More than a forest… a miracle

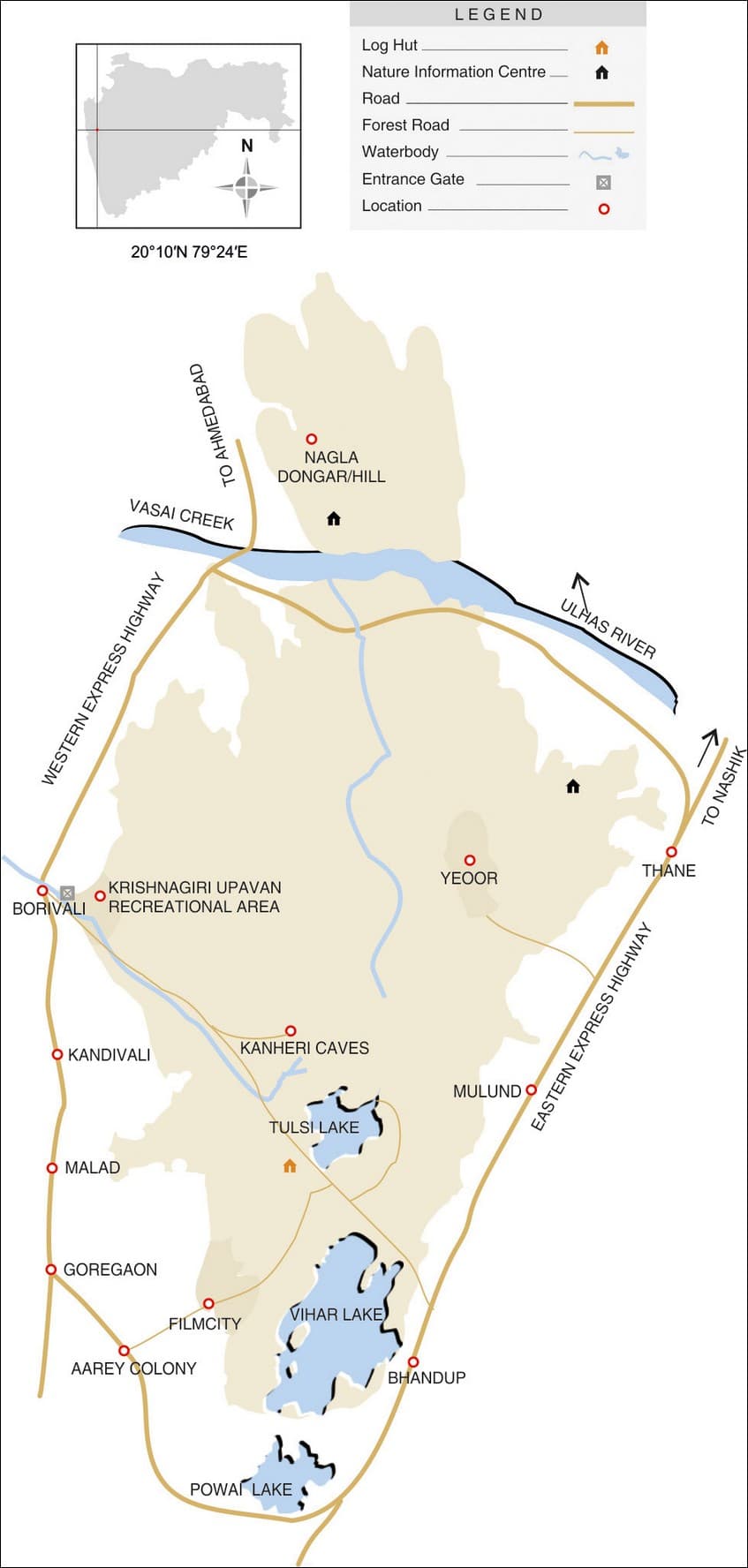

The Sanjay Gandhi National Park is a vital source of water for the city of Mumbai, with the Tulsi and Vihar lakes located within its protected confines. Dr. Anish Andheria has known this city-forest intimately for several years and writes here of its magical systems and the species that combine to make it one of the world’s most unique wilderness areas.

Sudden incessant bonnet macaque alarm calls broke the silence of an otherwise calm winter morning. “Leopard,” I whispered to my group members gesturing them to sit by the edge of the road. A couple of minutes passed, the calls continued, but no leopard appeared. Without taking my eyes off the road, I signalled to the others to be patient. Moments later a full-grown female leopard made her appearance on the road less than 50 m. from us. In typical leopard fashion, she took a couple of steps, stood, turned her head to survey her surroundings, looked straight at us, then crouched before ambling away in the opposite direction to vanish into the thick forest.

