You won’t know when. You won’t know where. You must keep your peripheral vision peeled and neck rotating 180 degrees perpetually, for a split-second sighting along the river as it breaks the surface for air. That is the only way to catch a fleeting glimpse of the Ganges river dolphin. Each time I manage to see a dolphin, I try to make quick mental notes of the different features that I was able to register. It’s gone even before I can utter its name.

A Ganges river dolphin seen jumping out of water in the Ganga river. ©Soumen Bakshi/WCT

“How do you photograph this animal? Let alone study it!”, I ask Dr. Nachiket Kelkar sitting in front of me on the boat, cross-legged, logging the dolphin observations. Dr. Kelkar heads the Riverine Ecosystems and Livelihoods (REAL) programme at the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT). He, along with Subhasis Dey, a riverine conservationist, has been studying this aquatic mammal, its ecology, and interactions with fisheries in the Gangetic Plains for over two decades.

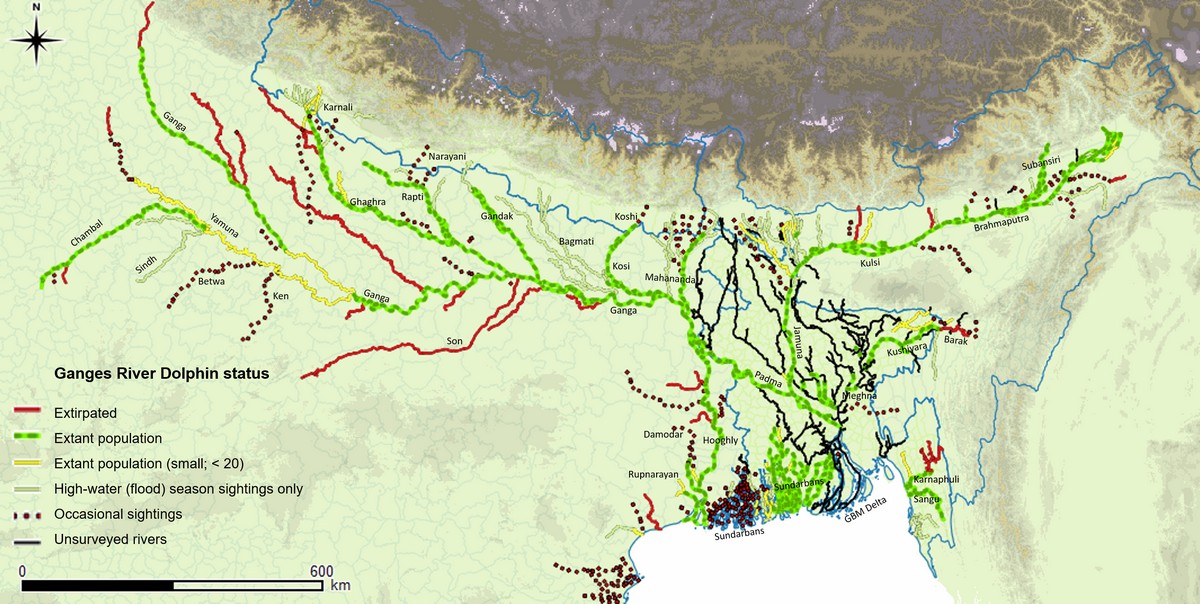

Map depicting the latest status and distribution of the Ganges river dolphin in India’s Gangetic Plains. © Nachiket Kelkar/IUCN Red List Assessment.

In India’s Gangetic Plains, accidental deaths due to fishing nets is one of the primary threats to these cetaceans. Several river dolphins die each year from getting entangled in fishing nets as bycatch. Large-meshed gillnets made from nylon and polythene monofilament are particularly dangerous for them. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List, the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica) is listed as Endangered with its total population estimated to be around 5,200 individuals across its range countries – India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, as of 2022. Studies estimate that the annual count of Ganges river dolphin deaths in fishing nets may be nearly four to five percent of their global population.

