Understanding the threats invasive species pose to native biodiversity

We, humans, are unarguably the biggest agents of change on the planet, today. Many of our actions, even smallest of them, tend to leave in their wake much unpredictable, magnified, chaotic consequences that have the potential to alter and modify ecosystems and their functioning.

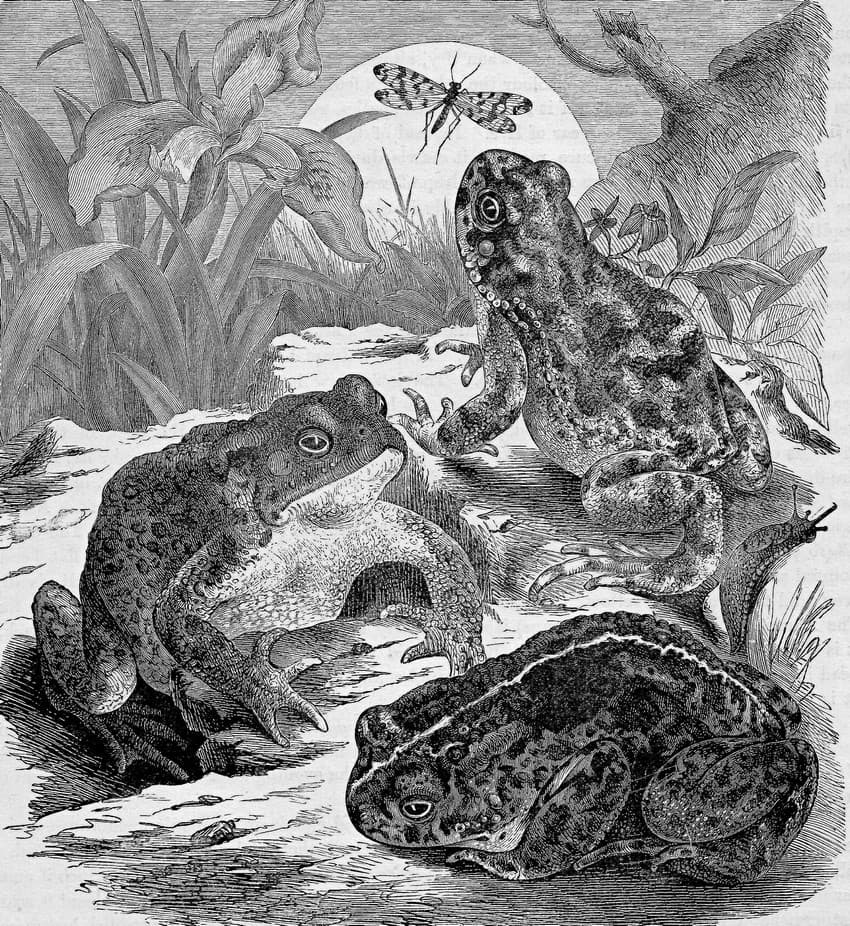

Invasive alien species of all forms – reptiles, mammals, amphibians, fish, fungi, plants, microbes, etc. – are ravaging ecosystems and economies all over the world. It is predominantly a man-made problem. Photo credit: MaxPixel.net

One such disastrous consequence of human actions is the problem of invasive alien species that is wreaking havoc in various pockets across the world – terrestrial and aquatic. Invasive species are one of the biggest causes of extinctions globally. The Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) regards ‘the biological invasion of alien species as the second worst threat to biodiversity after habitat destruction’. Innumerable species of plants, animals, fungi, and even microbes have found themselves introduced into newer and non-native environments by humans, thanks to globalisation. As the society became more and more mobile and people began to uninhibitedly journey between countries and continents with unlimited goods in ships and now airplanes, they inadvertently and knowingly, carried with them many forms of non-human passengers in the process. Some of these non-human forms came stuck to ships like the Zebra mussels, some rode with the people like the domestic cats and rodents, some were on their way to be traded as pets and ornamental commodities like the red-eared slider turtle and the American shrub lantana, while some others discreetly hitchhiked in the form of tiny seeds and spores such as the Parthenium, also called Congress grass.

What Makes Invasives Invasive?

Whatever be the mode of introduction, many of these unwitting creatures found themselves in fresh new, alien territories and environments where they were now the aliens. Introducing an organism artificially into any natural habitat is dangerous as it can potentially ‘shock’ an ecosystem by disturbing the equilibrium attained over thousands of years of evolution.

