A trained field biologist and scientist, Dr. Anish Andheria and his team at the Wildlife Conservation Trust are currently engaged in a range of conservation initiatives in Madhya Pradesh. This article, a result of their field experience, explores the potential to secure the state’s biodiversity, so critical to our survival tomorrow, for posterity.

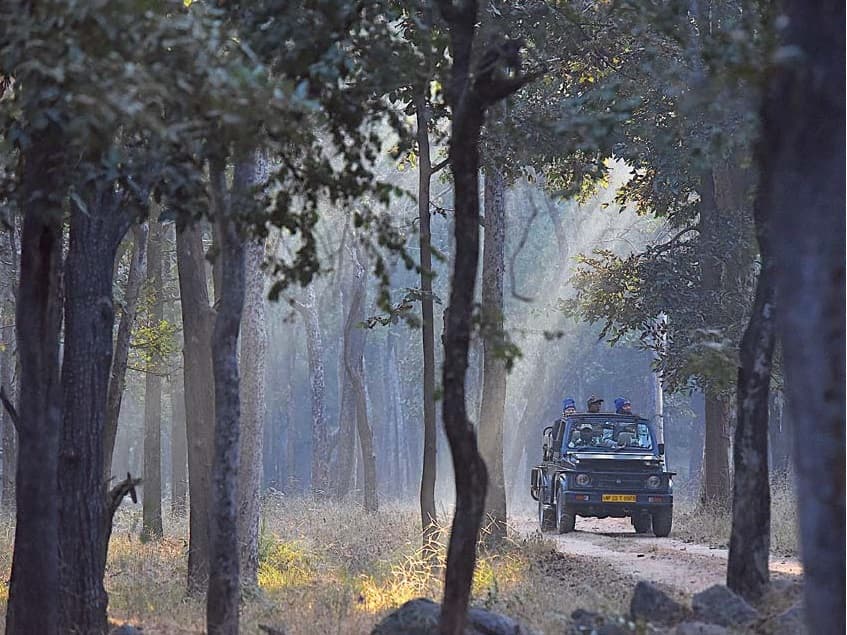

It was March 2011; our four-wheel drive veered along a sharp bend on a dirt track cutting across a restored grassland, which until 2007 was a sprawling village in the middle of the Panna Tiger Reserve. I was accompanied by R. Sreenivasa Murthy, Panna’s Field Director, and we were pleasantly surprised to see a handsome male leopard that had brought down a feral cow earlier. The seemingly nonchalant leopard had returned for a second helping. Ignoring our presence, it began feeding on the inner thigh of the cow. In the absence of tigers, leopards are known to behave like their larger cousins – fearless and relaxed.

As I put this piece together, it is 2018 and Panna has become a roaring success story, with the tiger population crossing 40 and several young individuals having dispersed into Territorial Forests over 100 km. away. Murthy has long been transferred but not before becoming synonymous with the resurrection of Panna after the shocking extermination of tigers in 2009. What looked like a hopeless situation for both tigers and Panna back then, was transformed into an exemplary case study in the field of conservation. While the resurgence is impressive, it was not brought about by a miracle. In fact, it was about doing simple things – foot patrolling, wildlife monitoring, intelligence gathering and enabling voluntary relocation of people – consistently. This aspect gives me hope that if genuine efforts are invested, we can recover most of India’s degraded forests and wildlife populations both inside and outside Protected Areas. India has enough space to support over 10,000 tigers, three times the current world population! Given here is a blue print of things that Madhya Pradesh (M.P.) can do to bring us closer to this dream.

Three tiger reserves in Madhya Pradesh – Kanha, Pench and Satpura – have implemented MSTrIPES – a GIS-based monitoring system that records real-time patrolling data, direct and indirect evidences of large carnivores and, more importantly, human disturbances.

M.P. has successfully managed to safeguard its most critical tiger habitats over the past 45 years and is an exemplar for other states wishing to secure the future of its tiger-bearing forests. Of India’s existing 50 tiger reserves, the six within M.P. have some of the most secure tiger populations on the planet. Kanha, Pench, Panna and Satpura now feature in the list of India’s 15 finest tiger reserves.