“This rate is greater than the estimated Potential Biological Removal threshold for the species,” says Dr. Kelkar.

A Ganges river dolphin accidently caught in gillnet. ©Soumen Bakshi/WCT

Ganges river dolphins echolocate constantly but may still not be able to detect large-meshed gillnets, leading to entanglement and eventual death. Artwork ©Soumen Bakshi/WCT

“Globally, bycatch mortality from entanglement in fishing gears such as gillnets has been one of the major drivers of recent or imminent cetacean extinctions such as that of Vaquita (Phocoena sinus), found in northern Gulf of California and Mexico. Only around 10 vaquita individuals, it is believed, are left in the wild. Fishing methods such as electric rolling hooks in the Yangtze River in China were responsible for the extinction of the Chinese river dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) or Baiji.”

A Festering Threat

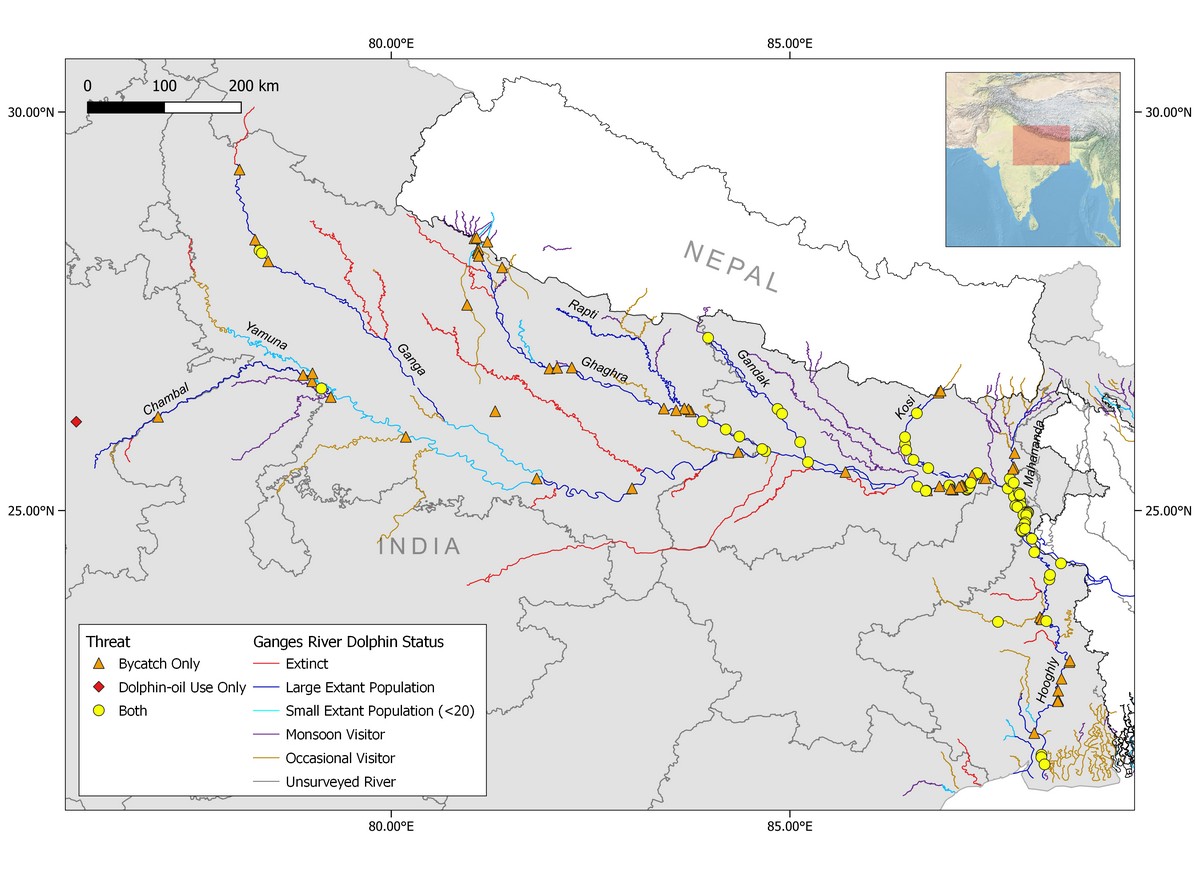

Among the threats the endangered Ganges river dolphin faces, entanglement in fishing nets is a major cause for concern, and this problem is rather nuanced and complex. Despite being accorded the highest levels of protection in India under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the dolphins caught in fishing nets are often opportunistically, and at times deliberately, killed for their oil. The oil extracted from their fat (called blubber) is commonly used as fishing bait in various parts of India and Bangladesh to catch Clupisoma garua, a species of catfish widely found in the larger, perennial rivers of the subcontinent.

The Ganges river dolphins are often illegally exploited for their oil which is used as bait for catching Clupisoma garua, a species of catfish found in Gangetic plain rivers. ©/WCT

Traditionally, different types of oil-baits, such as fish-based oils have been used to fish in the Gangetic plains by many fishing communities in parts of Bihar, West Bengal, and Assam. The practice of using dolphin oil specifically to bait Clupisoma garua could have evolved from fishers’ observations of Clupisoma fish gathering to feed on dolphin carcasses. The volatile chemicals from dolphin fat could be attracting these fish. Dolphin oil is also often used as a traditional alternative treatment for joint pains, burns, and other ailments, in the region.

The illegality involved in salvaging dolphins caught in nets for their oil, blubber, and flesh has not discouraged fishers from continuing to do so. Dolphin oil can still be obtained by fishers through regional and informal trade networks and is rampantly traded in black markets.

A Ganges river dolphin poached for its oil in the Kosi river in 2023. The carcass was hung in the open in full public view. ©Subhasis Dey/WCT.