To be recognised as invasive, the introduced species must exhibit certain, unmistakable traits, which give them an edge and set them on the path to becoming harmful to the environment and/or the economy of the country or place it has been introduced into.

While not all non-native species turn invasive, those that do are quick to adapt to the new surroundings and environmental pressures, multiply quickly, are able to outcompete native counterparts for resources such as food and space, more often than not have no predators in newly introduced sites, but themselves may predate on or transmit diseases to native species who invariably cannot mount a defense against something they have never encountered before.

A very interesting example of a relatively recent incident of introduced-species-turned-invasive is that of the Asian toad (Duttaphyrunus melanostitcus), which is indigenous to India and other South and South-east Asian countries.

It is suspected that few individuals accidentally landed, a little before 2010, in the Toamasina port in eastern Madagascar along with shipments of mining equipment brought in from Thailand. This non-native amphibian quickly naturalised and colonised more than 100 sq. km. of land around ground zero. By 2018, the toad population had swelled up to several millions. These alien toads are causing merciless devastation of several native wildlife populations on the island country. The toad’s chemical defence mechanism is to blame. An unsuspecting predator upon trying to consume an Asian toad also ends up consuming deadly toxins called cardiac glycosides, which are released by the toad when threatened. The Asian toad possesses specialised parotid glands located a short distance behind its eyes which secrete a milky fluid carrying these toxins that can cause cardiac arrest in the animals with no immunity to the poison. In the Asian toad’s natural habitat, predators have either developed resistance to the toxins or have learnt to avoid them altogether. But, the predatory species of Madagascar have been blindsided by the introduction of the Asian toad which is poisoning the unique and rare fauna of the island. Eradication efforts are on.

A very famous example of man’s pet trade antics gone awry is that of the Burmese python (Python bivittatus) conquest of the Everglades National Park in South Florida, USA. Native to southeast Asia, the Burmese python wound up in North America when several individual snakes were brought in as pets, and were either released in the swamps of the Everglades or were escapees. These large, non-venomous constrictors have multiplied to the point of establishing a breeding population in the Everglades National Park and have decimated populations of native mammals, birds, and reptiles.

Brought to the USA as a pet, the Burmese python has infiltrated the swamps of the Everglades National Park, Florida, and are decimating the prey population there. Photo credit: Everglades National Park/ Flickr

Even more startling cases of invasive species and their impact on natural surroundings abound.

Invasives colonising islands can be particularly catastrophic to the native biodiversity. A good example is that of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis), native to Australia and Papua New Guinea, individuals of which were unintentionally introduced in Guam, a South Pacific island in 1940s (or 1950s). Soon, the snakes proliferated and preyed on indigenous wildlife, causing the extinction of as many as nine bird species on the island.

And it is not just amphibians and reptiles. Crustaceans such as the zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), native to Eurasia, made their journey to various locations across the world in the ballasts of ships. These have pushed out native freshwater filter feeders in several parts of North America and have also gravely affected the region’s fisheries, aquaculture and water transport.

“Invasive alien species are as anthropogenic as dams and highways and at times even more damaging to natural ecosystems. They eat out or outcompete native species and cause tremendous imbalances in nature. We need to be careful of everything we have, grow, and rear from ornamental plants to exotic pets,” says Gerard Martin, a renowned herpetologist and nature educator, and co-founder of The Liana Trust, a conservation and education NGO based in Karnataka, India.

India’s Biological Invasion

India has had its own gargantuan share of troubles with the invasives to contend with.

About 157 invasive animal species were listed by the Zoological Survey of India in 2017, and this inventory ranged from birds, reptiles, mammals, molluscs and fish across land and freshwater habitats, as well as marine invasive species of annelids, more arthropods, cnidarian, bryzoans, molluscs, ctenophora and entoprocta. Even insects (e.g.: Cotton mealybug, coffee berry borer beetle, etc.), plants, microbes, fungi, too, make it to this inauspicious list of invasives in India.

You may wonder about alien plant species and how they could possibly resort to causing serious harm to the native biodiversity and environment. They most definitely can and usually are deliberately introduced for ornamental or agricultural purposes or accidently spread as seeds and spores that get caught in the web of global transportation, riding on people’s clothes or goods. Just like with animals, not all introduced plant species become invasive. But, those that do, reveal special characteristic features. They are remarkable generalists and are usually abundant in their native range. These plant species show ‘phenotypic plasticity’, that is they are able to easily adapt to a wide range of physical and weather conditions and soils. Their ability to produce large number of pollen and seeds and easy dispersal mechanisms ensure their wide and rapid spread. They often have short life cycles, germinate fast, grow aggressively and abundantly stake claim to the space and resources.