Far from some tale in Kipling’s Jungle Book, this was a routine 10-minute time capsule in a most accessible, unrivalled wilderness, located in the heart of densely-populated Mumbai.

Two views of the same area in SGNP (top) pre and post the monsoon. Each season throws up a new bout of wonders to be had in this miracle forest, many of them plants such as the crab-eyed creeper Abrus precatorius (bottom) whose seed pod has opened to broadcast its precious genes. The black-tipped scarlet seeds of this plant are poisonous but are used as decorative beads and, in bygone days, were used to weigh gold. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria

I have been on a hundred walks in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP), popularly referred to as the Borivali National Park, which has cast a spell over me ever since my first visit 25 years ago. Little did I know then that this would transmute into an incurable addiction that would rejuvenate my body and soul.

Despite its proximity to the ‘monster city’ of over 20 million inhabitants, SGNP supports an impressive conglomerate of plants and animals – over 280 species of birds, nearly 1,400 species of plants, about 40 species of mammals, 61 species of reptiles, around 14 species of amphibians, 150 species of butterflies and an immeasurable array of other invertebrates. Most famous among these are atlas and moon moths, both spectacularly beautiful and huge insects. The wingspan of the atlas moth is an impressive 30 cm.! The leaf litter is loaded with the who’s who of the invertebrate world – giant tarantulas that can make an easy meal of an unsuspecting bird, several species of trapdoor spiders that construct burrows with a cork-like trapdoor made of soil, vegetation and silk, and several unknown species of detritivores such as cockroaches, bugs, beetles, earthworms, millipedes – all working in tandem to transform plant and animal matter into highly-nutritious soil. Pagoda ants and weaver ants look for invertebrate prey on trees while harvester ants search for seeds on the forest floor. Termites, too, form an important ingredient of the fauna of SGNP. It is believed that ants and termites are so numerous, that in a tropical moist semi-evergreen forest such as SGNP, together, they weigh more than all the vertebrate species here!

The porous boundaries of SGNP have fostered a population of leopards (above) that often venture out of the park in search of dogs that breed prolifically on the mounds of edible garbage left on streets. This image was the result of camera-trapping technology used in a study that seeks to analyse the causes and extent of such conflicts. Clearly, however, SGNP’s leopards are increasingly being forced into close proximity of humans with tragic consequences for both. The more people, rich or poor, encroach into the forest, the worse the problem will get. Photo: Mumbaikars for SGNP

The most talked about animal in the park is undoubtedly the leopard. The city virtually encircles SGNP, with the Vasai creek to the north impeding the natural dispersal of leopards to the Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary and other connected forests. This and the burgeoning dog population near the park’s periphery have resulted in a larger than normal leopard population, which exacerbates human-leopard conflicts, particularly in adjoining slums and residential complexes. In the process, several leopards have been injured or killed in road accidents and many others, under public pressure, have been indiscriminately trapped by the Forest Department from housing complexes.

Without exaggeration, if SGNP dies, the city itself will start dying. And with potential climate change impacts looming large, this park, together with Tungareshwar and Tansa, are Mumbai’s insurance policy against possible evacuation at the hands of extreme weather events that could trigger severe water shortages on the one hand and floods on the other.

One needs to look outside the national park to understand the real issue. A huge tract of SGNP’s periphery continues to degrade at a rapid pace due to the pressure of tens of thousands of residents in the 20,000 or so hutments located inside and 35,000 just outside of the park boundary. And the all-powerful construction lobby shows no sign of relenting in its march to grab more forest land by bending every imaginable rule and law to build gigantic skyscrapers cheek by jowl with the leopards and their forest. All this degrades and destroys the park that is beset by quarries, tree felling and pollution. Without public support the Forest Department will be unable to protect this park that is so vital to the city’s water security.

Today, a large number of nature education groups and organisations, including the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), use SGNP to demonstrate how protecting nature ends up improving the quality of life of citizens. Children are introduced to nature by a virtual army of naturalists who are themselves motivated by the enthusiasm and wide-eyed wonder of the youngsters. And, of course, history has shown that nature is incredibly resilient and repairs the damage we do, quite effectively. Yet, today, given the scale of destruction we have wreaked on SGNP, clearly the forest needs a helping hand to survive the socio-political forces ranged against it.

Nothing I write can truly convey the sheer beauty and exhilaration that envelops anyone who enters the park’s confines. The quality of air alone, within a 500 m. walk from the bustling Western Express Highway, is dramatically refreshing.

Without exaggeration, if SGNP dies, the city itself will start dying. And with potential climate change impacts looming large, this park, together with Tungareshwar and Tansa, are Mumbai’s insurance policy against possible evacuation at the hands of extreme weather events that could trigger severe water shortages on the one hand and floods on the other.