“Fishers continuing the practice despite knowing that it is illegal, may do so as a cultural entitlement or habit, or in sheer defiance and disregard of wildlife laws. Opportunistic utilisation of the dolphins may appear occasional, but cumulatively can be a serious threat to dolphin persistence,” says Dr. Kelkar.

For Ganges river dolphins, the threats of entanglement in fishing nets and opportunistic exploitation are particularly severe in West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, and Jharkhand. Long-term monitoring of river dolphin deaths and poaching in the Gangetic plains by WCT and Human & Environment Alliance League (HEAL) reveals major poaching hotspots between the Kosi-Ganga floodplain of eastern Bihar and the Malda-Murshidabad districts in West Bengal.

A map showing relative occurrence of bycatch and dolphin oil use across the Gangetic plains in India, prepared from WCT’s informer reports, publications, and media reports. ©S. Ramya Roopa/WCT.

But why do fishers continue to defy law and risk being penalised, and avoid reporting bycatch incidents altogether?

“On the one hand, fishers largely avoid reporting accidental bycatch cases fearing legal hassles, as accidental and targeted killing are both treated as hunting and penalised in the same way under India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Most fishers in the Gangetic Plains belong to poor and socially marginalised groups and cannot afford the costs of penalties or other restrictions when accidental entanglement of dolphins happens,” Dr. Kelkar explains. “Since it invites strong penalties, even if a dolphin gets accidentally entangled, the first response of fishers is to bury or sink the carcass to avoid getting caught. On the other hand, the high value of dolphin oil in the illegal trade lures them to partake in it. Occasionally, dolphin meat is also consumed or sold off to fishers and traders, in some areas.”

Devising novel anti-poaching methods for Ganges river Dolphin

Weak law enforcement and monitoring, and the difficulties faced in collecting evidence due to costly and time-intensive molecular analyses are major roadblocks in combatting the poaching of river dolphins. Simpler, low-cost detection methods are, therefore, the need of the hour.

This enforcement lacuna is exactly what Dr. Kelkar and his team are working to address. Over the past few years, they have developed some novel anti-poaching approaches and methods (see box below) to detect, prevent, and minimise illegal use and trade of Ganges river dolphin. These methods have the potential to greatly improve initial field investigations and monitoring by state forest departments and other enforcement agencies.