India, studies show, is at a severe risk of having nearly half of its geographical area colonised by invasive plant species! So far, over 200 plant species have been identified as invasives in India, making it one of the worst hit countries with respect to plant invasives.

Common lantana (Lantana camara) is one of the worst invasive plant species to affect India’s forest ecosystems. Photo credit: Samratmaina2019/Wikimedia Commons

Take a close look at the image above. You are looking at a Lantana specimen, one of the worst invasive species in the world. Lantana camara or Common Lantana arrived in India in the 19th century as an ornamental plant. Soon, this extremely versatile and adaptable tropical American shrub spread across India’s forests, and has now invaded about 40 percent (nearly 1,54,000 sq.km.) of India’s tiger forests and a whopping 3,00,000 sq. km. of non-tiger habitats. Why is lantana so dreaded? It aggressively competes for space and resources, pushing out native plants, leaving fewer plants for wild herbivores to feed on. Feeding on it also causes allergies and even extreme symptoms such as diarrhoea, liver failure and even death in animals. It skews the nutrient balance of the soil, among other effects. They are found colonising virtually everything from forests, fields, roadsides, and empty plots.

Innumerable freshwater bodies in India are choking under the influence of an alien water plant called water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), native to South America’s Amazon basin. It has been regarded as “the most successful colonizers in the plant kingdom”. Water hyacinth too arrived in India as an ornamental plant, and is believed to have been gifted to India by Lady Hastings, the wife of First British Governor-General, in the late 18th century. Today, dense mats of water hyacinth adorn the surface of most waterbodies in India, obstructing oxygen and sunlight from reaching the watery depths, impacting aquatic biodiversity. They are clogging up rivers and canals and this is also affecting the rice yields and fishstocks.

Prosopis juliflora or mesquite and Parthenium hysterophporus or Congress grass are two more examples among many of other such notorious floral invaders of India’s biological habitats.

Plants aside, there are some well-studied cases of invasive animals that have stemmed from the booming pet trade in exotic animals in the country. Red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) and the suckermouth sailfin catfish (Pterygoplichthys spp.) are among the emerging invasive threats to India’s native freshwater biodiversity. Between 2018-2020 alone, more than 12,000 red-eared slider turtles were seized by custom authorities in Tamil Nadu airports that were being smuggled into India.

“Red-eared sliders are native to the southern United States and Mexico. It’s fairly easy to acquire a red-eared slider in India, for as little as Rs.100 for a small individual, thanks to uncontrolled pet trade. People buy turtles as pets often without realising how big they can get or how much money goes into their maintenance. An adult red-eared slider can grow up to 30 cm. and that is a very large turtle to keep in a home aquarium. More often than not, people end up releasing pet turtles in the wild without realising the implications of releasing an invasive species in a habitat where it doesn’t belong. In India, these red-eared sliders are aggressively outcompeting native species of freshwater turtles across innumerable waterbodies for food, nesting, and basking space. They also are host to many pathogens and thus act as vectors in spreading diseases to the native turtle and other aquatic species,” explains Sneha Dharwadkar, wildlife biologist and co-founder of Freshwater Turtles & Tortoises of India (FTTI)

The southern Indian state of Kerala has become an epicentre of aquatic invasion of alien species in the country. A recent study revealed that Kerala’s waters harbour 28 alien fish species including Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) and African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and four alien aquatic weeds, which were introduced for the purposes of “aquaculture, aquarium trade, biocontrol of mosquitoes, and game fishing.”

The Indian flapshell turtle (Lissemys punctata) is one of the native freshwater turtle species found in India that has to contend with the grave problem of the red-eared slider invasives. Photo credit: Rahul Kulkarni

It is not just India. Globally, the problem of invasives has direly impacted biodiversity, ecosystems and livelihoods. Not even the elusive and inhospitable environs of Antarctica have been spared the onslaught of invasive species. And human-induced climate change is only making matters worse.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

- India’s Burning Exotic Pet Trade Crisis

- India’s Growing Fetish for Wildlife Of The Exotic Kind

- Of Alien Origins And Earthly Splendour

- Baby Turtles in Floating Rainforests

- Amputees of the Anthropocene