Ganges river dolphins are never quiet. They are effectively blind and do not need eyesight to live in the super-murky, sediment-rich waters of their riverine habitat. But this means that they must echolocate almost constantly to map their environment and navigate, feed, rest, and respond to environmental signals. A river dolphin produces echolocation clicks non-stop to survive in the generally tranquil, but now increasingly noisy river waters. It is next to impossible to see a dolphin underwater – the only glimpses possible last for all of 1 or 2 seconds when it breaks the water surface to breathe. So how can we learn more about its behaviour underwater? Tracking its clicking sounds is one way to go about it. This is vital to understand its behaviour and sensory environment.

In the course of evolution, the Ganges river dolphins have lost their eyesight almost entirely, since the freshwater river habitats in which they live in have very low visibility due to high sediment content. Instead, they emit ultrasonic sounds which bounce off objects around them, including live prey, helping them ‘see with their ears’ and navigate the murky waters. ©Soumen Bakshi/WCT

Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) with the use of underwater acoustic recorders and loggers has been used worldwide to study cetaceans. A wealth of information can be divined from them, in terms of behaviour, occurrence at particular sites, and movements of dolphins in specific areas. Recording dolphin sounds can offer us fascinating insights into these aquatic mammals’ feeding behaviour, social interactions and calls, as well as responses to human-made noise in the water from ships, engineering activities, mining, and whatnot.

Ganges river dolphins only produce clicks, which are simple emissions of sound, and yet can be quite interesting to study. Their high-frequency ultrasonic clicks range from 15-20 kilohertz (kHz) all the way to 200 kHz, with the maximum intensity at 65-70 kHz. Humans can potentially hear frequencies ranging between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz, however in regular life, our hearing is mostly contained between a few hundred Hertz and around 10-12 kHz, and as would be obvious, the frequencies we emit also fall in a similar range.

Listen to how Ganges river dolphins navigate using ultrasonic clicks underwater, in this audio clip. ©WCT

There have been remarkable technological advancements in the field of passive acoustic monitoring to track dolphins acoustically. One really useful and excellent device is the CPOD or the Chelonian and Porpoise Detection (CPOD, www.chelonia.ac.uk), which also provides software to directly decode, classify, and extract cetacean clicks or calls in files with analysable data. However, most such devices are quite hard to deploy underwater, require a lot of physical strength to moor, and have elaborate procedures to set up and extract data from. Not only that, high-precision underwater devices can be quite costly too.

Hydromoths being deployed in a river to detect and record ultrasonic soundwaves produced by the dolphins. ©Vedant Barje/WCT

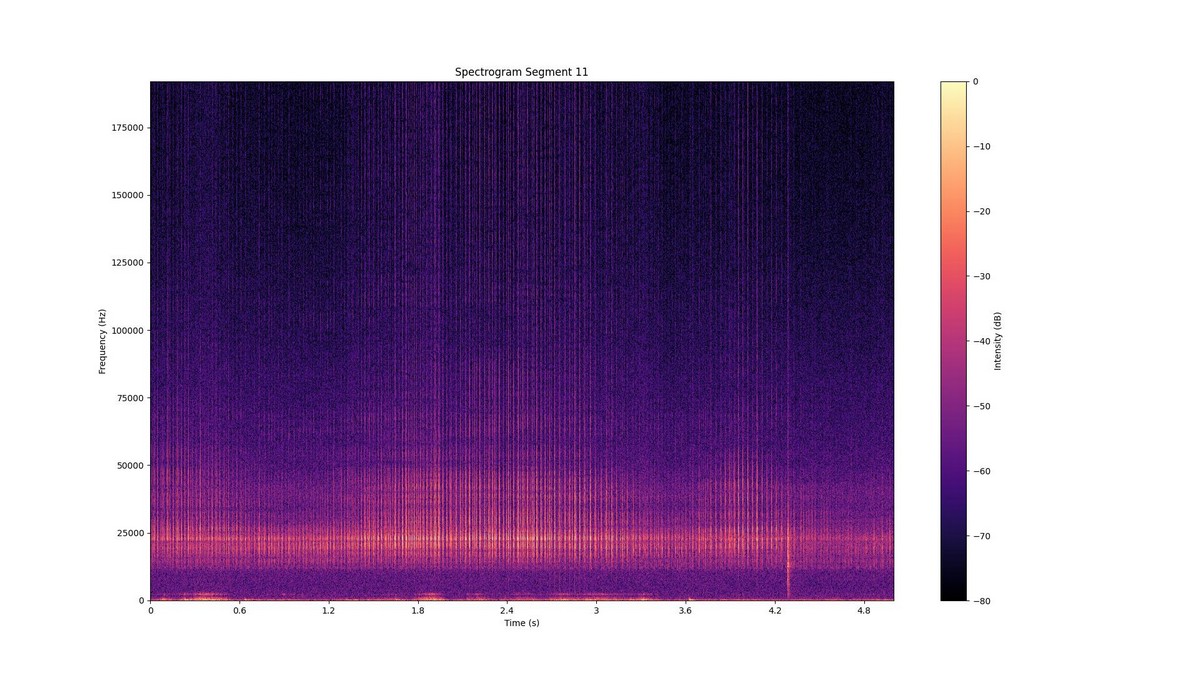

HydroMoths (https://www.openacousticdevices.info/audiomoth), developed by Open Acoustic Devices, are sibling devices of AudioMoths – which are used more widely in terrestrial wildlife monitoring – especially to study vocalisations in birds and bats. HydroMoths can be deployed for just 10 percent of the cost of conventional marine mammal hydrophones and PAM loggers, and with much greater ease, and also can be customised for start and end times of recording, sampling rate, and other parameters. The acoustic recording is interpreted by researchers by plotting it on a spectrogram, which is a graphical representation of the spectrum of frequencies of click signals as they vary in time.

The soundwaves produced by the dolphins can be seen as bright orange vertical lines in this spectrogram. Their high-frequency ultrasonic clicks range from 15-20 kHz all the way to 200 kHz, with the maximum energy at 65-70 kHz. ©WCT

Of course there are some limitations, such as the smaller area in which Hydromoths can record dolphin presence. But when the focus is on studying fine-scale behaviour of elusive species such as Ganges river dolphin, Hydromoth devices are ideal.

WCT’s REAL programme team members recording Ganges river dolphin sounds using Hydromoths in West Bengal. ©Purva Variyar/WCT

As part of WCT’s Riverine Ecosystems and Livelihoods (REAL) programme and WildTech project, we are now monitoring Ganges river dolphins with the use of HydroMoths. To our knowledge, this is the first time that HydroMoths are being used in India to study dolphins!

About the author: Dr. Nachiket Kelkar is a riverine ecologist and conservationist and heads WCT’s Riverine Ecosystem And Livelihoods (REAL) programme.

Disclaimer: The authors are associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

Related Links

- Seeing The Sounds of Nature

- IUCN’s latest Red List Assessment of the Ganges river dolphin

- Just Shush! Sincerely, Wildlife

- River Animals and River People: For a Shared Future

- A Walk to Remember: The Fishers’ Foot Migration