The concept of wildlife corridors though astonishingly simple in principle, has a cloud of ambiguity hanging over it when it comes to defining it, especially in legal and policy terms. It is plain and simple that myriad species need to physically move across their natural range for breeding, migrating and feeding. To maintain healthy genetic diversity and avoid inbreeding, disparate wildlife populations need to stay geographically connected for the genes and other natural processes to flow.

The function and form of a corridor differs from species to species. Say for example, a young male tiger may use a corridor to disperse onto newer territory, a herd of elephants may use a suitable patch of forest as a corridor regularly as it falls along its ancient migratory route, while a group of arboreal hoolock gibbons may use the tall trees along a corridor as a highway to get to the other side of the forest to feed. The undisputed fact remains that without unhindered physical connectivity, long term survival of wildlife populations is heavily jeopardised.

So what is a wildlife corridor? In simple terms, a corridor is a relatively narrow strip of any natural habitat, such as forest, that has managed to survive and is still suitable for wild animals to use and move between two or more larger forest blocks. These corridors keep forests from turning into isolated islands of biodiversity amidst a sea of human habitation, agriculture, mines, roads, railways, canals, industries and other infrastructure.

Schrödinger’s Cat Paradox: Legal Protection for Corridors in India a Myth and a Reality?

Considering how crucial wildlife corridors are to conservation, it is ironic how little they are understood, respected, and protected. Lately, geographic connectivity of wild habitats is being increasingly prioritised globally. Significance of habitat connectivity, not just for wildlife movement, but also for healthy functioning of ecosystems, is scientifically well established. But, in India, corridors languish from extreme degradation and apathy. Under the Indian law, wildlife corridors are not explicitly defined or protected along the lines of tiger reserves and national parks. But, they are not completely devoid of legal protection either. Forest protection rules and guidelines under government agencies such as the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) and National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) can be favourably invoked to make a good case for corridor protection and seek legal provisions. Favourable judicial judgements have been passed in favour of the corridors in the past, but much more needs to be done.

Thirty-two major tiger corridors were mapped by the NTCA and WII in 2019 across four important Indian landscapes including the Western Ghats, and Shivalik Hills and Gangetic Plains, legally bestowing more resources for better management of human-wildlife interactions as well as improved protection of these corridors from infrastructure development projects and other habitat interferences, as per the Union Environment Ministry mandate. While several smaller corridors have been left out from the list, it is still a huge step towards recognising that tiger habitat outside PAs is as important as that inside. Additionally, the Tiger Conservation Plan (TCP) of every tiger reserve has to mandatorily include a chapter on corrirdors that connect that particular tiger reserve with other healthy breeding populations of tigers.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) notification, another legal tool in the environment protection arsenal that makes it mandatory to seek Environmental Clearance for various developmental projects, does help to prevent diversion of ecologically important areas, such as parts of corridor land, for non-forest uses. Though, dilution of the notification rules and loopholes with newer amendments made to the EIA notification over the years has put the country’s environmental policies under scanner.

But, protecting and managing wildlife corridors in India is a challenge of behemoth proportions in the face of complex threats and issues – social, economic, and environmental. With rising human population, the encroachment and conversion of forest in the remaining vestiges of connecting corridors is severing crucial connectivity between various Protected Areas (PAs) and other biodiversity hotspots. The sanctity of wild habitats lies in their contiguity and the resulting connectivity, but increasing fragmentation of these habitats is causing irrevocable damage to wildlife and the functioning of ecosystems.

Corridors Under Threat

It is a myth that corridors aren’t biodiversity-rich and pose as mere bridges or highways for the wildlife to pass. Research shows that tiger densities in several wildlife corridors in India are comparable to or better than that of some of the tiger reserves in the country! Also, tiger corridors serve as habitat for several other species such as wolves, hyenas, ratel, pangolins, birds, reptiles, etc.

Today, the expanding networks of roads, railway lines, power lines and canals have emerged as the dominant threat to India’s wildlife corridors. India has the unenviable distinction of possessing the second-largest road network in the world. A study by the Wildlife Conservation Trust states that though central India harbours nearly 35 percent of the country’s tiger population, not a single tiger sub-population in the region is genetically viable on it own. Thus, for their long term survival, these populations need to be able to interact with each other through immigration and emigration which is possible only through the network of wildlife corridors. But, National Highways 6 and 7 are prime examples of major linear infrastructure cutting through important PAs and corridors in central India such as the Bor-Melghat, Navegaon-Nagzira and Kanha-Pench corridors. These roads act as major barriers for animal movement and cause countless wild animal deaths due to collisions with motor vehicles. Rise in number of roadkills along these highways are undoubtedly impacting wild animal numbers in the region.