The geographical area of the state is 308,252 sq. km. of which 94,690 sq. km., is classified as ‘forest’. This landmass representing around 12.5 per cent of India’s total forest area harbours some of the world’s most precious biodiversity. Seen through a different prism, the state’s per capita forest area works out to 2,400 sq. m. as against the national average of 700 sq. m. This may sound heartening but pure statistics reveal an incomplete story.

We need to know what has happened to the state’s forest cover over the past few decades, and what current threats these fabled forests and their wildlife face. Such exploration involves issues surrounding the aspirational development demands of people, concerning transportation, power and livelihoods. Additionally, and critically, we need to anticipate how climate change will impact weather, soil moisture content, intensity of forest fires, flowering, fruiting, bird nesting and river systems in the years ahead.

Clearly, we cannot delve into such vast issues in great detail here, but the issues must be flagged to understand how we can protect, regenerate, estimate and profit from M.P.’s famed natural capital. On the following pages I argue that there is an umbilical cord between ecological sanctity and economic security.

Hidden Green Truth

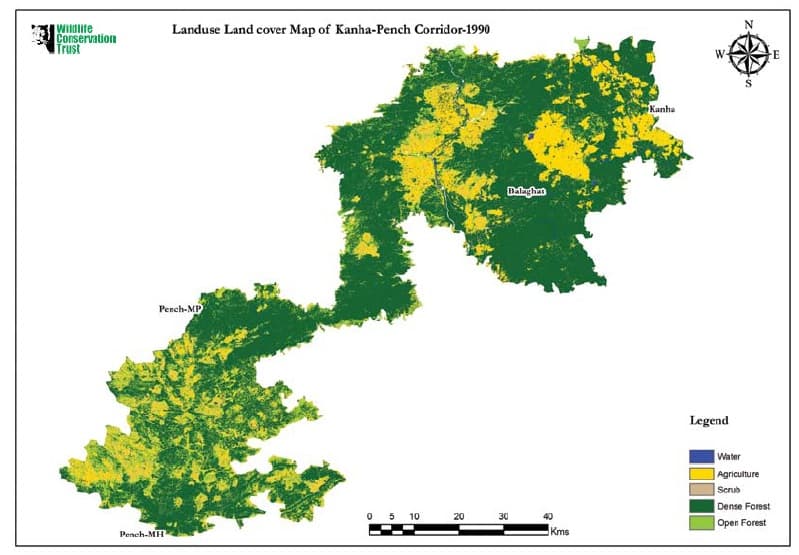

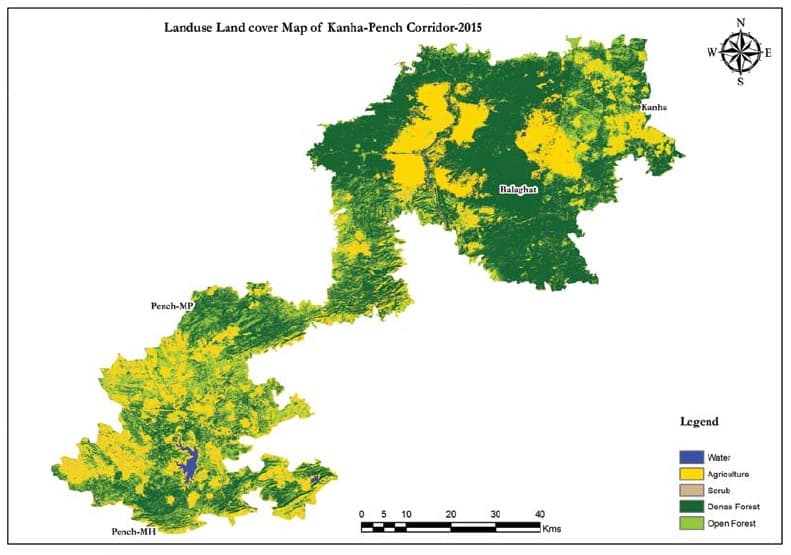

India’s ‘State of Forest Report, 2017’, suggests that a mere 12 sq. km. of forest cover was lost in M.P. in the past year. But statistics is a matter of interpretation. A realistic diagnosis is only possible by examining the fate of the three broad forest types – Very Dense Forest (VDF), 6,563 sq. km., Moderately Dense Forest (MDF), 34,571 sq. km. and Open Forest (OF) 36,280 sq. km.

