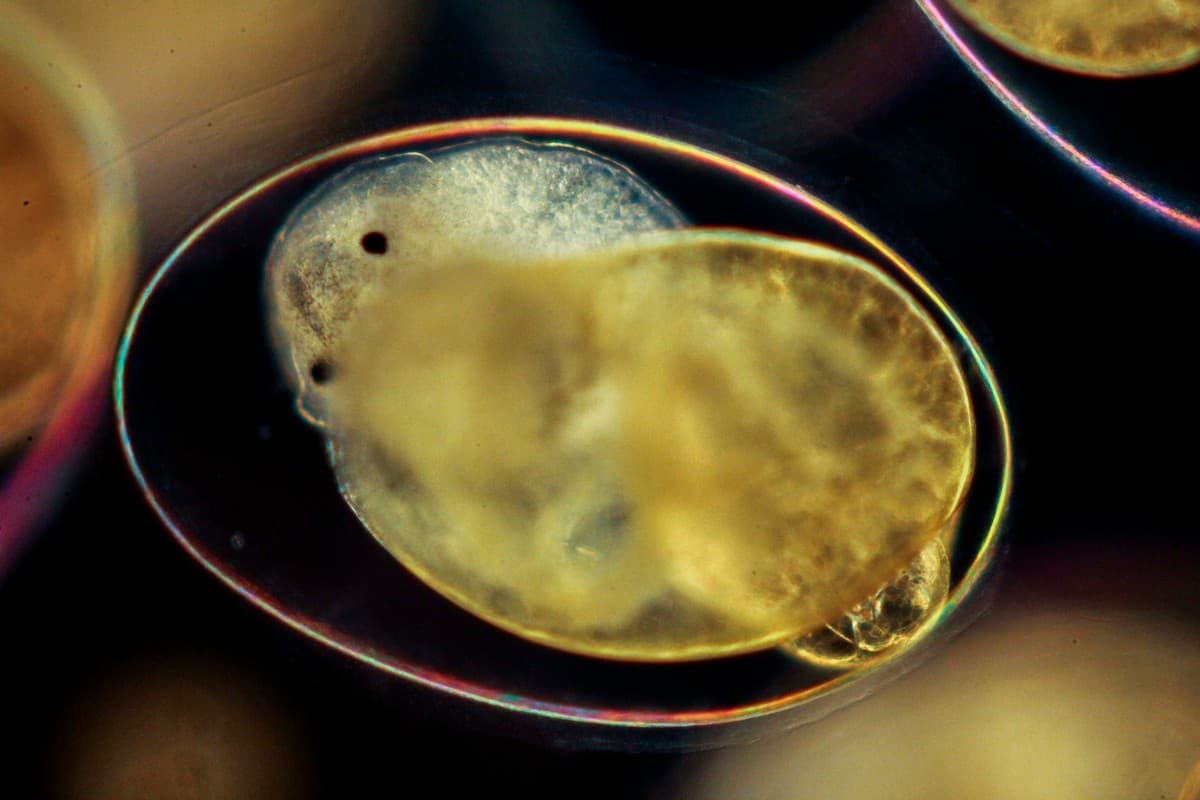

Lymnaea stagnalis lays eggs whose capsules are entirely transparent. This is why it is possible to observe the embryonic development of live specimens under a microscope. The journey starts off with a single-celled fertilised zygote, which almost immediately starts to divide. Several cleavages later, the embryo grows in size and cells in number, till it starts to discernibly acquire a distinct form. (As seen under a compound microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