Eight-year-old Bajirao, a male tiger in Maharashtra’s Bor Tiger Reserve, was killed along the National Highway-6 after being hit by a speeding vehicle in 2017. Photo credit: Sheetal Kolhe

The following line in the aforementioned study ,“[I]n an overwhelming number of proposals for forest land diversion, the user agency denies the value of the forest as a corridor offering connectivity and the need for a clearance from the National Board for Wildlife,” clearly indicates the inefficiencies in policies that govern linear infrastructure project clearances in the country irrespective of the gravity of ecological concerns stemming from the projects’ impact and the general lack of inclination to include mitigation measures to counter the impact.

“… [t]he negative impacts of linear infrastructure are disproportionately high compared to the area diverted,” the study further states.

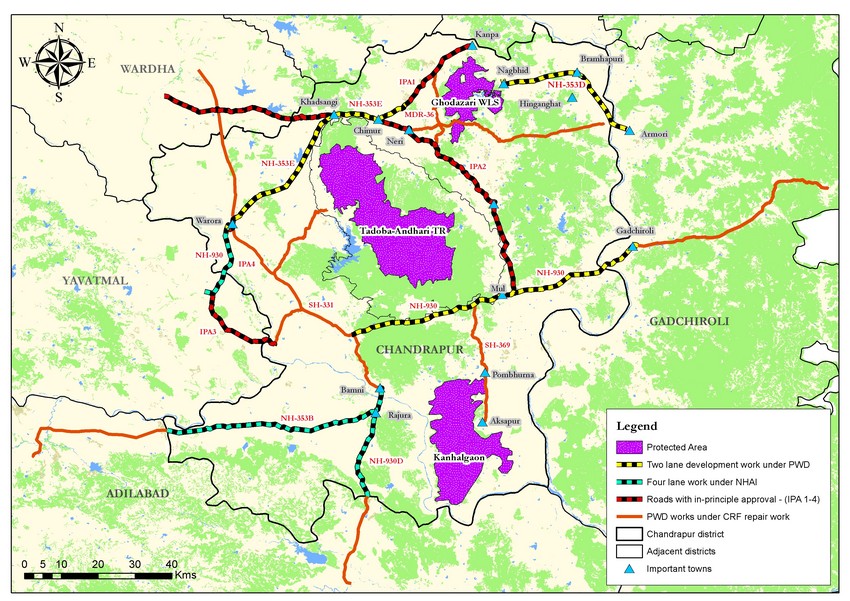

“Unfortunately, the best of last remaining wildlife habitats in central India overlap with coal reserves. Additionally, it is far more easy to quietly submerge large swathes of forest under a hydroelectric or irrigation project than an urban or semi-urban landscape. Both these reasons join hands to put insurmountable pressure on the last remaining natural capital that constitutes self-repairing natural ecosystems of India. The inaccurate or lack of cost-benefit analyses of these infrastructure projects is wrongly tilting the balance in favour of projects that take away natural, renewable capital, our only insurance cover against the threat of climate change, in exchange for short-term developmental gains. The Maharashtra State Government’s decision to build mitigation structures along newly expanded national or state highways to allow safe passage for wildlife, and ruling against giving mining leases in few coal blocks around the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve are decisions in the right direction. However, such steps need to be replicated rapidly in other states if we have to halt the decline of forests, especially along vital wildlife corridors, across the country,” observes Dr. Anish Andheria, President, Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Overview of roads in Chandrapur, Maharashtra, passing through forests and the corridors connecting Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve. Credit: WCT

Another important study, recently published by WWF-India, paints a bleak analysis of the status of the five important corridor complexes that provide significant connectivity between the Kaziranga National Park and the Karbi Anglong hills to its south in the state of Assam. The nine important corridor tracts identified within these corridor complexes provide the much needed connectivity for wildlife movement, especially during monsoon when the Brahmaputra river floods the low-lying areas of Kaziranga every year, and the animals are forced southwards where they seek high ground among the the Karbi-Anglong Hills. Using high-resolution satellite imagery and intensive ground truthing field surveys, the study has revealed that these corridor complexes are highly disturbed mosaics of patches of dense forests, open and degraded forests, tea plantations, agriculture, built-up area, mining, stone quarrying, etc. The National Highway-37 that passes between Kaziranga National Park and Karbi-Anglong hills acts as a huge barrier for wild animals and witnesses multiple roadkills each year.

Greater one-horned rhinos caught in a flood in Kaziranga National Park seek high ground in the Karbi-Anglong Hills to the south of the park. Photo courtesy of Rohit Choudhury.

Despite the nine important animal corridors having been identified by the Assam Forest Department, the state government is still to officially notify them. This delay in notification is being heavily exploited by land mafias to carry out illegal activities along these corridors, such as mining, land grabbing for building hotels, commercial activities on agricultural land, etc. This, despite the Supreme Court’s explicit order meted out in 2019 which states, “No new construction shall be permitted on private lands, which form part of the nine identified animal corridors of the Kaziranga National Park (KNP), Assam.”