Between 2016 and 2017, 23 sq. km. of VDF turned into MDF. Simultaneously, 266 sq. km. of MDF, an area the size of Bhopal, was converted to Open Forest and an equally large chunk of Open Forest was reduced to degraded forest or scrub, effectively reducing its ability to deliver the ecological services it once did.

By now the role of trees in mitigating climate change, creating and protecting topsoil, and supporting biodiversity is well understood. As each forest type moves lower down the ladder, its productivity drops, including its ability to sequester carbon. In the process, the topsoil micro-flora and fauna so critical to storing carbon and enabling the germination of seeds is also degraded. All this renders ecosystems more vulnerable to extreme weather events and this results in more frequent and more intense floods and drought. Eventually, the carrying capacity of the forest is impacted and conflicts between people and wildlife is exacerbated.

Given the way that tourism is expanding across India and the world, it stands to reason that it could prove to be a critical factor in improving the life of the people of Madhya Pradesh, who could aggregate and restore their own lands to forest status and run well-appointed homestays on nature conservancies that would be magnets for the spillover biodiversity from nearby sanctuaries and national parks.

What threats do forests face?

At one time, the principal threat to forests came from anthropogenic impacts including firewood collection, livestock grazing, hunting for bush meat and man-caused forest fires. Today, these pressures compete with linear infrastructure projects that dissect vital corridors. Additionally, with the global trade in wild animal parts growing exponentially, the poaching of endangered animals such as tigers, leopards, and pangolins, especially in Territorial Forests combines with revenge killings of wild herbivores and carnivores for crop and livestock depredation respectively. Electrocution through the illegal tapping of power lines is now commonplace. And the combined impact of all these continuing problems is compounded by the play of climate change, which alters temperature, humidity and precipitation in ways that science is only just beginning to unravel.

Food security and climate change

Agriculture, which totals roughly onefourth of M.P’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP), gainfully employs around 70 per cent of the state’s population, largely dependent on rain-fed rivers. With several rivers including the Narmada, Chambal, Shipra, Sindh, Wardha, Son, Ken, Tawa, Betwa, Tapti, Godavari, Pench, and a host of tributaries, M.P. went forward with several large dam projects. But water stress, if anything, keeps increasing. Engineering solutions to such problems have thus far involved building more dams and reservoirs for power generation and irrigation.

Increasingly, we see that new dams do not guarantee food security. In fact, a whole new breed of economists now suggest that water and food security are almost wholly dependent on ecological stability, which in turn can only be assured by restoring health to biodiverse grasslands, wetlands, rivers, lakes and forests.

The solution we need is staring us in the face. If we wish to shore up food security, we must start by making soil fertility and reliable water availability the cornerstone of public policy. The collateral benefit of such an objective would be tourism on a scale that could change the very face of M.P., even as it creates right livelihoods and enhances the state’s brand equity.

These are also the very assets upon which tourism thrives. Millions of people flock to such wildernesses from across India and the globe and economists confirm that investments in tourism are probably capable of generating more self-supporting livelihoods than any other manufacturing or service industry.

With climate change moving into higher gear, clearly M.P. needs to find ways to solve multiple problems with a common, practical solution. This is where a combination of rewilding ecosystems while creating experiential tourism, dignified livelihoods and stabilising the climate come in. Put another way, the solution we need is staring us in the face. If we wish to shore up food security, we must start by making soil fertility and reliable water availability the cornerstone of public policy. The collateral benefit of such an objective would be tourism on a scale that could change the very face of M.P., even as it creates sustainable livelihoods and enhances the state’s brand equity.

Unbridled Livestock – A Zero Sum Game

When droughts strike, people’s livestock starve, and are often released into forests. At this time, even land-owning farmers often seek sustenance through daily labour on the few productive farms with access to water. Understandably, this triggers large-scale deforestation as communities turn towards Protected Areas (PAs) for food, fodder, fuel and water. In early 2000, eastern M.P. witnessed a bad monsoon. In 2008-09, the drought expanded towards the west region and 21 districts experienced a severe rainfall deficit including Chindwara, Dewas, Harda, Hoshangabad, Sehore, Khargone and Panna.

Fodder costs rose 25 times making it more expensive than wheat! Predictably, livestock deaths rose dramatically. And destitute people began to move towards forests, which suffered even more degradation.

