The slender, bony-white trunks of dhavda trees, standing out against their dark-barked neighbours, appeared unusually mottled. As the GPS guided us towards the centre of the survey grid, we found ourselves in the midst of a deafening chorus. The dark mottles on the pale trunks weren’t flakes of the barks, but cicadas. Hundreds of them, all males, buckling and unbuckling their torso muscles to blare out their love songs. We were on a forest trail in the Bawanthadi forest block in Maharashtra. From predatory robber flies to tiger and leopard scats, there were clear signs that this was a healthy forest, though not a ‘Protected Area’ with a national park or wildlife sanctuary tag. And that was exactly why we were there, with camera traps, mapping devices and other paraphernalia.

Apart from facilitating gene flow across the tiger reserves, forest corridors in Central India also support resident populations of tigers. Photo: Wildlife Conservation Trust

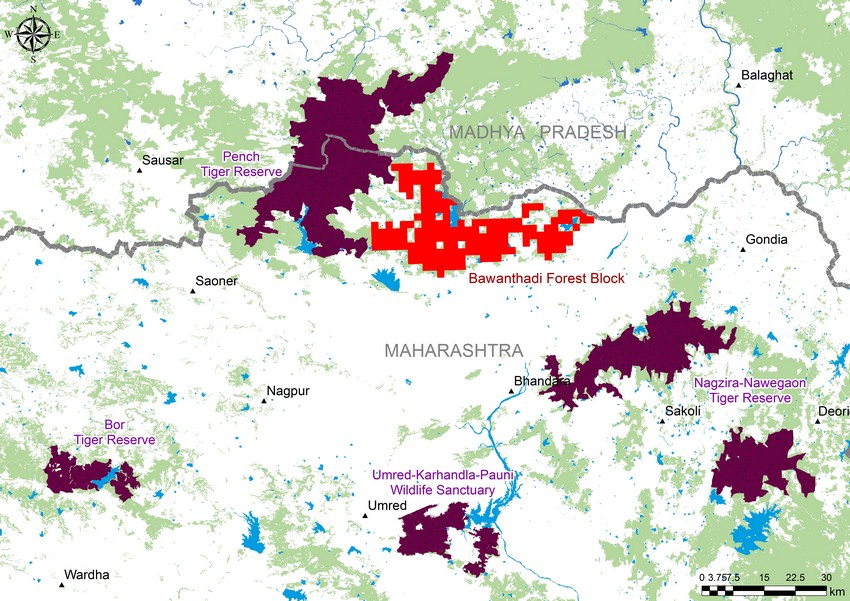

The Bawanthadi forest block, spread across the Nagpur and Bhandara Forest Divisions, spans across 600 sq. km. Vast swathes of this deciduous forest harbour a staggering diversity of insects, birds and mammals. But what makes Bawanthadi all-important is its location – the block forms a vital corridor connecting the Pench (across Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh) and Nagzira- Nawegaon Tiger Reserves. Genetic evidence and photographic records of tiger dispersal across the two tiger reserves have demonstrated that the corridor is functional, making it a high priority site for long-term monitoring and conservation.

The importance of forest corridors

Forest corridors like the Bawanthadi block are crucial to the survival of the tiger as a species. Most of the Protected Areas (PAs) in India are too small, and don’t harbour tiger populations that are ecologically, demographically and genetically viable in the long term. As tiger populations in PAs increase and coming-of-age individuals set off to find mates and establish territories, corridors enable their immigration and emigration. Past study conducted by one of the authors using landscape genetics and remote sensing has conclusively proved that tigers disperse over distances as long as 600 km., underscoring the need to conserve corridors and adopt a landscape-scale approach to conservation. This is all the more important in the Central Indian Landscape, home to 30 per cent of India’s wild tigers, where none of the tiger populations are genetically viable on their own.

The Tiger Task Force, in its first report (the original blueprint of Project Tiger) submitted in August 1972, was conscious “that maintaining a genetically viable population of tigers would require larger areas than the reserves and their contiguous forests provided.”

Apart from facilitating gene flow across the tiger reserves, long-term data also confirms that Bawanthadi supports a resident population of tigers. The Wildlife Conservation Trust’s (WCT) monitoring efforts, using camera traps, have also thrown up some pleasant surprises. Despite anthropogenic pressures, the forest is home to elusive mammals including honey badgers, Indian wolves, striped hyaenas, and rusty-spotted cats – the smallest of all wild cats.