Keeping the park safe for leopards, butterflies, spiders and birds… amounts to securing our own ecological and financial future. If this one realisation dawns on us, the park will continue to offer us its substantial ecological services, at virtually no cost apart from our appreciation.

………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Returning peace to paradise

SGNP will always be the true love of my life. SGNP was on our picnic map once a year and I remember our annual trips as “expeditions” into the wilderness. This is where I learnt the basics about birds and this is where I fell in love with nature.

It was, therefore, horrifying that in a national park located in Mumbai, there was no attempt being made to protect this paradise from illegal quarries, factories, shops, encroachments and more. The late Humayun Abdulali, stalwart-naturalist, literally gave his life in the defense of SGNP. He was single-handedly able to stop a road cutting through the national park, and also prevented a major radar installation from coming up in the core of the park at High Point. However, after he was assaulted inside the park, his brain was damaged, and he could fight no more. Such is the price people have paid to protect our wildernesses.

I stepped into the battle in 1995 when I filed a Public Interest Litigation against all illegal activities in the park. The result was that illegal quarries were shut down. The MAFCO meat factory, owned and operated by the Maharashtra Government was closed and 60 acres of forest land returned to the park. A staggering 50,000 encroachments were removed and within a short time, there was a dramatic improvement in the biodiversity of this park, and the quality of the two lakes that supply drinking water to Mumbai.

It took 17 years of my life… and it was worth every minute.

I was at Gaumukh, above the Kanheri caves, in the core zone of the park, when an illegal three-storeyed ashram, was being demolished. Somehow, that cathartic event underscored the irony of building cement temples while destroying the real temple… the forest.

None of this would have been possible without the battery of selfless lawyers who helped fight this epic battle in the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court. Credit is also due to the brave officials of the Maharashtra Forest Department who worked diligently to restore peace to paradise.

By Debi Goenka, Conservation Action Trust

………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Sanjay Gandhi National Park History

The history of SGNP dates back to the 4th century B.C., when Sopara (now Nalasopara) and Kalyan, two ports near Mumbai, were regularly used to trade with Greece and the Middle East. One of the trade routes connecting other trade centres with these ports passed through this forest. The ancient Buddhist caves (Kanheri caves) served as rest houses for traders and travellers. The word Kanheri has originated from the Sanskrit word Krishnagiri meaning ‘Black Mountain’, probably because of the volcanic landscape, formed 45 to 60 million years ago.

Before 1808, the forests of Yeoor and Nagla situated at the northern limit of the park constituted the state property under the Maratha Empire. It was only in 1945 that the forest (20.26 sq. km.) was brought under proper management and christened as the Krishnagiri National Park. In 1969, the park boundary was extended and the park given a new name, ‘Borivali National Park‘, with a total area of approximately 103 sq. km. This was subsequently renamed as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park in the early eighties.

Look Out For:

Freshwater Crab. Photo: Dr. Anish Andheria

Flora: Karanj, jambul, vat, ain, haldu, kandol, shirish, pangara, kaate saavar, bartondi, tivar, pandhra kuda, karvi, karunda, murud sheng and govindphal.

Birds: Grey Junglefowl, Indian Grey Hornbill, Indian Peafowl, Black-hooded Oriole, Blackrumped Flameback, Asian Paradise Flycatcher, Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, Black-naped Monarch, Brown-headed Barbet, Yellow-footed Green Pigeon, Crested Serpent Eagle, Changeable Hawk Eagle, Puff-throated Babbler, Jungle Owlet and Eurasian Eagle-owl.

Reptiles: Bamboo pit viper, spectacled cobra, Indian rat snake, Asian rock python, checkered keelback, common vine snake, Russell’s viper, common cat snake, common wolf snake, Indian chameleon, common Indian monitor, marsh crocodile, forest calotes, rock gecko, dwarf gecko and forest spotted gecko.

Mammals: Leopard, sambar, chital, barking deer, rusty spotted cat, hyena, common palm civet, small Indian civet, Indian crested porcupine, Indian hare, Indian flying fox, common langur and bonnet macaque.

This article was first published in the book ‘Wild Maharashtra’, a Sanctuary publication.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the Author: President of the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT), which is involved in projects across central India, Dr. Anish Andheria’s focus research area has been predator-prey relationships. An accomplished naturalist and wildlife photographer, he has authored several scientific papers and books.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

- Creatures Great And Small

- Why India Needs Stronger Laws to Protect Exotic Species on its Soil

- Making Room for Leopards

- In Hostile Territory

- Just Shush! Sincerely, Wildlife

- Plastic Runs Deep

- Thane-Ghodbunder Road expansion: Wildlife board sets up panel to find ways to reduce impact on SGNP