Voluntary Resettlement Programme

The M.P. government managed to successfully tackle some of the degradation issues through voluntary village resettlement programmes that apart from creating inviolate spaces for wildlife, ensured that communities had greater access to better livelihood options, health and education. With the support of the Collectors’ offices several tiger reserves such as Satpura, Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Panna and Sanjay-Dubri have benefited from the village resettlement programme. In a first of its kind initiative, the M.P. government went on to offer the resettlement package even to villages in corridors such as the Balaghat Forest Division. This will go a long way in reducing conflict in the years to come.

Despite traditional differences between social activists and wildlife managers, the truth is that in the long run, securing forests will revive the catchment of M.P.’s rivers, which in an era of climate change can only help the of the poor by improving their food and water security.

With over 30 per cent of the state’s total geographical area clothed in forests, it fares better on this index than Gujarat, Maharashtra and Telangana. However, it’s the quality of the forest we must work on if real solutions on the ground are to be implemented.

While the voluntary resettlement programme will definitely have a net positive impact on the ecosystem services provided by forests, it is by no means a magic wand that can resuscitate forests in isolation. This is why there is a need to safeguard existing biodiverse inviolate areas from proposed large dams and river-linking projects. One conflicted issue is that of the Ken-Betwa river-linking project. Community leaders justifiably ask why they should be displaced to create inviolate wildernesses, when the government itself seeks to destroy the most biodiverse forests such as the Panna Tiger Reserve under reservoir submergence?

In the case of the Panna Tiger Reserve, the argument is particularly strong since the State Forest Department performed a near-miracle within a span of eight years by reestablishing a robust tiger population after the unfortunate local extinction episode of 2009. What is more, by destroying the forests that feed pure water into the Ken river there can be no hope of ‘exporting’ surplus water from this basin to another.

Rewilding the state

Rewilding: With over 30 per cent of the state’s total geographical area clothed in forests, it fares better on this index than Gujarat, Maharashtra and Telangana. But as mentioned earlier, it’s the quality of the forest we must work on if real solutions on the ground are to be implemented. And fortunately, we know the steps that need to be taken to achieve this.

Clearly, the first step lies in protecting zealously every last vestige of natural ecosystem, for it is only from this germplasm that natural regeneration will spring. To a large extent, this objective has been achieved inside the core areas of M.P.’s best biodiversity vaults. It is time, therefore, that the same practices be introduced into the buffer zones of tiger reserves and in reserve forests that form part of vital wildlife corridors. Old-fashioned strategies of ‘tree-planting’ will not work. What needs to be done is what H.S. Panwar, the first Director of the Kanha Tiger Reserve, insisted on, namely to provide jobs to neighbouring village communities for rewilding. In exchange the villagers could be persuaded not to graze their cattle in forests and not to trigger forest fires either. This last point is more important than most imagine. In the past decade, something like 70 per cent of all Territorial Forests have burned each year during the tendu and mahua collection seasons. Often fires are started to catalyse fresh green growth used as fodder in late winter.

It is time we called a national halt to forest fragmentation, which could undermine all of India’s climate commitments if deforestation continues apace…. more than increased density of wildlife, it is deforestation and fragmentation that causes human-wildlife conflict.

Roads, rail, transmission lines and canals: It is time we called a national halt to forest fragmentation, which could undermine all of India’s climate commitments if deforestation continues apace. Linear infrastructures need not cut through Protected Areas or eco-sensitive zones. As in the case of by-passes that skirt towns, such infrastructures must be aligned away from biodiverse areas, or perhaps designed to run subsurface to minimise adverse impacts on wildlife. Where existing linear infrastructure needs expansion and when all other options such as realignment are unviable, mitigation measures should be suggested, so as to minimise impact on the movement of wildlife. Such mitigation structures should consider the interest of both large mammals and small animals including reptiles and amphibians.

Mud on Boots: Virtually no on-ground protection works better than forest patrols that are systematic, well-designed and regularly monitored. This involves systematic patrolling by guards and watchers not merely in tiger reserves, but also buffers and corridors. Three tiger reserves in the state – Kanha, Pench and Satpura – have implemented MSTrIPES – a GISbased monitoring system that records real-time patrolling data, direct and indirect evidences of large carnivores and, more importantly, human disturbances. GPS data is collected daily, collated from all the ranges, analysed and diligently shared with the park management every 15 days. This enables the Field Director to make informed decisions about increasing vigilance or taking corrective measures in a particular area, all based on hard data from the field. If M.P. extends these monitoring protocols to other PAs and corridors, the result will undoubtedly be reduced poaching and forest degradation.