“Assam Forest Department needs to take the matter of protecting the corridors and notifying the eco-sensitive zone (ESZ) around Kaziranga National Park much more seriously. Even after the Hon’ble Supreme Court’s order banning construction activities along nine identified animal corridors connecting Kaziranga National park and Karbi Anglong, the construction activity still continues unabated. It’s so unfortunate that Tiger Conservation Plan (TCP) of Kaziranga Tiger Reserve has not been finalised till date since the declaration of Kaziranga as a tiger reserve in 2007!” says RTI and environment activist, Rohit Choudhury.

A 2017 study titled ‘Right of Passage: Elephant Corridors of India’ by WTI , identified 101 elephant corridors across the country and revealed that only 12.9% of these corridors were fully under forest cover. South India hosts a comparatively large population of wild Asiatic elephants, an estimated 14,606 individuals as per the last estimation. But, the subject of elephant corridors in the region is a complex and sensitive one. Most of these corridors are either rife with the problem of elephant deaths and casualties caused due to collisions with vehicles and trains that ply on the roads/railway lines that cut through these corridors, or are hotspots of severe human-elephant conflict which is also a burning conservation issue across the rest of the elephant states in the country. Take the example of the proposed Sigur Elephant Corridor, the only elephant migration corridor in the Nilgiris that lends crucial connectivity between the Western and Eastern Ghats and allows for the movement of about 6,300 elephants moving between the states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. But, the question of legal notification of the Sigur Elephant Corridor has been a matter of intense ecological and indigenous community rights battle for years.

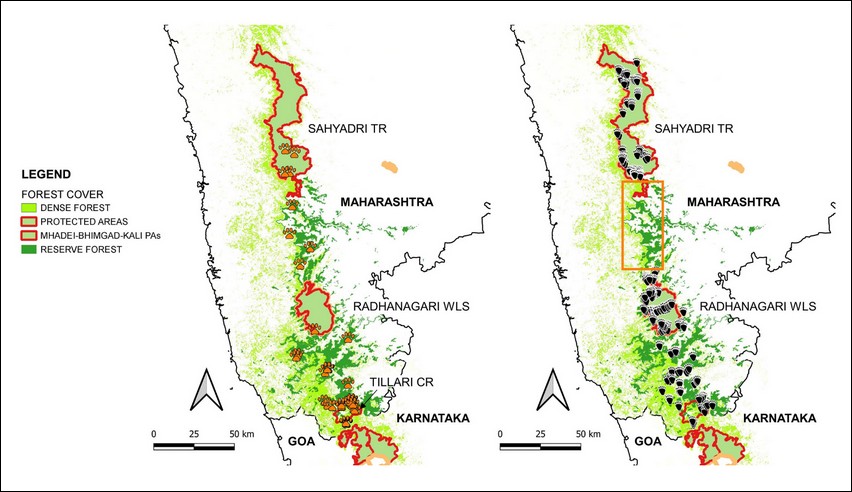

In June 2020, ~30 sq. km area of Tillari region in Maharashtra was declared a Conservation Reserve. The Tillari valley, though small, is a crucial forest fragment that offers residual bottleneck connectivity for wildlife movement in the region, especially for the movement of source population of tigers from Karnataka to Maharashtra. Part of the larger Sahyadri-Konkan corridor, Tillari poses as an important junction connecting the Western Ghats of Maharashtra to that of Goa and Karnataka. But, the land-use changes accruing in the privately-owned land around Tillari, such as replacement of forest patches with monoculture plantations of cashew and rubber is offsetting the positive ecological benefits of a protected corridor and diluting the joy of a hard-won conservation victory.

Upon looking closely at these two comparative maps of detections of tiger (left) and sloth bear (right) signs along the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor, you will notice that there are no bear signs between Sahyadri TR and Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary. This shows that the sloth bear population in Sahyadri is isolated from the population down south, indicating the species sensitivity to habitat fragmentation.

“With the notification of the Tillari Conservation Reserve, an important pinch-point was secured, but with so many private parcels of land interspersed with forest land, a threat from unfavourable land-use changes looms large. Setting up nature conservancies on these private lands which have standing forest should be the necessary end goal to protect this vital Protected Area for posterity. My studies over the last seven years in the region have revealed nine different tigers, highlighting the importance of even such small forest patches from the perspective of tiger connectivity in the northern Western Ghats,”explains Girish Punjabi, Wildlife Biologist with WCT.

“Numerous species are sensitive to the effects of fragmentation due to their limited ability to disperse through fractured landscapes. Therefore, functional corridors are crucial to protect meta-populations of multiple species, so that Protected Areas don’t turn into islands. Legal protection to these corridors is vital, otherwise isolated populations may not survive the effects of inbreeding in the long-run,” he adds.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

- Roads To Nowhere – Roadkills – A Citizen Science Initiative

- Whose Right of Way?

- Human Elephant Conflict Mitigation

- Securing the Sahyadri-Konkan Corridor