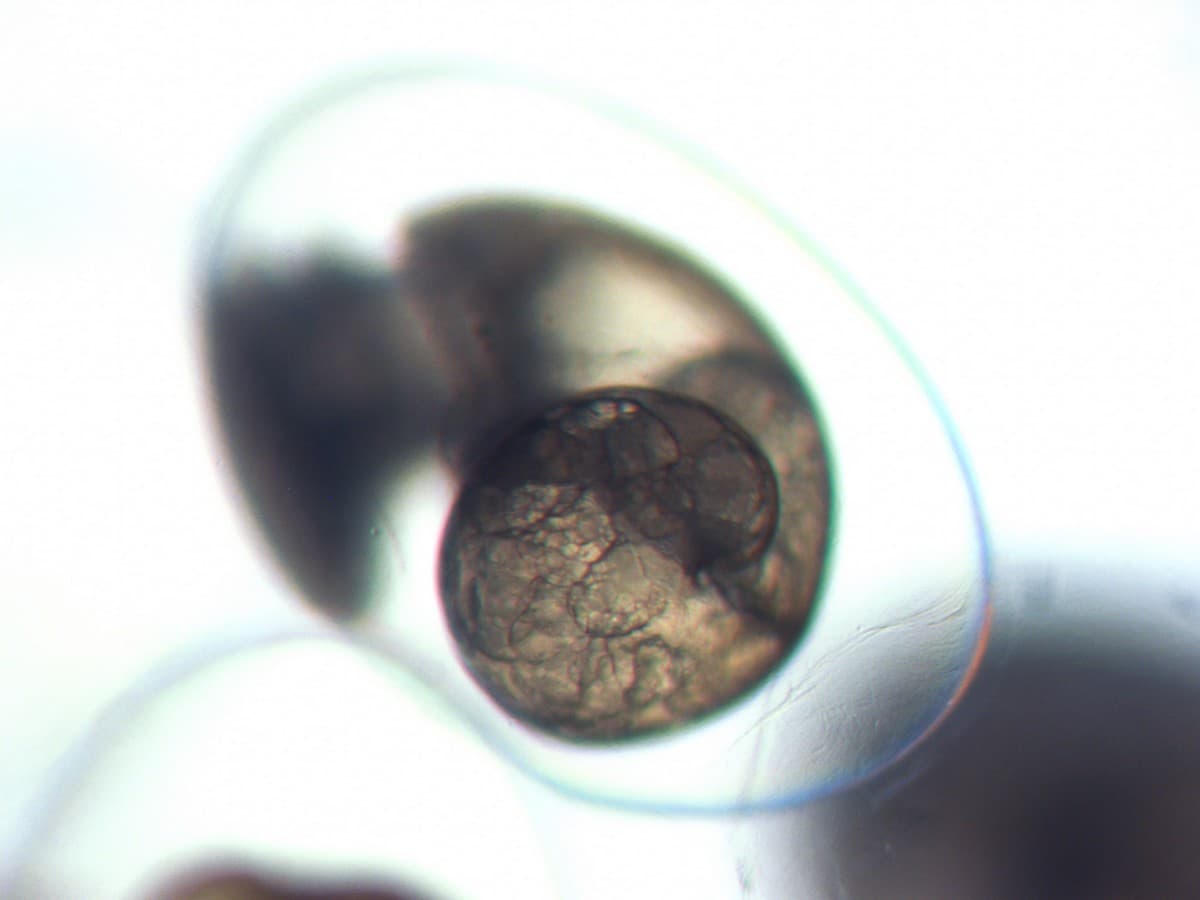

This is the trochophore stage of the snail embryo that develops within two days of the egg being laid. It’s when the cells are busy organising and gearing up for more specialised roles; the nutrient-rich fluid within the cell capsule ensuring this growth continues unabated. (As seen under a compound microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