Naturally all this requires statewide field-training involving all beat guards and watchers, preferably in collaboration with carefully-chosen village youth from farming families. Such steps would also prevent miscreants from tapping power lines to electrocute animals. The death toll from such a practice includes everything from mongooses, small cats, civets, jackals, large herbivores, and carnivores to small animals such as scorpions and snakes.

Human-wildlife conflict resolution: More than increased density of wildlife, it is deforestation and fragmentation that escalates humanwildlife interactions, which over time can transform into conflict. Simply put, when food that wild animals depend on dwindles, species are forced by hunger to turn to crops and livestock, intensifying the losses incurred by local communities.

Of all the states in India, M.P. probably has the best veterinary staff affiliated to tiger reserves, equipped with state-of-the-art rescue trucks in each reserve. It is critical that the same quality of rescue teams and infrastructure be made available in Territorial Forests where most human-animal conflicts take place. Each rapid response team will need trained staff to maintain a high level of efficiency and motivation.

When communications between forest staff and people break down, overreaction to the mere sight of a large carnivore close to a village or agricultural field can create problems where none exists. Predictably this takes a toll on people-park relationships, often prompting people to take the law into their own hands. This includes killing herbivores and carnivores, which in turn sets off a domino effect that feeds the illegal wildlife trade. The adverse domino effects do not end here. A drop in herbivore density in territorial areas forces large carnivores to turn to livestock. If such basic issues remain unaddressed, or if the response time in dealing with acute wildlife conflicts is too long, all other community-based conservation programmes are destined to fail. Sometimes local politics comes into play, with communities being unnecessarily instigated against hapless forest staff.

Of all the states in India, M.P. probably has the best veterinary staff affiliated to tiger reserves, equipped with state-of-the-art rescue trucks in each reserve. It is critical that the same quality of rescue teams and infrastructure be made available in Territorial Forests where most human-animal conflicts take place. Each rapid response team will need trained staff to maintain a high level of efficiency and motivation. Training in crowd control will be of utmost importance. If people can be stopped from gathering in large numbers when a carnivore enters a human settlement, half of the problem is solved. If left alone, more often than not, a wild animal will make Of all the states in India, M.P. probably has the best veterinary staff affiliated to tiger reserves, equipped with state-of-the-art rescue trucks in each reserve. It is critical that the same quality of rescue teams and infrastructure be made available in Territorial Forests where most human-animal conflicts take place. Each rapid response team will need trained staff to maintain a high level of efficiency and motivation. its way back into its familiar forest. We also have the issue of losses due to crop damage, or predation of livestock. When farmers are not promptly and fairly compensated, resentment grows. Sullen villagers are more easily recruited by poaching gangs. A combination of all the above, implemented by sensitive, sensible forest officials in consultation with village opinion leaders is the only real way forward.

Forensics laboratories and skill development: Wildlife crime cannot be effectively curbed unless it is recognised as a social evil with the capacity to destabilise both our social and ecological foundations. A revolving door exists between the operatives involved in the global illegal trade in wildlife, arms, narcotics and human trafficking. One often finances the other. Which is why M.P. needs state-of-the-art forensics laboratories to study cases and rapidly gather evidence that can lead to convictions in courts. Such labs can also help with DNA analyses to positively identify carnivores responsible for human attacks, which would avoid the capture or killing of an innocent tiger or leopard, which often takes place today. Currently samples must be sent to the ‘Laboratory for the Conservation of Endangered Species’ (LaCONES) in Hyderabad, or to the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, where the turn-around time for analysis is excruciatingly long, often as long as three months. This hardly helps prosecuting lawyers to nail poachers, or the rapid identification of a renegade carnivore terrorising a village.

The total carbon stock of forests of Madhya Pradesh is about 396 million tonnes of carbon, equivalent to about 2,551 million tonnes of carbon dioxide – amounting to nearly 10 per cent of the total forest carbon of the country. This can be doubled even if 50 per cent of the subsistence farmers move from depredation-prone traditional crops to agroforestry.

