At the heart of a multitude of Wildlife Conservation Trust’s (WCT’s) projects lies science. Science drives and underscores the organisation’s approach to its broad and diverse range of conservation work, be it research, capacity building, conflict mitigation or advocacy.

Photo credit: Dr. Anish Andheria

My curiosity is happily piqued at the mention of science and I was eager to peek behind the curtain. As I began to probe and dissect some of WCT’s exciting work ranging from monitoring of tigers outside Protected Areas, to building capacity of the forest staff, to developing AI models to predict human-wildlife conflict , among others, quite a few interesting scientific methods were revealed to me.

Let’s take a look at some of them.

1. Profiling prey base of tigers by analysing undigested hairs found in tiger poop

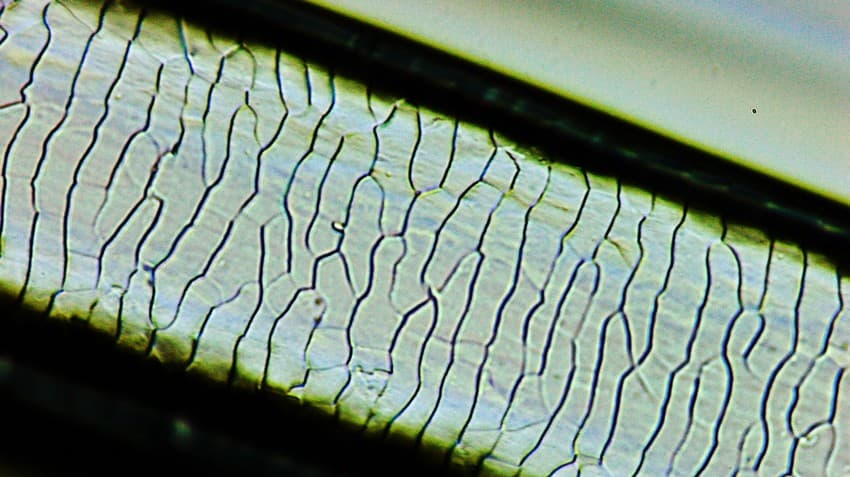

It is amazing how much information one can glean from animal poop! WCT’s tiger biologists take tiger scat (faeces) very seriously. One of the ways in which they identify the prey species that tigers feed on is by closely observing the structural characteristics of undigested hairs obtained from scat samples, under a microscope. The cuticle, or the outer layer on every strand of hair is composed of a large number of overlapping scales. Interestingly, the shape, size, margin, and arrangement of scales along the length of the hair vary across species and act as excellent clues to understanding which, how many, and what percentage of prey species make up the tiger’s diet.

Tiger scat recorded outside a Protected Area (above) and an undigested hair of prey found in scat observed under a microscope (below). Photo credits: WCT

Identifying hairs found in carnivore scat is a relatively simpler, faster, and an inexpensive way of profiling the prey base of carnivores. And tiger scat analysis is helping WCT’s scientists to find definitive answers to questions about the diet of the Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) living outside Protected Areas in Central India. This information is critical to planning conservation, protection, and conflict mitigation strategies. Tiger scat analysis is crucial to WCT’s Large Carnivore Monitoring Project, which is being carried out in collaboration with the Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh Forest Departments.

2. Using dogs’ supreme sense of smell to track Indian pangolins

In a grim paradox of sorts, despite being the most trafficked mammals in the world, we know very little about the behaviour and habitat preferences of the highly elusive and shy pangolins. WCT has embarked on an ambitious project to develop an ecology-based conservation strategy for the Indian Pangolin (Manis crassicaudata). For this, WCT’s scientists have enlisted the help of four-legged members of the team – dogs! WCT’s Conservation Dogs Unit (CDU) comprises, at the moment, four specially trained working dogs whose olfactory capabilities are aiding in ongoing conservation efforts and investigation, and a well-trained staff which works in tandem with these extraordinary dogs. The dogs can detect the presence of a wide range of target animal species, including Indian pangolins, by their scats, tracks, and urine which in turn helps to arrive at answers to research queries, conservation challenges and crime investigation.

For the pangolin project, dogs are assisting researchers in surveying pangolin habitat in Pench and Satpura Tiger Reserves in Madhya Pradesh and have been crucial in detecting the presence of pangolin. This is helping to gather crucial data for establishing robust patrolling and anti-poaching strategies with the Forest Department in critical pangolin habitats.

WCT’s conservation dog, Moya, with Prasad Gaidhani, Unit’s canine handler and researcher holding up pangolin scat that Moya helped to detect. Photo credit: WCT

3. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to predict human-wildlife conflict

Human-wildlife conflict is a major conservation challenge in India, which is intensifying in many parts of the country incurring heavy losses for people and wildlife. WCT’s Conservation Behaviour team has been applying AI in several conservation projects. One such project, which is a promising collaboration between WCT and Google Research India’s AI Lab, involves designing AI models that will help predict human-wildlife interactions in the state of Maharashtra.

Bramhapuri Forest Division in Chandrapur, is a major tiger bearing landscape with heavy tiger and human population densities. A human-dominated landscape with high densities of carnivores and reasonable populations of herbivores generates scope for humans and wildlife to interact. These interactions may often result in conflict leading to loss of farm produce and livestock and in some cases, human life. The frequency of these interactions is high as well as difficult to monitor. Understanding the various aspects of these interactions is crucial in order to identify patterns that would enable creation of strategies as well as policies to better manage and mitigate this interface.

The aim of this AI project is thus, understanding, identifying and predicting the conditions under which interactions between humans and wildlife may transform into conflict, and using these predictions to develop a policy-based solution that involves multiple stakeholders at the community, district and state levels. AI is being used to identify drivers of conflict between animals and villagers and using the predicted conflict as an input for designing an optimal policy.

4. Underwater video cameras to identify fishes

A part of WCT’s Otter Ecology study in the Satpura Tiger Reserve involves looking at the otters’ diet. This is primarily done by analysing their faeces (spraints). Otter spraint largely consists of the the remains of crabs and fish bones.

A camera trap image of an Eurasian otter in Satpura. Photo credit: WCT

Though identification of fish species using undigested bones is possible, a reference checklist of fish is required to be able to do so. To compose such a baseline list of fish species found in the freshwater streams of the Satpura Tiger Reserve, WCT’s conservation biologists survey these streams to record fish presence and diversity using underwater video cameras.

Fish presence and diversity in freshwater streams are recorded using underwater video cameras. Photo credit: WCT

This helps to identify the prey species of the otters in the river systems. The project focuses on understanding the forest hydrology in the Satpura Tiger Resreve and studying the rare Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) as an indicator species of the aquatic habitats in this landscape. The WCT team had documented the first ever evidence of the presence of the Eurasian otter in the Central Indian Landscape in 2016 through extensive camera-trapping efforts. Eurasian otters are among the rarest mammals in India and are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

About the author: Purva Variyar is a conservationist, science communicator and conservation writer. She works with the Wildlife Conservation Trust and has previously worked with Sanctuary Nature Foundation and The Gerry Martin Project.

Disclaimer: The author is associated with Wildlife Conservation Trust. The views and opinions expressed in the article are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Wildlife Conservation Trust.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Your donations support our on-ground operations, helping us meet our conservation goals.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Related Links

-

[Expert Speak] Decoding the Hunting Strategy of a Cat That Fishes

-

Meet 12 Incredible Conservation Heroes Saving Our Wildlife From Extinction