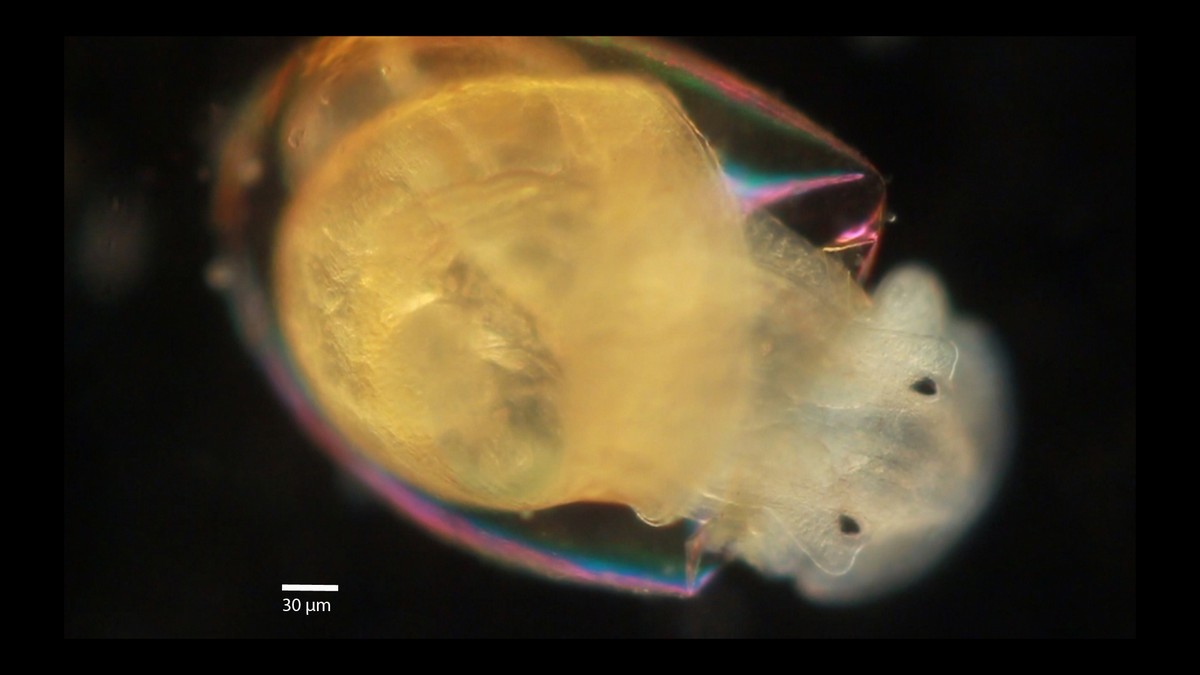

Soon, the embryo develops a bilobed foot, characteristic of a snail. A larval shell is formed and the first hint of asymmetry begins to show in the embryo. After about four days, the embryo enters the metamorphic period and begins to resemble a miniature hippopotamus when seen from the front. That’s why this stage in its larval life is termed the ‘hippo’ stage. (As seen under a compound microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Slowly, the embryo metamorphoses into a juvenile adult. The beautiful, distinct snail spiral is now clearly visible. This is marked by the appearance of rudimentary eyes and tentacles. The larval shell covers most of the posterior section and the lung and heart also slowly develop. (As seen under a stereo microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Once the primordial organs and tissues become more specialised and differentiate, and all the nutrients within the capsule get exhausted, the juvenile is ready to hatch and make its entry into the outer environment. Here, a juvenile is seen taking its first ‘steps’ into the world. A living being is born! (As seen under a compound microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Hardly 2-3 mm. long, the newly-emerged juvenile Lymnaea stagnalis possesses all the structures of the adult snail. This feat is achieved within a little more than a week’s time since the eggs were laid. (As seen under a stereo microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Remnant of an egg capsule just after a juvenile pond snail (Lymnaea stagnalis) emerged from it. Upon observing under dark-field, the diffracting and refracting light gave these brilliant blue and golden hues to the otherwise transparent, empty egg capsule. (As seen under a compound microscope.) Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Photo credit: Purva Variyar

Truly, I can’t think of anything more exciting than the process by which a single cell develops into an embryo and finally, into a complete organism.

i 1000 micrometres (µm) = 1 millimetre (mm)

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

Related Links

- Tide Pool Life

- Fossil Folklore

- Mouthing with the Insects

- Manipulative Frankensteins

- An Ode to the Giant Fungi of Yore

- 15-member panel to monitor wildlife plan implementation