“Our motivation behind the application of all these approaches is that in the short term, regular monitoring and the risk of actual conviction could serve as a strong deterrent to fishers. Continued deterrence and systematic discouragement in the long-term along with incentives, can help the fishers fully abandon illegal practices and gradually give up the use of river dolphin oil. In addition, preventing the risk of bycatch can save fishers from getting into trouble,” says Dr. Kelkar.

Such efforts seem to be already bearing fruits, even if the larger changes needed are going to take time. In places like Panchnandapur, Malda, West Bengal, where recent arrests have been made, fishers and fish traders have become more cognisant of the risks involved and are now actively dissuading other fishers from using dolphin oil. The reporting of accidental dolphin bycatch cases has also gone up with more local fishers coming forward to report them to range forest officers, sometimes with evidence such as photographs.

Developments like this fill me with hope about us overcoming the complexities involved in co-existing with wildlife and conserving threatened species like the river dolphin. As I go back to observing the dolphins splashing around our boat, another graceful leap of a brownish grey-pink individual of this relict species coming up for air signals an emphatic sign of the positive changes to come.

Some anti-poaching methods developed by WCT:

I) Visual test to detect dolphin oil use

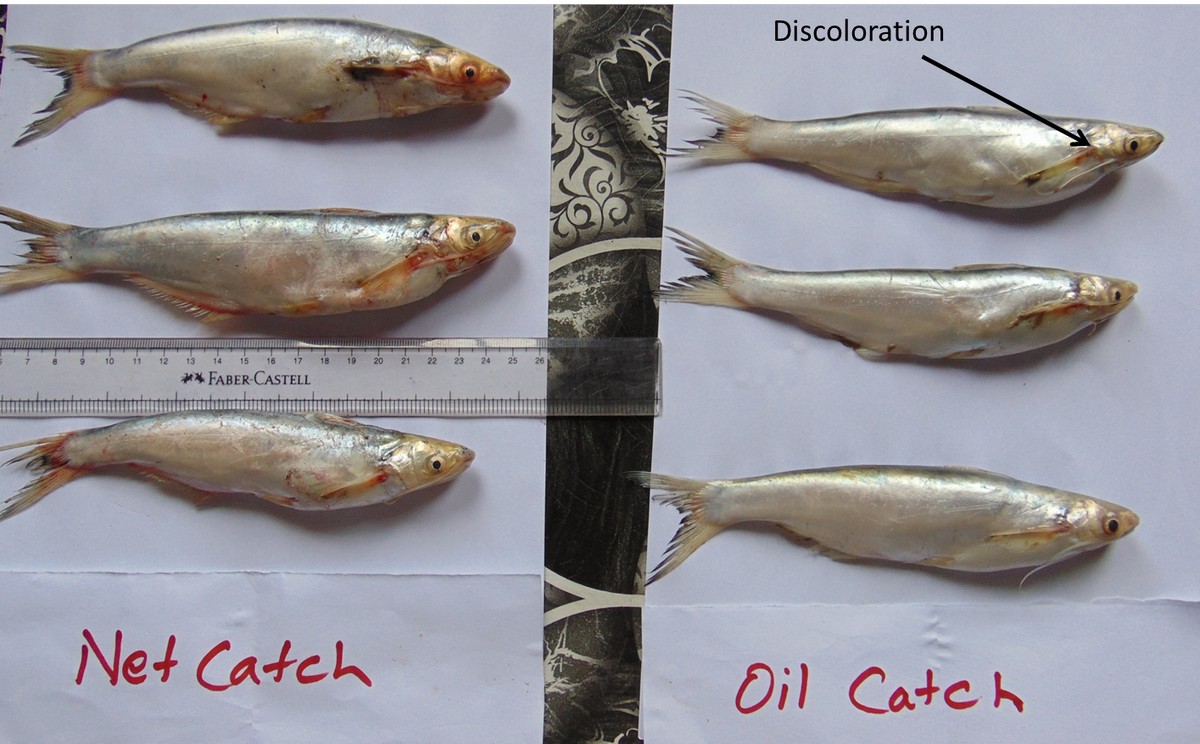

In a breakthrough study that was published in July of this year in the Whaling Commission’s Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, Dr. Kelkar and Dey presented a new visual test that relies on the differences in colour and condition of dolphin oil-baited catfish catches and net-caught catches of Clupisoma garua. While the Clupisoma captured using dolphin oil appeared discoloured and paler, the unbaited Clupisoma retained their colours. Though fishers could catch more fish using dolphin oil, the catches would putrefy faster and sell at lower prices. This new detection system, now tried and tested, can be easily implemented by monitoring agencies such as state or district level wildlife and fisheries departments.

Differences in the appearance of Clupisoma caught in gillnets (left) and those caught with dolphin oil (right). Apart from the latter being paler and discoloured, net catches appear redder and have intact natural colouration. ©Subhasis Dey/WCT

II) Cost-effective chemical tests to indicate the dolphin oil presence

The REAL team is exploring the application of chemical tests to detect differences in the chemical composition of dolphin oil and distinguish it from fish and plant oils that are also used in fishing. Analyses involving Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) tests are being tried out to develop effective kits. These tests can save significant time and money, and serve to narrow down confirmatory investigations, thus potentially aiding in an improved conviction rate. The results also indicate that other oil baits used in fishing (e.g. carp oil, shark oil, and plant-based oils like dalda) and promoted as alternatives are characteristically different in chemical composition from dolphin oil.