Protecting endangered species: Every species has its own special ecological imperatives. While overall ecosystem protection is the umbrella objective, within large landscapes it is vital that parcels of habitats are so managed as to benefit endangered species such as gharials, Eurasian otters, Indian pangolins, wolves, hyaenas, caracals, four-horned antelopes, cave-dwelling bats, Indian and White-rumped Vultures, Forest Owlets, Sociable Lapwings, Great Indian Bustards and more, many of which are to be found outside iconic tiger reserves. In the haste to somehow benefit Panthera tigris, many unnoticed, little-understood, yet crucial species have been negatively impacted in the past. It is time to undo some of this.

In saving the tiger, a host of lesser seen lifeforms find security. Seen here is an Indian rock python Python molurus (left) and a six-spotted ground beetle Anthia sexguttata (right). Both are as vital to the integrity of the ecosystem as their more charismatic co-inhabitant.

Managing Reserve Forests for biodiversity: One of the critical survival challenges for the Indian subcontinent and its growing economy is how to guarantee ecological stability, while simultaneously satisfying the aspirations of people in search of a better life. Probably the most inexpensive and effective way to do this would be to safeguard healthy forests and regenerate degraded ones. Towards this end, M.P. is likely to be a leader by upgrading some of its Territorial Forests to national park or wildlife sanctuary status.

On top of the list of such potential upgradations are Kalibheet, Omkareshwar, Gandhi Sagar, Amarkantak and Kuno-Palpur, the first four are largely Reserve Forests, and the last one a wildlife sanctuary. The Kalibheet forest is located north of the Melghat Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra and has the capacity to accommodate significantly larger wildlife populations if adequate protection is provided.

Some time ago, the Narmada Sagar Project led to the destruction of 411 sq. km. of forest on account of submergence or diversion. To compensate for the damage the National Board for Wildlife stipulated that an equivalent size of Reserve Forest be upgraded to PA status. An Expert Committee comprising scientists recommended that an area of 759 sq. km. be given national park or sanctuary status, but this was resisted and finally reduced to 511 sq. km., constituting the Omkareshwar National Park (250 sq. km.), Surmanya Wildlife Sanctuary (187 sq. km.) and Mandhata Wildlife Sanctuary (66 sq. km.). But no action was taken. Yet another survey, this time an aerial one, was carried out in 2006 and a fresh set of recommendations made, in which, the recommended PA sizes were 642 sq. km. constituting Omkareshwar National Park (246 sq. km.); Singaji Wildlife Sanctuary (177 sq. km.); Mandhata Wildlife Sanctuary (68 sq. km.); Narmada Conservation Reserve Unit-I (131 sq. km.) and Narmada Conservation Reserve Unit-II (19 sq. km.).

As many as 12 years have passed, but these areas have not been notified yet. But recent indications suggest that the M.P. Forest Department is preparing a case to demonstrate that apart from ‘compensating’ for past forest losses, the regeneration of these forests, which feed the Narmada river, would greatly enhance the productivity and the water security of the Indira Sagar Dam. The immediate benefit would be enhanced lean-season flows of water and reduced siltation loads in the reservoir.

Without a shadow of doubt the resultant increase in biodiversity including birds, would dramatically enhance the capacity of M.P to accommodate more visitors and thus boost tourism and state revenues. Each year of delay, however results in progressive degradation. From some of these forests tigers and gaur have vanished and the density of leopards and hyaenas have gone down too.

Through this book the connection between forests and rivers is repeatedly evident. Amarkantak, for instance is the birth place of both Son and Narmada rivers, and is connected to Kanha through the Phen Wildlife Sanctuary and also directly to the Achanakmar Tiger Reserve in Chhattisgarh. These forested areas cry out for increased level of protection. And it would be so easy to work with nature’s incredible self-recovery systems to re-establish the lost connectivity between Bandhavgarh and Amarkantak provided planners and decision-makers see the clear-as-day economic self-interest for the state and its people.

The same holds true for the regenerative capacity of the forests of Gandhi sagar and the adjoining regions of Mandsaur and Neemach, primarily forests that line both sides of river Chambal. If a wildlife sanctuary was declared here the movement of tigers between Gandhi sagar in M.P. and the Mukandra Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan could take place seamlessly.