Despite anthropogenic pressures, forest corridors harbour elusive mammals such as the rusty-spotted cat – the smallest of all wild cats. Photo: Wildlife Conservation Trust

Bawanthadi is, of course, just one of many such forest blocks across Central India that are surveyed under WCT’s Large Carnivore Monitoring Programme. We focus on gathering baseline data from multiple-use forest blocks connecting major tiger bearing PAs, as these could harbour resident populations of tigers and other wildlife. Long-term monitoring is critical to our understanding of population and distribution trends of large carnivores in these forest blocks that are part of the larger human-influenced forest mosaic in Central India. Without such data, taking informed conservation decisions and planning for landscape-scale conservation of large carnivores and their habitats are well-nigh impossible.

In India, tiger conservation efforts have largely been focused on PAs; but significant tiger populations exist outside these supposedly inviolate reserves too, and their survival here is threatened by habitat and prey depletion at the hands of humanity. “Science-based conservation is vital; we first need to know what is happening to the tiger population outside PAs. Without taking stock, we will never know what we really stand to lose when large chunks of forests get denotified for development projects,” suggests our colleague and wildlife biologist Vivek Tumsare.

What makes Bawanthadi all-important is its spatial location – the block forms a vital corridor connecting the Pench (across Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh) and Nagzira-Nawegaon Tiger Reserves.

The proposed 325 sq. km. addition to the buffer zone of the Pench Tiger Reserve, if brought into effect, would bring a prime tiger breeding site under the protective ambit of the tiger reserve. Photo: Wildlife Conservation Trust

Long-term monitoring

Monitoring efforts outside PAs yield additional insights too. Camera traps set up for wildlife also capture humans, cattle and domestic dogs. This helps assess the extent of anthropogenic pressures on the forests. Analysis of scats (faecal samples) reveals information on the diet of large carnivores, which in turn indicates the presence or absence of prey species, and the extent of the carnivores’ dependence on cattle and other livestock.

Analysis of scat (faecal samples) reveals vital information about the diet of large carnivores, which indicates the presence or absence of prey species in the area, and the carnivores’ dependence on cattle and other livestock. Photo: Aditya Joshi

Continuous, intensive monitoring over an extended period provides information on resident individuals, changes in the distribution of different species, and increase or decrease in anthropogenic pressures. This helps to formulate science-based recommendations for landscape-scale conservation. Our studies suggest, for instance, that a 325 sq. km. forest patch from the larger Bawanthadi forest block, adjacent to the Pench Tiger Reserve, would be an ideal addition to the reserve’s buffer zone. This would bring a prime tiger breeding site under the protective ambit of the tiger reserve.

Every year, 10 per cent of WCT’s camera traps are lost to forest fires and theft. Images like these indicate the extent of anthropogenic pressures on forests outside Protected Areas. Photo: Wildlife Conservation Trust

Forest blocks like Bawanthadi, that link tiger reserves and facilitate gene flow, have immense potential to contribute to the conservation of the tiger and all the species that call tiger habitat home. The Tiger Task Force, in its first report (the original blueprint of Project Tiger) submitted in August 1972, was conscious “that maintaining a genetically viable population of tigers would require larger areas than the reserves and their contiguous forests provided.” Since then, the ecological situation in tigerland has become even more critical with rapid deforestation and persistent resource mismanagement.

India is currently experiencing the early stages of a climate crisis. Connecting, protecting and valuing forest corridors as bridges essential to the survival of wildlife is one of the practical, tried and tested ways to moderate the negative impacts of climate change.

If we succeed in maintaining the linkages to the green islands of tiger reserves with healthy corridors that offer safe passage to wildlife, and also have the potential to emerge as prime conservation sites, the storm clouds of extinction just might disappear.

This article was first published in the Sanctuary Asia magazine, June 2019 issue.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the Authors: Wildlife biologist and wildlife-connectivity conservationist, Aditya Joshi heads Conservation Research at WCT, and is a member of the IUCN-WCPA Connectivity Conservation Specialist Group. Rizwan Mithawala is a Conservation Writer with WCT and a Fellow of the International League of Conservation Writers.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Disclaimer: The authors are associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Related Links

- Conservation Strategy

- Tigers: A Troubled Existence

- Connectivity Conservation

- GUARD DIARIES: Battling Forest Fires

- Wildlife Population Estimation