III) Deploying Conservation Dogs to detect dolphin oil

The sharp olfactory senses of WCT’s conservation dogs Impi, Ace, and Hira, are being honed by the team to detect Ganges river dolphin oil. The dogs are able to sniff out trace amounts of oil. The efficiency of detection and the conviction rates for poaching cases involving Ganges river dolphins could be drastically improved by similarly training forest departments’ dog squads.

WCT’s conservation dog Impi and his handler demonstrating the dog’s dolphin oil detection skills at a training workshop for the West Bengal Forest Department. ©Allen Jacob/WCT

IV) GPS and geo-fencing technology to track fishing boats and prevent dolphin bycatch

Prevention is better than cure. Since the overlapping of fishing activity and dolphin habitat leads to accidental bycatch of river dolphins, WCT has developed an innovative technological solution to minimise this overlap and thereby prevent the risk of dolphin entanglement in fishing nets. WCT’s researchers developed boatBAITS (Boat-based Buzzer Alarm Indicator and Tracking System), a buzzer device and tracking system that uses GPS and geo-fencing technology, which can be used to tag boats and track them remotely. The system is novel in that, if a tagged boat enters a “virtually fenced” dolphin hotspot, the fisher receives an alert suggesting that they move out of the area. This is a measure that involves fishers proactively staying clear of the problem of accidental bycatch.

A boat tagged with the BoatBAITS buzzer and tracking device. The boat movements can be tracked remotely using an online software system. ©WCT

“In and around aquatic protected areas, where fishing activity occurs alongside threatened riverine wildlife, the application of such a system can help to achieve effective conservation outcomes by regulating fishing boat movement, and thereby allowing better fisheries management in conservation areas”, points out Dr. Kelkar. BoatBAITS devices are set to be deployed soon on a pilot basis in the Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary in Bhagalpur, Bihar. Once implemented, this will be the first digital boat-tracking system for any riverine protected area in India.

This article was originally published in Sanctuary Asia October 2024 issue.

About the author:

Purva Variyar is a wildlife conservationist, science writer and editor, and heads WCT’s Communications vertical. She has previously worked with the Sanctuary Nature Foundation, and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

Related Links

- River Animals and River People: For a Shared Future

- A Walk to Remember: The Fishers’ Foot Migration

- WCT’s Dr. Nachiket Kelkar Honoured with NDTV True Legend (Environment) Award

- Using ‘Moths’ to Hear Dolphins

- IUCN’s latest Red List Assessment of the Ganges river dolphin