It is also time that Kuno was upgraded from sanctuary to national park status. As of now the 345 sq. km. Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary is inviolate, with a buffer of roughly 924 sq. km. By voluntarily resettling just one village from its vicinity, the total inviolate forest area would expand to 900 sq. km., thus spectacularly improving the ecological status and the carrying capacity of the entire landscape for wildlife. Interestingly, Kuno is already a home for tigers migrating across the Chambal river from the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve, Rajasthan, which lies at a distance of around 50 km. as the crow flies.

Turning failed and marginal farms back to forests: As in the rest of India, so in M.P., nonforest lands (which were once well forested) are being used primarily for subsistence agriculture. As recent history has shown, the status of such subsistence farming families is far from satisfactory and ways must be found to guarantee them with better health, education and nutrition, even as expanding human populations are able to obtain dignified jobs.

Given the way that tourism is expanding across India and the world, it stands to reason that it could prove to be a critical factor in improving the lives of the people of M.P., who could aggregate and restore their own lands to forest status and run well-appointed homestays on nature conservancies that would be magnets for the spillover biodiversity from nearby sanctuaries and national parks.

This would have the collateral benefit of enhancing forest cover, while sequestering atmospheric carbon. Today, in 2018, India is predominantly an agrarian society, with between 65 to 70 per cent of our people sustaining themselves from farming. But 85 per cent of farm holdings are under two hectares, which basically means most are subsistence farmers. With advancing climate change the sustainability of their farms in the days to come is likely to become less reliable.

The advances in science, the clarity regarding the negative impact of climate change if punitive measures are delayed, and the increased understanding of ecosystem services have highlighted the importance of prioritising natural capital over man-made assets, especially in the context of a densely-populated nation like India.

On top of this, farmers are forced to deal with crop depredation, not only from herbivores, birds and other wild animals, but also from beetles, grasshoppers and fungus attacks aggravated by changing humidity and temperatures. The tragic consequence of such hardships have rocked our nation with, by some estimates, one farmer committing suicide every eight hours in 2016 in M.P. alone. We have the power to reverse this tragedy.

According to the State of Forest Report, 2017, the total carbon stock of the forests of M.P. is about 396 million tonnes of carbon, equivalent to about 2,551 million tonnes of carbon dioxide – amounting to nearly 10 per cent of the total forest carbon of the country. This can be doubled even if 50 per cent of the subsistence farmers move from depredationprone traditional crops to agroforestry. Such a move can have multiple benefits such as drastic reduction in crop-depredation; increase in forest cover; improvement in the quality of corridors; growth in biodiversity; augmentation of income of farmers through wildlife tourismbased vocations; reduction of pollutants such as pesticides and fertilisers; sequestration of a much larger amount of atmospheric carbon and most importantly, reduction in time invested in guarding the fields from wild herbivores – this extra time could be utilised to develop newer skills, thereby creating an alternate income source for villagers.

Now or Never

As we have seen, every problem comes bundled with multiple solutions. The advances in science, the clarity regarding the negative impact of climate change if punitive measures are delayed, and the increased understanding of ecosystem services have highlighted the importance of prioritising natural capital over man-made assets, especially in the context of a densely-populated nation like India. Ironically, history has witnessed government after government liquidating natural wealth (forests, soil, mountains, air, rivers, and wildlife), for short-term, diminishing returns. A relatively high percentage of forest compared to several Indian states is a testimony to the natural and cultural legacy of M.P. However, it is clear from preceding paragraphs that the state’s glorious past is no insulation against the impending problems of forest degradation and climate change, leading to collapsing ecosystems. Several states that have lost most of their old-growth forests will find it extremely challenging to cope with the cascading effects of indiscriminate environmental destruction; however, M.P. still has the option of choosing an energy efficient pathway towards development. Whether political will allows common sense to prevail, only time will tell.

This article was first published in the book ‘Wild Madhya Pradesh’, a Sanctuary publication.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the Author: President of the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), which is involved in projects across central India, Dr. Anish Andheria’s focus research area has been predator-prey relationships. An accomplished naturalist and wildlife photographer, he has authored several scientific papers and books.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Disclaimer: The authors is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Related Links

- The Lions’ Last Walk

- Meet Dr. Anish Andheria – Scientist, Naturalist, Conservationist, Photographer

- USAID

- H.T. Parekh Foundation

- Wildlife Week – We Are All In This Together